On Christmas Day 1948, a small group of poorly fed chickens profoundly changed the modern world.

While few might recognize the importance of that date, chances are they’ve weighed in on the resulting debate on food cultivation that is escalating even today.

It started in a New Jersey lab, where researcher Paul Jukes had gone to feed and weigh the chickens. The young hens and roosters were being given a diet without much in the way of actual nutrition. The experimental additive was an antibiotic. Otherwise, the diet was so poor that many of the chickens in the additive-free control group had already died. For comparison, a third group was given a vitamin B12 additive already on the market.

Jukes, who had told his lab assistant to take the day off to enjoy the holiday, worked matter of factly until he started comparing the results. The chickens that received the antibiotic were significantly larger than the vitamin-fed chickens that did not.

The results were important because chickens were increasingly being raised in larger settings, rather than the free-ranging, small-farm variety that ate well and thrived on a protein-rich diet of insects, grains, and grubs they were able to scratch up.

After World War II, the demand for chicken had collapsed. Poultry producers, looking for cheaper ways to raise birds in confinement, switched from fish meal to soy beans, but their chickens responded poorly. They grew slowly and their eggs often failed to hatch.

The vitamin B12 helped, but Jukes’ company–in competition with the vitamin maker–was looking for an alternative of its own.

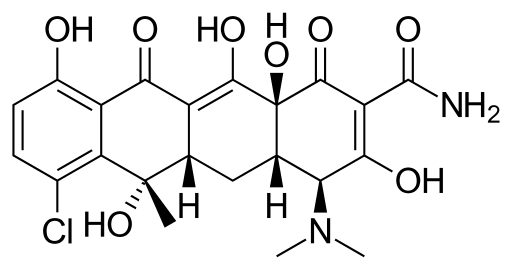

The chickens that had received the antibiotic Aureomycin were a full one-third larger than the chickens given the same diet but with vitamin B12. The results, confirmed again and again in later studies, were enough to change the face of agriculture. Jukes began passing out samples to scientists at state agricultural colleges across the country and the scope of animal tests expanded. Turkeys also grew faster. Piglets were cured of a bloody diarrhea that before would have killed them and they grew markedly faster on antibiotic-laced diets.

With cheap, antibiotic-enhanced feeds, meat producers were soon ramping up to the massive factory farms that are commonplace today.

Lederle, the company that made Aureomycin, originally registered it as a human medication, but in the agricultural world, it called the antibiotic a “food supplement.”

Farmers clamored for it, and a New York Times reporter at the 1950 meeting of the American Chemical Society wrote a front-page story trumpeting “‘Wonder Drug’ Aureomycin Found to Spur Growth 50 Percent.”

In 1956, Lederle was running print ads promoting what it called the “acronizing” process–dunking chicken in an antibiotic solution as a meat preservative. It “brings you chicken at the very peak of taste and flavor,” the company crowed.

Aureomycin was cheap, and with “no undesirable side effects,” Lederle claimed. But even several years before Jukes’ chicken experiment, the dangers of careless use of antibiotics had been noted. Nobel Prize-winning scientist Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, said in 1945 that using too little could create drug-resistant bacteria.

By 1947, drug-resistant cases involving people were showing up in London hospitals and, later, in the United States and Australia. Even so, the FDA accepted the growth-promoters’ safety claims.

Not only could farmers get by with lower-grade food using the products, they could manage with lower quality care of the animals. Animals could be packed more tightly into feedlots and barns, and their quarters could be cleaned less frequently. Their pests and parasites could be ignored.

Industrial-scale agriculture had taken hold.

Meanwhile, antibiotic resistance today is widespread and considered a looming human health threat. The use of antibiotics for animal growth was stopped in the United States in 2017, although farmers can still use them for disease treatment.

Terri Likens‘ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through The Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile, and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tenn.