Who doesn’t like to dance? It’s a great way to express yourself, have some fun, and burn some calories at the same time. Every era has different dance fads, such as the Macarena or Gangnam style.

While these fads come and go quickly, future generations tend to look back and utter, “What were they thinking?”

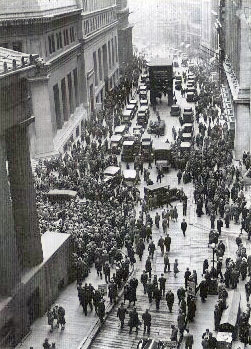

But unquestionably the hardest to fathom time was when dance took a dark turn in the 1930s, and a simple fad became a serious method of surviving one of the hardest eras in America: the Great Depression.

In the early 1920s, dance marathons became all the rage. Dance marathons, also known as walkathons, were contests of endurance in which men and women would dance for as long as they could in order to win prizes.

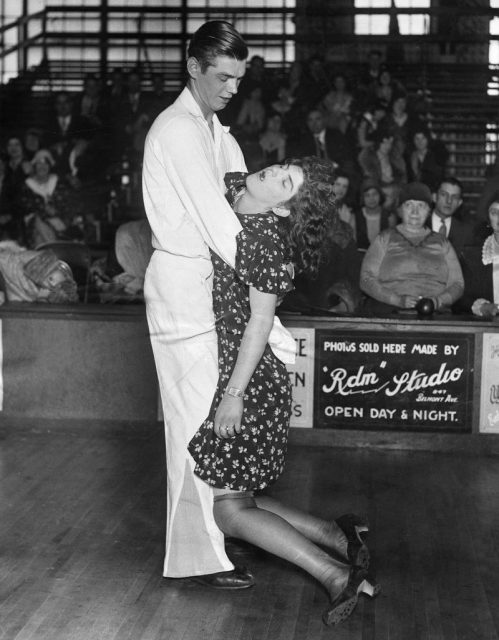

These were often grueling and exhausting affairs, with dancers staying in motion for several days (and in some cases, several weeks) just so that they could win a prize.

It was a novelty, meant to showcase an individual’s stamina for kudos and cash. The dances were often simple shuffling and moving of the arms and hips, as a means to conserve energy.

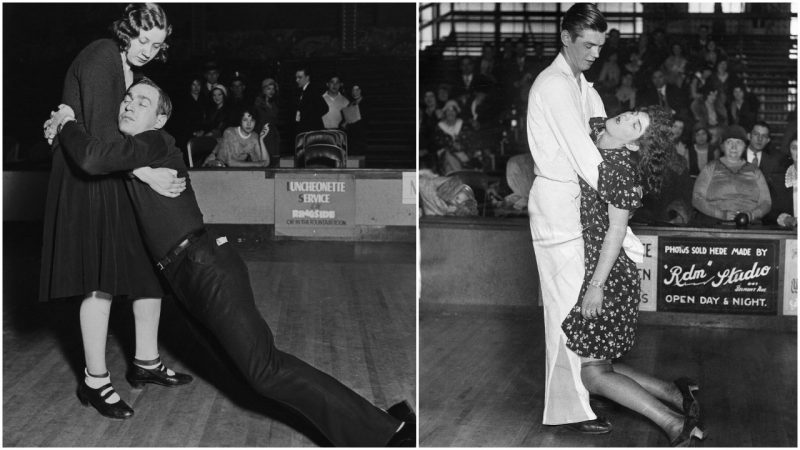

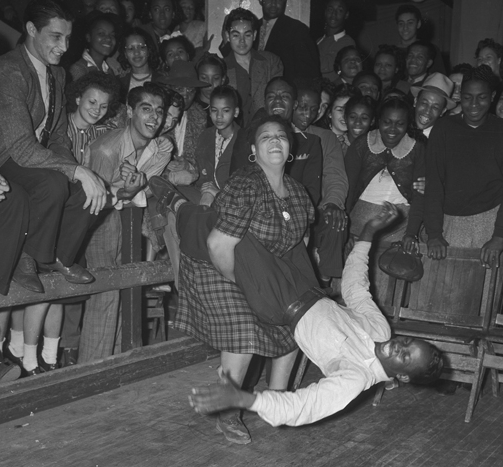

These dance marathons became a spectacle, with dancers pushing themselves to their very limits. For as little as a quarter, spectators could go and watch these competitions for as long as they wanted.

Some weren’t just there to cheer people on, rather they were hoping for a morbid show in which a dancer would collapse or even suffer from a mental breakdown.

Onlookers would often pour in, all waiting and watching with baited breath to see what kind of excitement would happen during the marathon.

As silly and needlessly exhausting as dance marathons were, they took a serious turn when the Great Depression worsened.

With a large percentage of America unemployed and unable to provide for themselves, the competitions were seen as ways to not only make money if they won, but to also be fed for the duration that they danced.

The long marathons usually had rules that a partner was allowed to take a break as long as the other one was still dancing. Some even allowed for breaks every hour.

Food was served several times a day to the dancers, but the contestants were usually required to eat while moving.

The food was provided by the dance competition host, meaning that if a person wanted to enter into a dance marathon, they would be fed. After all, these dancers were part of an income stream for the hosts, as onlookers were charged to watch the show.

Some of the best slang from the 1930s era.

Then there was the theatrics. Many of these patrons were there to watch a spectacle, not a hundred people exhaustedly shuffling along for hours at a time.

Some marathon hosts wanted to ensure that their competition would draw crowds and bring return business and so would hire individuals to take a dive during the competition.

For a fee, the diver would make a real show of passing out or having a breakdown in order to stir up the crowd. Some hosts went as far as to rig these dances, to ensure that a certain couple would win.

By throwing in a ringer, a host could see to it that the competition lasted as long as possible and even created a compelling story for the viewers who would watch these competitions from beginning to end.

Yes, these manufactured dramas were in a lot of ways reminiscent of the reality television that is so popular today.

Since dance marathons were a relatively cheap form of entertainment, those who attended frequently would begin to experience a connection with certain dancers. This would spur them on to return again and again in the hopes of seeing their favorite win.

While these marathons were a way for those beleaguered by the tolls of the Great Depression to get away from their problems for some time, the shows were not without criticism.

Many became concerned with the human rights aspect of watching people perform for days at a time, unable to sleep for more than a few minutes during breaks.

While many a hopeful individual would enter the contest for a chance to win serious money, there was most likely a professional dancer in the running, meaning the actual chance of winning for the average person was quite slim.

To undergo a grueling process, dancing for others amusement without a chance of winning, was seen by detractors as cruel.

And of course, there were opponents who had professional reasons to be critical. Theater operators often decried the morality of these dances, although in truth they were incensed not because of religious conviction but because marathons were direct competition with the movies.

Regulation began to build across the country, as incidents and pressure from special interest groups influenced local governments.

But in the end, these dance marathons would die out as a fad not because of government or group outrage, but because of an altogether different problem.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entrance into World War Two radically shifted the nation’s focus. Instead of avoiding their troubles, men took up arms and went to serve their country.

Women were left without dance partners and instead had to focus on managing their household or working in factories.

The marathon fad died swiftly, putting to end a curious and strange American pastime. While it might have looked goofy to those outside of it, these dance competitions were just another means of survival in a dark and desperate time.

Andrew Pourciaux is a novelist hailing from sunny Sarasota, Florida, where he spends the majority of his time writing and podcasting.