Isadora Duncan was a passionate dancer of the early 20th century. She was not a classically trained ballerina, however, that never bothered her. Instead of fearing critics and people in high society, Duncan bravely introduced what is now considered modern dance to the American and European scene. Her movements enchanted the audience and caused a revolutionary switch in the perception of the art of dance.

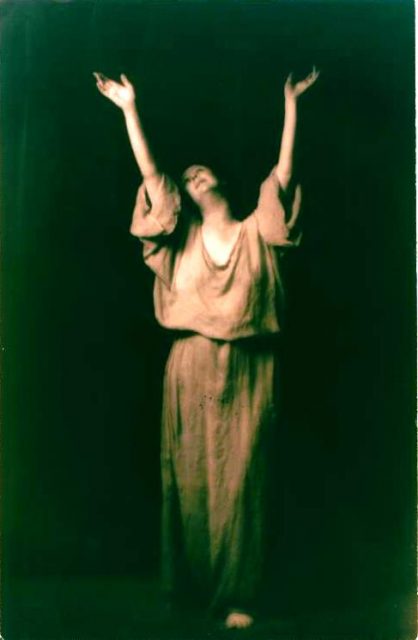

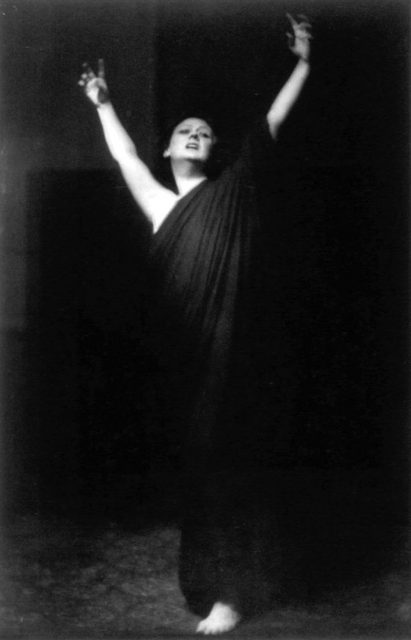

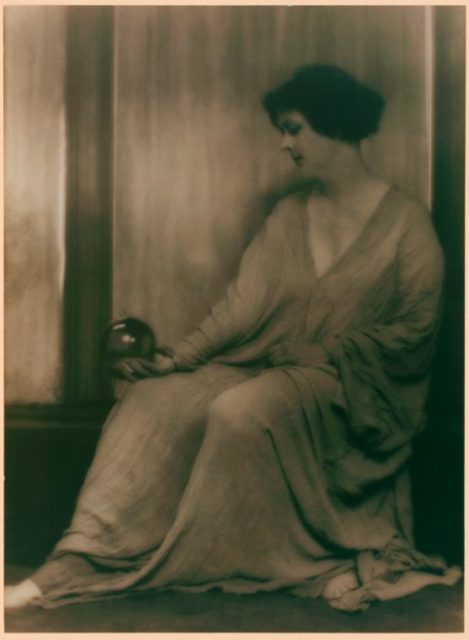

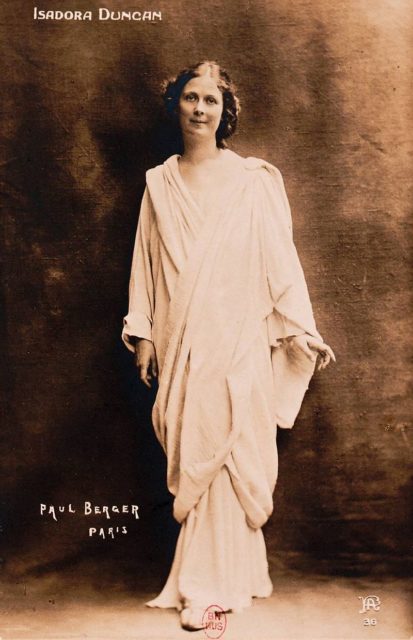

In a time where the world admired the strict, elegant movements of the ballet dancers in short tutus and stiff shoes, Duncan danced barefoot, wrapped in flowing scarves and togas. She drew her inspiration from Greek art, bringing mysticism to her “free-styled” movements. The result was worldwide recognition.

She was born in 1877 in San Francisco, California. Her parents divorced, and Isadora was raised by her mother, a piano teacher with a great appreciation for the arts.

Just like her three other siblings, Isadora grew up in the rhythm of the music. By the age of 6, she was giving dancing lessons to the children in her neighborhood, to contribute to the household income.

By the age of 10, Isadora’s classes became quite popular and she requested to leave school so that she could teach all day long with her older sister.

Dancing full time during her teenage years, Isadora started experimenting with her choreography. She studied dance iconography and ancient dance rituals, which helped develop her abstract style. Dancing was her expression of living.

A free-spirited bohemian, Duncan rejected social norms, both onstage and off – she was a feminist, a Darwinist, a Communist (for which her American citizenship was revoked in the early 1920s), a bisexual, and an advocate for free love. All of this earned her the reputation as an eccentric, but also a lasting legacy.

In New York, she joined Augustin Daly’s theater company and later took ballet lessons from Marie Bonfanti, but she stuck with neither for long, disliking the rigid formality.

Disillusioned, Duncan moved to London in 1898. There she danced in the homes of upper-class people, while drawing her inspiration from Greek art in the British Museum.

After London, Isadora moved to Paris, the artistic cradle of the time, where she frequently visited the Louvre, another source for her dancing ideas.

The audiences loved Duncan’s performances. In 1902, she toured all around Europe with Loie Fuller, breaking the accepted norms and perceptions about the art of dance.

Critics were divided. Some were disturbed by her “disrespect” towards classicism while other praised her courage and talent. And fellow artists embraced her. She inspired many of them, including Arnold Ronnebec, Antoine Bourdelle, Abraham Walkowitz, and Auguste Rodin.

In 1904, Duncan opened her first dancing school just outside of Berlin, Germany. There, she trained girls, dubbed the “Isadorables” by the French poet Fernand Divore. Isadora legally adopted six of them in 1919 who became her protégées and continued her work after she died.

Utilizing composers such as Beethoven, Wagner, and Chopin, in her comfortable, Greek tunic, Isadora performed her revolutionary movement in front of European royalty, as well as Vladimir Lenin.

In 1911 there was a lavish party hosted by the French fashion designer Paul Poiret in a rented mansion, the Pavillon du Butard in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, where Duncan danced barefoot on tables among 300 people and 900 bottles of champagne.

While she thrived professionally, Isadora’s private life wasn’t a very happy one. She had many relationships with both men and women, including Mercedes de Acosta.

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/_tByMJA-HQQ

In 1906 she gave birth to her first child with theater designer Gordon Craig, and in 1910 she had a second child with Paris Singer. Unfortunately, in 1913, both of them drowned with their nanny when their car lost control and fell into the River Seine.

Isadora never fully recovered from the tragedy, but continued to tour Europe and America. She moved to Moscow in 1921 to start a new school with Isadorable Irma Duncan. It was here she met the poet Sergei Yesenin, 18 years her junior.

The two got married so that Yesenin could join Duncan on her tour in the U.S. However he returned to Moscow after a few months, separating from his wife. A few years later, in 1925, he committed suicide.

In the following years, Isadora found comfort in alcohol and numerous love affairs. Her absence from work led to great debts, but she seemed drowned in the sadness caused by the previous tragedies. Her death itself was tragic and bizarre.

In 1927, Duncan was riding on the passenger seat of a brand-new convertible open-air sports car with friends in Nice.

She wore a hand-painted, long, red, and flowing silk scarf, designed by the artist Roman Chatov. The scarf was a present from her friend Mary Desti, who was also in the car.

As Duncan leaned back in her seat to enjoy the sea breeze, her long scarf became entangled in the well of the rear wheel on the passenger side. It wound around the axle, breaking her neck instantly and dragging her body onto the cobblestone street.

Duncan was cremated and her ashes were placed in the Columbarium at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, next to her children.