Ötzi – a mummified corpse – was discovered in 1991 as the ice receded in the Ötztal Alps, hence his nickname.

The body was originally believed to be that of a mountaineer who had recently died, or even that of an Italian soldier from the First World War.

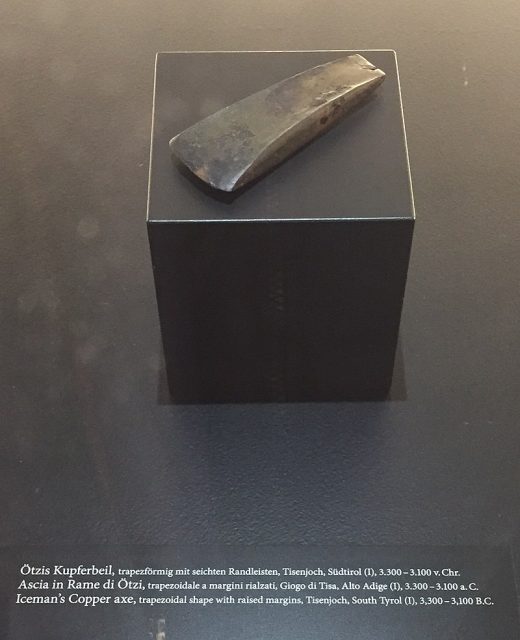

However, when archeologist Konrad Spindler, at the University of Innsbruck, examined it and a number of objects found with the body, he found it to be “about four thousand years old,” based on one of the axes that was found among Ötzi’s belongings.

Almost immediately the body drew much attention. For starters, it was incredibly well preserved.

The ice pocket into which Ötzi had fallen was so protective that it kept his brain, internal organs, some hair and one of his eyeballs completely intact.

Since its discovery, Ötzi has been thoroughly measured, analyzed, examined, x-rayed, and dated. When he was briefly “thawed out” in 2010, scientists were even able to retrieve some red blood cells – the oldest ever identified.

Remarkably, during all this intensive investigation of whom he was, scientists realized, thanks to a rare mutation known as G-L91, that Ötzi has living relatives in Austria’s Tyrol region. Cousins, only 10,000 to 12,000 years apart.

It was also discovered that this 46-year-old man had a number of health issues, including gallstones, worn joints, a growth on his foot, as well as worms and possibly Lyme disease. However, this was not what killed him. He was murdered.

Ötzi was found with a wound in his shoulder, as well as a head contusion. He had deep cuts on his hands, and the arrow flinthead had lodged in his shoulder (it was found in 2001), severing a major artery and causing him to quickly bleed to death.

Scientists noticed a clotting chemical that shows up in human blood after a wound is inflicted, but disappears quickly as well. However, the fact that it was found in Ötzi implies that he died shortly after receiving the wound.

Disturbing occasions when ancient Egyptian curses seemed to come true

In addition to the arrow wound, when he was examined by a CAT scan in 2013, researchers found a contusion at the back of his head, but they weren’t sure if it was caused by a fall after being hit by the arrow, or from another weapon.

The cut on his right hand had not yet healed, indicating that he may have been in a fight a few hours or even days prior to being shot with the arrow.

Scientists have determined recently that Ötzi was right-handed, and being injured would have made it harder for him to prepare or hold his weapons to defend himself from further attack. This may explain why the bows and arrows that were found with the body were not yet finished.

While the arrow would have caused massive bleeding, researchers found that the shaft had been removed before Ötzi died. What is more, the undigested meal of bread, sloes, and deer found in his stomach suggests that Ötzi was ambushed.

As much as we know about Ötzi, one thing about his death remains a mystery: motive. Ötzi was likely on the run from someone, or several people, but who or why we will never know.

It wasn’t a robbery – a valuable copper ax was found with the body. DNA analyses performed in the last few years have revealed blood from at least four other people on Ötzi’s equipment, including his knife, two samples on an arrowhead, and his coat.

Researchers have interpreted that perhaps he carried a wounded comrade over his shoulder, hence the blood on his coat, and he may have killed two people with the same arrow. Was his death revenge for theirs?

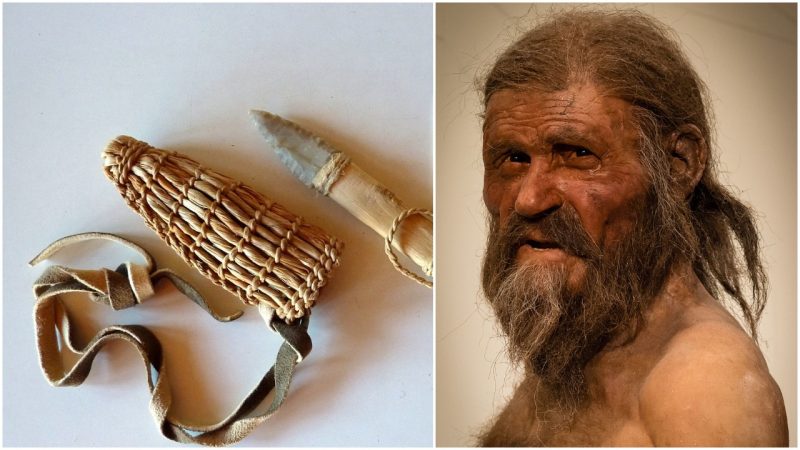

In 2011, researchers used 3D images of the preserved remains to recreate an incredibly lifelike reconstruction of Ötzi’s face. Since then, his entire body has been reconstructed.

He was 5 feet 3 inches tall, and weighed around 110 pounds (50 kilograms). With brown hair, deep-set eyes, and a long nose, he has even been said to resemble Harvy Keitel. Ötzi has been on display since 1998 at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career. She has lived and traveled all over Canada and Europe.