The blue and gray of the Civil War had a surprising pink streak running through it.

Even though the Union and Confederacy both strictly forbade women from fighting, an estimated 400 to 750 women clandestinely took up arms for one side or the other.

Why did they go? For the same reasons that the men did. Often times, patriotism was a part of it, but some wanted a paycheck or adventure away from the life they knew. Others wanted to be closer to men in their lives who were fighting.

The women who enlisted were often from the same general demographic of the men who volunteered: they came from struggling farm families. It wasn’t that hard to hide their gender. Physical exams were not known to be rigorous and many of the women seemed no less manly than the teenage boys that enlisted. Union soldiers were supposed to be 18, but many a blind eye was turned to younger teens.

The Confederates didn’t even have an age limit.

More buxom women bound their breasts, and all wore layered and loose garments, sheared their hair short, and rubbed a bit of dirt on their faces. They kept to themselves, helping to further conceal their true identities.

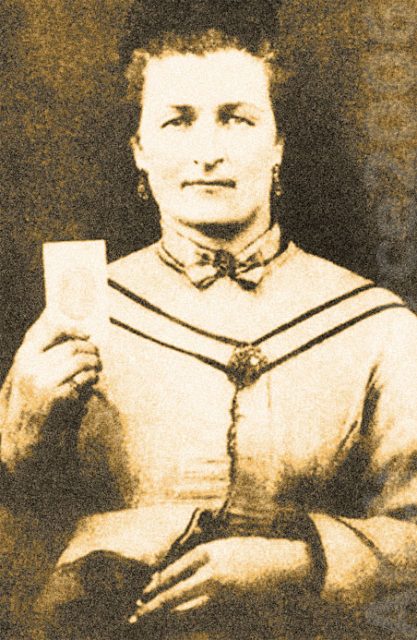

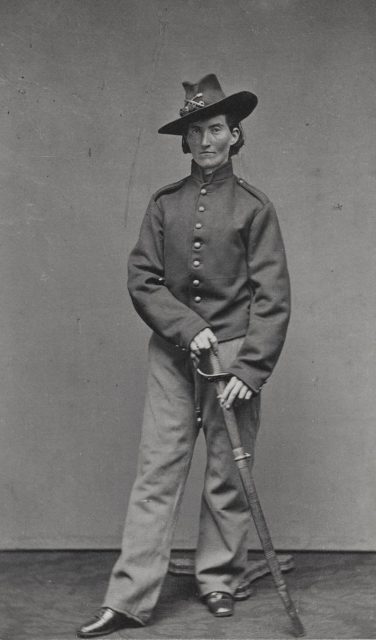

One of the best-documented cases involved Jennie Hodgers, who fought as Albert Cashier of the 95th Illinois Infantry. She participated in more than 40 engagements.

What makes her stand out from many of the others was that she continued her secret life as a man well after the war.

The resident of Belvidere, Illinois, joined the Union Army in August 1862. As Cashier, she was the shortest soldier in the regiment, but was always able to hold her own. She was in the siege of Vicksburg, the Battle of Nashville, the Red River Campaign and the battles of Kennesaw Mountain and Jonesborough, Georgia. Although details are scarce, there are also reports that she was captured and overpowered a guard to get away.

She served her full three years in a regiment that lost 289 soldiers to death and disease.

After mustering out, she went to Saunemin, Illinois, and lived out much of her life as a man. She held jobs as a farmhand, church janitor and cemetery worker. At a time when women had no right to vote, Albert Cashier did. She also collected a veteran’s pension.

In her old age, she was hit by a car and sent to the Soldiers and Sailors Home in Quincy, Illinois, as a man. However, she developed dementia and was sent on to a state hospital which discovered her female identity and forced her to wear a dress.

When the press printed the story, her former comrades rallied in her support. When she died in 1915, she was buried in full uniform under a tombstone inscribed with her Albert Cashier name and military service. Nearly 60 years later, a second tombstone was added listing her name as Jennie Hodgers.

On the Confederate side, Sarah Pritchard couldn’t stand to let her husband, Keith, go to war without her, so she cut her hair and enlisted as his young brother “Sammy.” They fought in three battles together.The jig was up when she was shot in the shoulder and sent home with Keith, who had faked an illness.

The fighting must have suited them. They later switched sides, joining a voluntary guerrilla squadron for the Union.

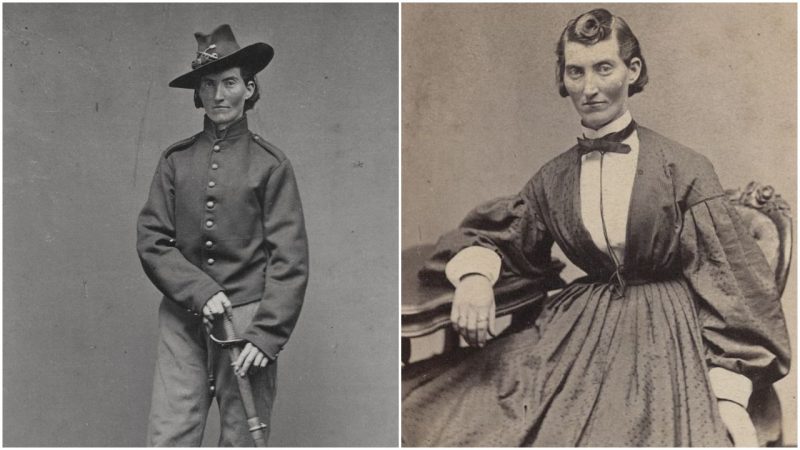

Frances Clayton was another female fighter who went to war with her husband. She and Elmer had lived on a Minnesota farm, but when he went off to fight, she took the name Jack Williams, disguised herself and joined him.

Newspapers published conflicting details, but it has been established that the two enlisted with the Union army in Missouri in 1861. The mother of three served in the artillery and cavalry corps and fought in the three-day Battle of Fort Donelson in Tennessee, where she was wounded. Even so, her gender identity remained a secret.

Sources also agree that she watched her husband die at the Battle of Stones River, also in Tennessee, and continued to fight.

Perhaps Clayton managed to continue so long because she was tall with a strong physique. Whether she intentionally allowed her true identity to be known or if was by accident is unclear. She went back to Minnesota, was able to collect some war benefits in Illinois, and after some meandering was reportedly last heard from on her way to Washington, D.C.

The Civil War was said to have moved forward another clash – women’s fight for the same rights as men. Whether as nurses on the field or holding things together at home in men’s absence, women’s strengths were able to shine through in ways they had not been seen before.

And so eventually the War Between the States came to have an impact on equality between genders, not just races.

Terri Likens’ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through The Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile, and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tennessee.