The business of kidnapping is worth billions of dollars and according to CNBC “A startling 60 percent to 70 percent of overseas kidnapping goes unreported.”

This whole industry of snatching and kidnapping goes far back into history. But the sad story is that not even the dead were safe from the entire snatching business.

It was during the 19th century when this practice reached its peak. The medical schools of the day used real dead bodies to teach anatomy to the students. But in order to do so, the schools needed, and how ironic this sounds, a fresh supply of corpses. This is where the body snatching comes in.

The practice of grave robbing is ancient. The most notable example is, of course, the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was here that Pharaohs and Queens were laid to rest in their sarcophagi surrounded with amulets and gold and items that would aid them in the afterlife.

The Egyptians did everything possible to keep their dead safe. But the grave robbers were foxy and couldn’t let such an amount of gold to remain buried and forgotten. So they always came up with clever ways of how to rob the dead Egyptian royalty.

Fast forward to the 19th century and the real gold now was the dead body itself. Medical schools received the cadavers of people who were sentenced to death. But the problem was, the medical schools gained in popularity and more students enrolled.

The bodies that the court was providing weren’t sufficient. And so the demand for more dead bodies gave birth to a whole new business. “Because the only bodies legally available for medical dissection were the remains of executed criminals, demand far outpaced supply,” writes Britannica.

Centuries before this practice was born, Leonardo da Vinci himself was slicing people up, to study what was beneath all that skin. He was fascinated with the human body, and in his career, he dissected more than 30 cadavers.

“By 1508, by his own reckoning, he had conducted more than 10 human dissections. Nine years later, this tally had risen above 30. But his study of the cadaver “del vechio” (“of the old man”), as Leonardo called him, rekindled his long-held obsession with the structure of the human body,” writes The Telegraph.

Mysterious Islands From Around The World

He did this slicing-and-sketching art of his illegally. The Art Crime Archives notes that “Dissection was completely illegal unless one was a physician, which da Vinci was not.” And this happened during the 16th century, 200 years before it became mainstream practice.

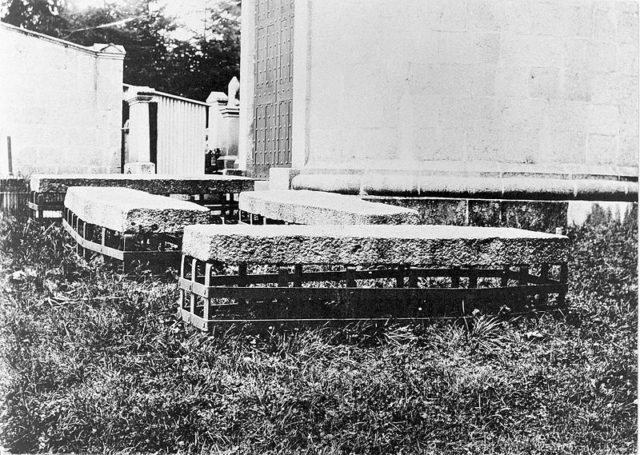

Naturally, the relatives of the deceased were both disgusted and afraid of the idea that their family member might end up stolen instead of left to rest in peace. For this purpose, the Mortsafe was used. By design, it is a steel cage shaped like a coffin. It was placed over the grave and insured that the deceased remained buried; there were even watchtowers erected where guards kept a close eye to the graves and made sure no snatcher came near.

But the mortsafe and the vaults and the mausolea were things that only the folks of the upper class could afford. The poor and poverty-stricken had to guard their own graves for weeks on end. Another invention, known as “Coffin Torpedoes” did a similar job to the mortsafe. The only difference was the coffin torpedoes were deadly. Patented in 1878, this contraption used springs and triggers to catapult lead balls into the air.

The mortsafe and the coffin torpedoes did their job well until 1832. Once the general public learned that this gruesome practice was getting out of hand, massive riots followed. That is when the Anatomy Act was passed.

With this act anyone who wished to dissect a body should first obtain a license. There were also inspectors that made sure there was no illegal dropping of cadavers.

To this very day, there are mortsafes scattered across graveyards throughout the world, reminding the living that there were times when even the dead weren’t safe from kidnapping.