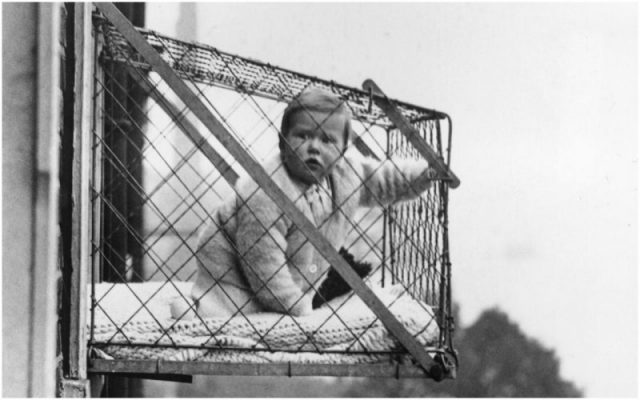

Fresh air is good for everyone’s health, especially kids. That’s accepted conventional wisdom today. Just look at all the babies being paraded around in high-end strollers and baby backpacks. But it was a radical notion at the turn of the last century, as were some of the ideas of how to get fresh air. In a move that was either ingenious or insane, depending on your point of view, some mothers living in urban tenements gave their offspring the necessary outdoor time by putting them on platforms attached to windowsills–in a baby cage.

Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, often cited as the father of pediatrics, was an early proponent of “baby airing.” The director of New York’s Babies Hospital in the late 1880s, he had wide influence in the care of infants. His observations of infant mortality rates in tenements from high bacteria levels led to the creation of milk certification. During his hospital rounds, he noticed that nurses were attaching clipboards to infants’ cribs in order to keep track of medications and progress. He began jotting his own notes, thus giving birth to the “medical chart” still in practice today. He collected notes from his own observations and those of the nurses with whom he worked to write the seminal child-rearing text, The Care and Feeding of Children: A Catechism for the Use of Mothers and Children’s Nurses (1894).

“Fresh air is required to renew and purify the blood, and this is just as necessary for health and growth as proper food,” Dr. Holt wrote. “The appetite is improved, the digestion is better, the cheeks become red, and all signs of health are seen.”

Dr. Holt went on to say that a child could be exposed to fresh air in a baby carriage, or by sleeping out of doors, or by having his crib placed a few feet from an open window. “All the windows are then thrown wide open,” he wrote. “Screens are unnecessary.”

He believed that fresh air would boost the baby’s immunity: “It is almost invariably the case that those who sleep out of doors are stronger children and less prone to take cold than others.”

While Dr. Holt did not specifically recommend airing a baby on a fenced-in platform outside a tenement window, by the early 1900s that is exactly what some enterprising (or desperate) mothers resorted to.

And it wasn’t just the poor. Eleanor Roosevelt, who’d heard fresh air was good for babies, hung a chicken-wire cage outside her East 36th Street townhouse window in 1906 for baby Anna to nap in. The window faced north, where it was cold and shady. “I had never any interest in dolls or little children,” Roosevelt wrote in her autobiography. “And I knew absolutely nothing about handling or feeding a baby.”

Anna cried piteously in the napping cage, which alerted neighbors, who threatened to report Roosevelt to the Society of Prevention of Cruelty to Children. “This was rather a shock for me,” Roosevelt wrote. “I thought I was being a very modern mother.”

In his 1906 book The Health-Care of the Baby, author Louis Fischer describes a “Boggins Window-Crib” as a “convenient outdoor sleeping compartment readily attached to any window.”

“This outdoor crib is admirably adapted for city apartments,” Fischer wrote. “It is thirty-six inches long by twenty-four inches wide and twenty-seven inches high. … [The baby] can be kept in view of his mother or nurse. The metal roof is insulated, so that the compartment is always cool in summer. The reinforced screens make it absolutely safe. The baby can not fall out, and flies or mosquitoes can not get in.”

Fischer makes the in-window crib sound actually quite reasonable.

In 1922, an inventive young mother applied for a patent for a “portable baby cage.” In her application, Emma Read of Spokane, Washington, wrote “it is well known that a great many difficulties rise in raising and properly housing babies and small children in crowded cities, that is to say from the health viewpoint.”

Emma Read proposed to provide an “article of manufacture for babies and young children, to be suspended upon the exterior of a building adjacent an open window, wherein the baby or young child may be placed. This article of manufacture comprises a housing or cage, wherein the baby or young child together with proper toys may be placed.” Her invention looked like a chicken coop; she received her patent within a year.

The practice seems to have reached a peak in London in the 1930s, when the Chelsea Baby Club distributed baby cages around the city. In post World War II rebuilding after the Blitz, some modern architects included baby balconies in their designs of middle-class homes.

Baby cages fell out of favor in the second half of the 20th century, concurrent with rising concerns about and awareness of infant and baby safety.

Not to mention that today your baby can get fresh air comfortably perched in a $1,500 stroller—and who knows, in 100 years, some people might say that idea is insane!