Nearly a century ago, the world was dazzled by the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

It was a lengthy and costly project, and there was no guarantee that British archaeologist Howard Carter, his team, and the effort’s sponsor, Lord Carnarvon, would be able to find what turned out to be one of the most spectacular archaeological gems of the century.

Fortunately, they triumphed: The grave site was traced to the Valley of the Kings, a discovery that blew everyone’s minds on November 4th, 1922.

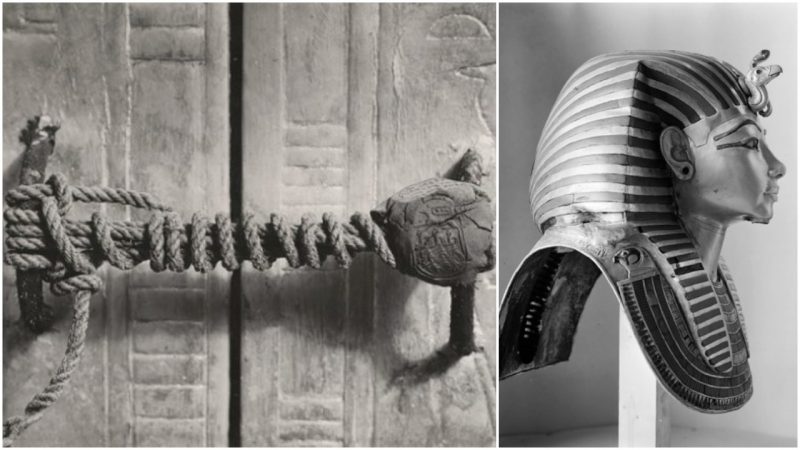

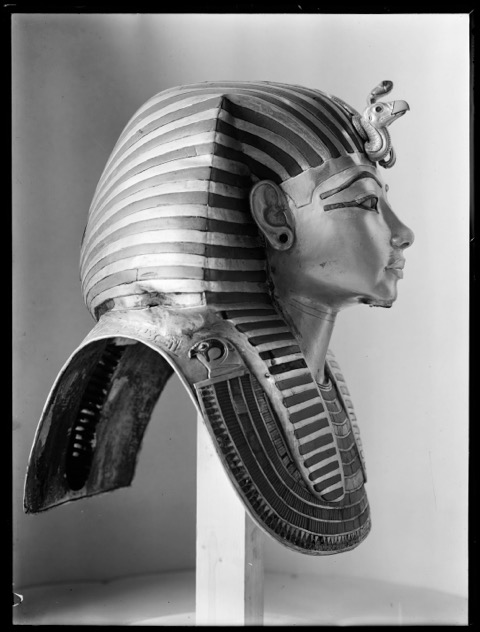

For three millennia the tomb of the great Egyptian boy pharaoh had survived undisturbed. The finding stirred up excitement that echoed through the rest of the decade and even the decades afterward.

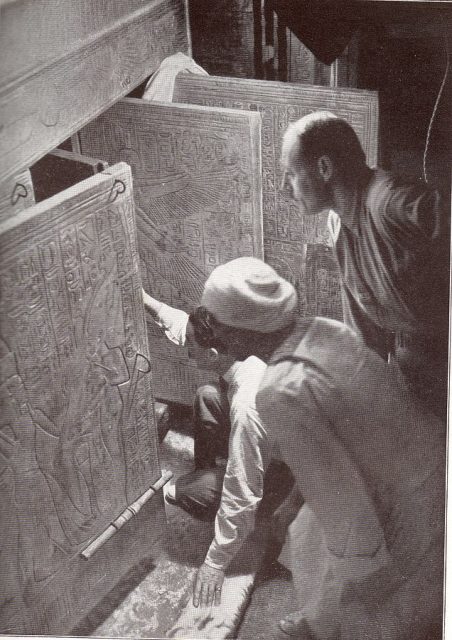

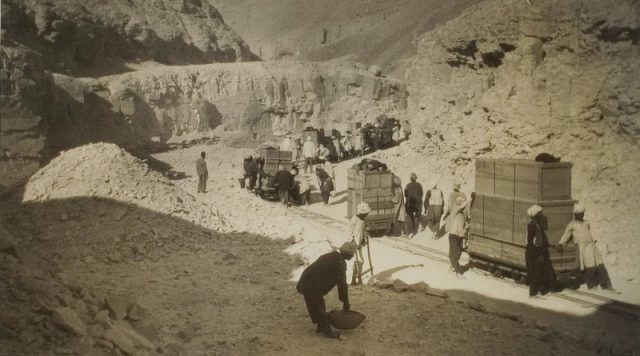

The work on the site at the Valley of Kings was uniquely documented by the camera of Harry Burton, who joined Carter’s expedition after the Egyptologist requested the services of a photographer from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Burton, who for most of his career was affiliated with the New York-based museum, accepted the assignment in Egypt. During the eight years following the tomb’s discovery, he created thousands of photographs which capture the entire excavation process. Burton took photos of the countless artifacts that were brought out of the ground, his pictures somehow capturing the atmosphere of amazement and awe at the dig site.

A fresh exhibition of his images reveals some of the historical context and meaning behind Burton’s ground-breaking archaeological photographic collection.

The exhibition is curated by Dr Christina Riggs from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and will be hosted by the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), at the University of Cambridge, in England.

Titled “Photographing Tutankhamun,” it will open at the MAA on June 14. Previously it was shown at The Collection Museum and Gallery in Lincoln, where the exhibition opened in November last year–95 years after the tomb was found.

The selection of images includes digital scans from Burton’s original glass-plate negatives, alongside newspaper reports and other publicity material that was printed throughout the 1920s, giving visitors an exciting new perspective on how the world-famous discovery was promoted to, and received by, the public. It highlights clear differences between how the proceedings were reported for the Middle Eastern audience versus English and American publications.

“The exhibition gives a fresh take on one of the most famous archaeology discoveries from the last 100 years,” says Dr. Christina Riggs in a press release statement ahead of the exhibition opening at MAA.

Disturbing occasions when ancient Egyptian curses seemed to come true

Dr. Riggs is from the School of Art, Media and American Studies at UEA, and curated the exhibition after scrutinizing 1,400 photographs authored by Burton, which are contained in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art archives.

“It questions the influence photography has on our perception and provides insight on the historical context of the discovery–a time when archaeology liked to present itself as a science that only Europeans and Americans could do,” Dr. Riggs says in a statement.

Riggs’s exhibition, which was financially supported by the British Academy, is the first of its kind to look at Burton’s work in such a context. It demonstrates how the Egyptian workforce that supported the 1920s explorations, and the vital contribution made by the government of Egypt, was under-promoted in Western media.

“This refreshing approach helps us understand what Tutankhamun meant to Egyptians in the 1920s–and poses the important question of what science looks like and who does it,” adds Dr. Riggs.

Such a context is intriguing indeed as it tackles the question of what powers photography has had on shaping our understanding of the world in the past as much as at present.

The exhibition aims to refresh perspectives. Dr. Riggs has delved deep into museum archives, where she unearthed some of Burton’s personal testimonies, impressions, and more details of the fieldwork at the ancient Egyptian site.

The excavation seems to have been thoroughly documented, from issues and internal affairs the team experienced to matters of political weight that remained hidden from the public eye.

Over two dozen images have been reproduced for the purposes of the latest exhibition, and some of the photographs have never been seen by the public before. The digital scans of Burton’s original glass-plate negatives were made by the University of Oxford’s Griffith Institute, which houses its own mountain of archive material written by Carter himself.

Senior Archaeology Curator for the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Dr. Chris Wingfield, expressed happiness that the University of Cambridge department will now have the opportunity to host this exhibition.

Related story from us: Wooden panel portraits depict the faces of Egypt of 2,000 years ago

“We continue to train Egyptologists and archaeologists here in Cambridge, so this exhibition is an opportunity to think about how these disciplines were practiced in the past, and to help shape their future,” says Dr. Wingfield.

The exhibition will be available to see in Cambridge until September 23 of this year.