The idea of being paid in chocolate is a daydream enjoyed by workers around the world. But according to a new study, the deal might not be so far-fetched. Joanne Baron of the Bard Early College Network has been having a sweet time analyzing ancient Mesoamerican art, and she thinks she’s identified the specific use of cacao beans as currency in the Mayan culture.

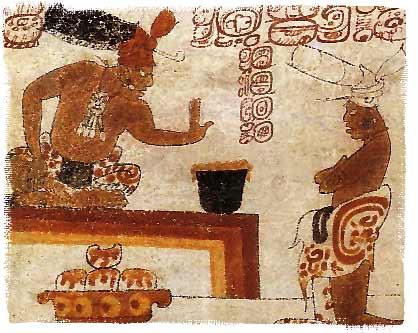

Cacao beans are the source of cocoa butter and cocoa solids, without which humans would never have discovered death by chocolate. Baron has presented an array of paintings, murals, and carvings, arguing that during the years 250-900 AD the status of these beans evolved from drinking to spending.

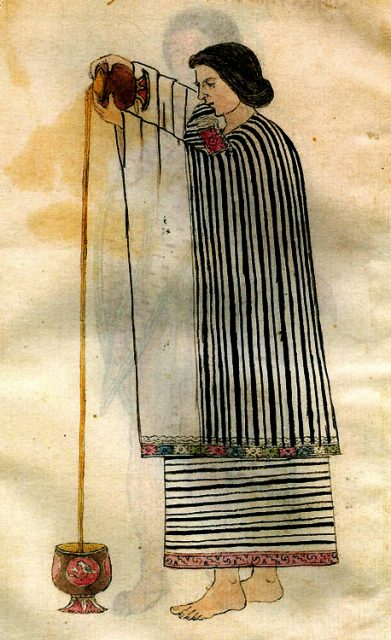

Up to that point the bean was used as the key ingredient in a delicious beverage, which was initially alcoholic in nature before becoming the hot and tasty treat people know today. In an article from last month, Science magazine talks about the role of trade in Mayan society:

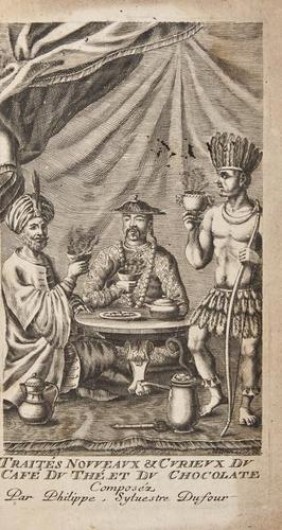

“The ancient Maya never used coins as money. Instead, like many early civilizations, they were thought to mostly barter, trading items such as tobacco, maize, and clothing.”

As well as the business of exchanging goods in the markets there were also royal tributes to consider. Mayan Kings required their willingly-given taxes, and it turned out cacao beans were a great way of settling the debt.

Around 11 million beans per year were accepted, giving the cream of the crop — an endless supply of the dark and delicious material.

This is shown in the art Baron has been poring over, leading her to think that chocolate went beyond its long-established religious and cultural significance to something more financial.

In her study, the details of which were published in Economic Anthropology, she argues: “(that) these products, originally valued for their use in status display, took on monetary functions within a context of expanding marketplaces among rival Maya kingdoms.”

The substance had been important to Mayans since its introduction, thought to be around 2000 BC. When the tomb of an ancient Maya King was found late last year, The National Geographic reported on the artifacts recovered with the bones, which it’s speculated are those of King Te’ Chan Ahk.

Among the artifacts were earthen pots, believed to contain “offerings such as tamales, chocolate, or other food items that were intended to accompany the dead into the afterlife.” Chocolate was so essential it accompanied those going to meet their Maker. And if that doesn’t sound profound enough, then how about a deity devoted to the stuff? Ixcacao is the fertility goddess associated with chocolate.

Baron goes on to say that ancient Maya could have fallen on the basis of cacao availability. With the relatively precious nature of the chocolate seed, it makes sense it would have value above that of other materials used by the Maya, like maize. The beans could only grow in certain areas and needed moist soil under a humidity level of 90%.

Of course, history is as much about filling in the gaps as it is hitting the nail on the head. The anthropologist and Maya expert David Friedel, who co-directed the research on the aforementioned tomb, has his doubts about Baron’s fascinating conclusion. Science reports and quotes him as follows:

“Freidel says the rise in artistic depictions of cacao may not necessarily indicate increased importance as a currency. As the Classic Maya period unfolded, he says, more and more people wrote things down and painted murals or pottery scenes. ‘Is it actually getting more important or are we just learning more about it?’”

However, with the Aztecs recording the use of cacao as a means of exchange, Baron seems confident in her theory. In her research, she concludes, “that money’s value in social relationships is not shaped by its materiality alone but by practices and discourses that frame specific material properties as valuable.”

Put simply, if a crop can be money, then why not other consumables? Either way, the investigations will continue, perhaps with a mug of hot chocolate to keep those scientific brains ticking over.

Steve Palace is a writer, journalist and comedian from the UK. Sites he contributes to include The Vintage News, Art Knews Magazine and The Hollywood News. His short fiction has been published as part of the Iris Wildthyme range from Obverse Books