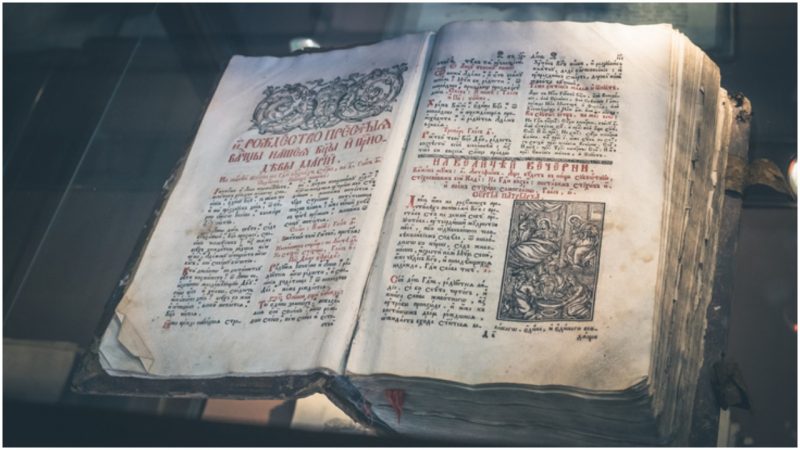

In a plot twist out of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, three rare books from the 16th and 17th centuries held in a library collection were found to be laced with deadly poison, according to a paper published on June 27, 2018, by researchers of the University of Southern Denmark.

The last thing that the researchers expected was poison.

“The reason why we took these three rare books to the X-ray lab was because the library had previously discovered that medieval manuscript fragments, such as copies of Roman law and canonical law, were used to make their covers,” wrote Jakob Povl Holck and Kaare Lund Rasmussen in the academic journal The Conversation. “It is well documented that European bookbinders in the 16th and 17th centuries used to recycle older parchment.”

To discover the possible age of the recycled materials contained in the cover and bindings of the books stored at the University of Southern Denmark, the researchers used the most modern technology available: a series of X-ray fluorescence analyses (micro-XRF).

“This technology displays the chemical spectrum of a material by analysing the characteristic “secondary” radiation that is emitted from the material during a high-energy X-ray bombardment,” wrote Holck and Rasmussen. “Micro-XRF technology is widely used within the fields of archaeology and art, when investigating the chemical elements of pottery and paintings, for example.”

While trying to identify the Latin texts used in the books, the researchers were frustrated by a layer of green paint that obscured the old handwritten letters.

They decided to analyze the mysterious paint, and XRF tests revealed “that the green pigment layer was arsenic. This chemical element is among the most toxic substances in the world and exposure may lead to various symptoms of poisoning, the development of cancer and even death.”

Depending on the type of arsenic used and the duration of exposure, symptoms of arsenic poisoning include an irritated stomach, irritated intestines, nausea, diarrhea, skin changes and irritation of the lungs. The exposure’s harmful effect has not gone away, either.

Why would anyone use poisonous paint on these obscure books?

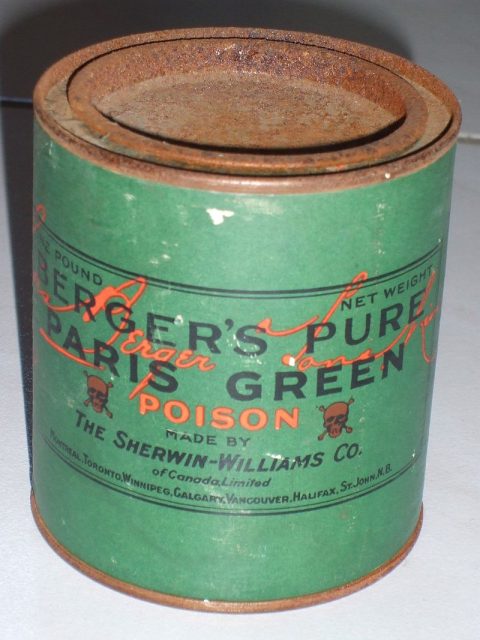

The answer seems to lie in the 19th century. Arsenic was commonly used to create the “Paris green” paints and lacquers and was most likely employed on these books by well-meaning restorers.

10 Most Poisonous Things on Earth!

Wrote the university researchers: “The arsenic pigment – a crystalline powder – is easy to manufacture and has been commonly used for multiple purposes, especially in the 19th century. The size of the powder grains influence on the colour toning, as seen in oil paints and lacquers. Larger grains produce a distinct darker green – smaller grains a lighter green. The pigment is especially known for its colour intensity and resistance to fading.”

Why would anyone want to improve the aesthetics of 17th century books?

Most likely, artistic effect was not the only thing on their minds in the 19th century. There was a byproduct of using the “Paris green” color: it protected manuscripts against insects, rats, and other vermin. People of the time might not have understood why, but the paint kept the books safe.

By the second half of the 19th century, however, the deadliness of arsenic was known, and it was no longer used as a paint pigment. “Grim stories of green Victorian wallpapers taking the lives of children in their bedrooms are known to be factual.”

However, the farmers still made use of it on crops. “Other pigments were found to replace Paris green in paintings and the textile industry etc. In the mid 20th century, the use on farmlands was phased out as well.”

As for the books in the Danish library collection, they are now stored in separate cardboard boxes with safety labels in a ventilated cabinet.

“We also plan on digitising them to minimise physical handling,” wrote the researchers. “One wouldn’t expect a book to contain a poisonous substance. But it might.”

Nancy Bilyeau, a former staff editor at ‘Entertainment Weekly,’ ‘Rolling Stone,’ and ‘InStyle,’ has written a trilogy of historical thrillers for Touchstone Books. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.