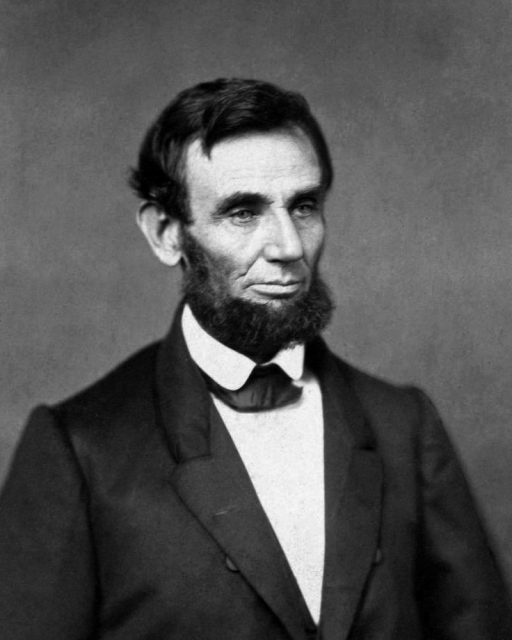

In years past, U.S. presidential inaugurations were held in March, not January. Abraham Lincoln’s was set for March 4, 1861. So, on February 11, he boarded a train in Springfield, Illinois, and set out on a tour which would ultimately end with his arrival in Washington, D.C. in time for the solemn ceremony.

However, seven days into that trip, Jefferson Davis was sworn in as the President of the Confederate States of America, and men loyal to him and to the cause that they shared were determined that Lincoln would never reach the swampy capital of the United States alive.

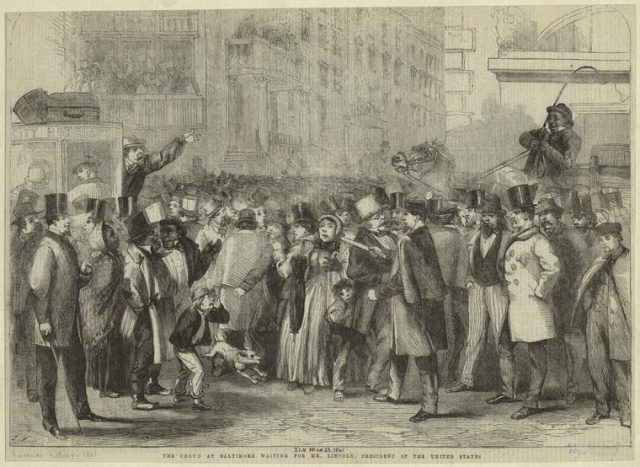

Rumors of plots against Lincoln’s life were coming in daily from all over the country: St. Louis, Chicago, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, New York, Philadelphia, and especially Baltimore, where Lincoln’s train would have to pass on its way to Washington. Maryland was a slave state. Secession was popular among its people and their politicians. In contrast to their northern neighbors, the Maryland state legislators, knowing that the President-elect was to pass through, offered no official greetings, passed no welcoming resolutions, and provided no official invitations.

Baltimore, in particular, was rife with private military organizations determined to push Maryland to secede from the Union and even prevent soldiers from reaching Washington from the north. General Charles Pomeroy Stone, the Inspector-General of Washington, the military officer in charge of all troops in the nation’s capital, employed New York City detectives to act in an undercover capacity to infiltrate not only secessionist military organizations but the Baltimore police department as well. The police chief, George P. Kane, was openly in favor of the Confederate cause. These undercover detectives reported more than one threat to assassinate Lincoln in Baltimore as the specific time of his passing through the city became known.

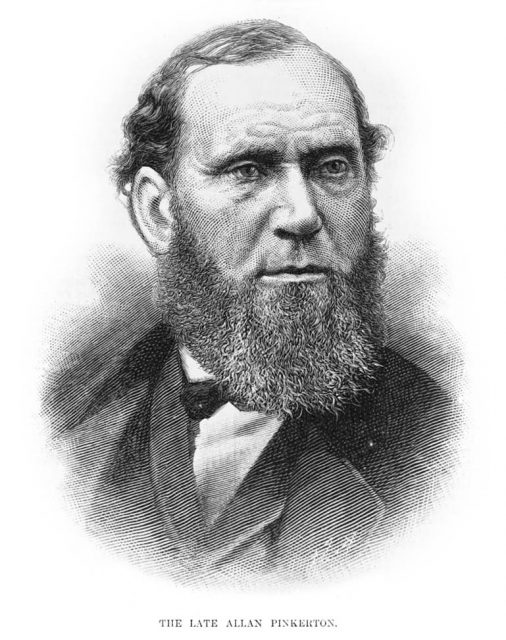

Chicago private detective Allan Pinkerton had been hired by railroad executive S. M. Felton to investigate attempts by secessionists to destroy railroad property. Pinkerton had his own operatives working incognito in Baltimore, including himself. Posing as a Georgia secessionist, he rendezvoused in a Baltimore saloon with a barber named Fernandini who had become captain of a secessionist society. Fernandini unabashedly called for the death of Abraham Lincoln and described to Pinkerton a specific plot which he had masterminded to achieve that goal.

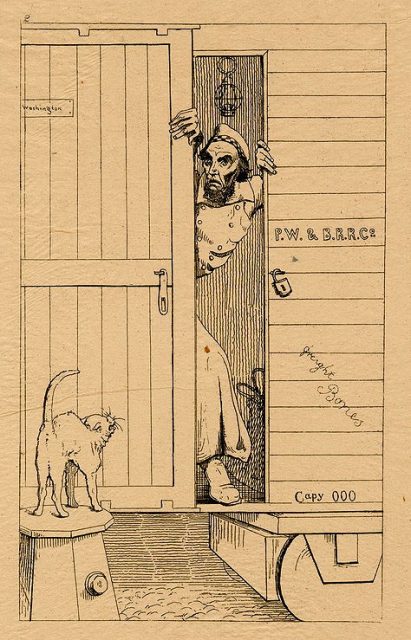

In those days, a traveler to Washington entered Baltimore on Fenton’s Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railway, but left the city on the Baltimore & Ohio. The transfer was effected by hooking the train cars to a team of horses that would haul them through city streets to the B & O station. It was during this transfer that the plan for the assassination of Lincoln would take place.

According to the plan, Kane, the police chief who was in on the plot, would send only a small contingent of his men to protect Lincoln. Some of Fernandini’s men would start a fight elsewhere to draw the police away, leaving Lincoln unprotected, at which point Fernandini and his assassins would shoot or stab the President-elect to death.

To avert this horror, Pinkerton approached one of Lincoln’s confidants, Norman B. Judd of Chicago, and secured an interview with the President-elect at his hotel, the Continental, in Philadelphia on February 21st. Pinkerton wanted Lincoln to accelerate his schedule and go to Washington that very night, on the 11 P.M. train, instead of on February 23rd, as originally planned. Lincoln refused. He was to deliver speeches in Philadelphia and Harrisburg the next day, and would raise the American flag in a ceremony at Independence Hall.

Inspector-General Stone was operating independently of Pinkerton with his own sources, and he came to the same conclusion: that Lincoln should cancel his engagements and come to Washington early and surreptitiously to thwart those conspiring to kill him. However, Stone went about his approach to Lincoln in a more indirect and ultimately more successful manner.

Instead of a personal interview with the President-elect, Stone set up a meeting with Senator William Seward, already selected as Lincoln’s nominee for Secretary of State. With a letter of introduction from the General-in-Chief of the Army, Winfield Scott, Stone outlined the impending threats against Lincoln in Baltimore and advised that Lincoln proceed through Baltimore a day earlier than scheduled. Seward, impressed with the urgency, conveyed this to his son Frederick, who met with Lincoln on February 22nd at his hotel in Harrisburg. The authority of the Sewards, Inspector-General Stone, Stone’s commander Winfield Scott, and Stone’s independent sources, which confirmed Pinkerton’s information from the night before, convinced Lincoln that he must arrive in Washington a day early and that his very life depended on it.

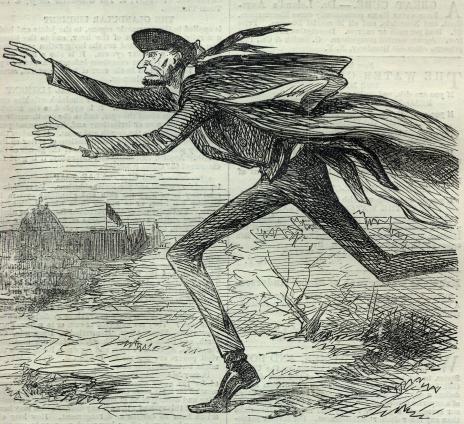

On that evening, Lincoln made two speeches in Harrisburg, greeted a large crowd in a reception at the state house and attended a banquet at the Jones House Hotel given by Governor Curtin. He left the reception early, changed clothes in his hotel room, and entered a carriage from a side door of the hotel with his friend and former law partner, Ward Hill Lamon. Lamon was armed with two pistols, two derringers, and two large knives. The carriage headed to the train station. The two men boarded a special train.

The train left Harrisburg at 6 P.M. en route to Philadelphia. As the train departed, the telegraph lines between Harrisburg and Baltimore were cut as a precaution. In Philadelphia, they were met at the depot by Pinkerton, who took them in a carriage to the P. W. & B station, where they boarded the last sleeping car of the Baltimore train. The tickets had been purchased by a Pinkerton operative in the name of her “invalid brother” and a companion.

They reached Baltimore at 3:30 in the morning. Their car was drawn through Baltimore streets to Camden Station, where it was hooked up to the train to Washington. Lincoln arrived safely in Washington at 6 A.M. at the old Washington railroad station at Second and Pennsylvania Avenue, now part of the Mall. He was greeted by Illinois congressman and political ally Elihu B. Washburne and taken to Willard’s Hotel.

And Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as the sixteenth president of the United States on Monday, March 4, 1861.

Max Eastern is the author of the noir thriller “The Gods Who Walk Among Us,” a winner of the Kindle Scout competition. To learn more, go to maxeastern.wordpress.com