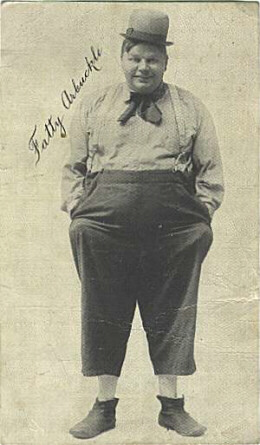

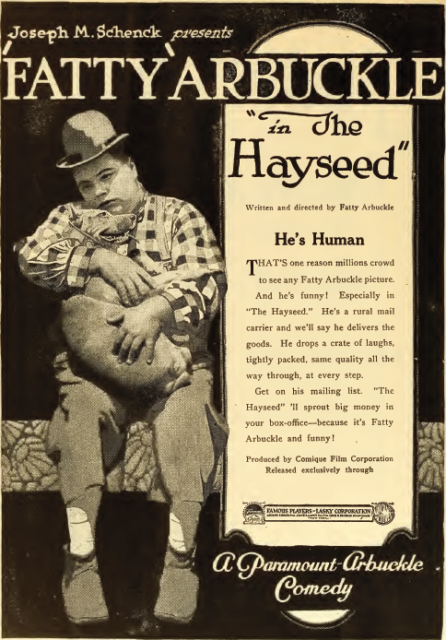

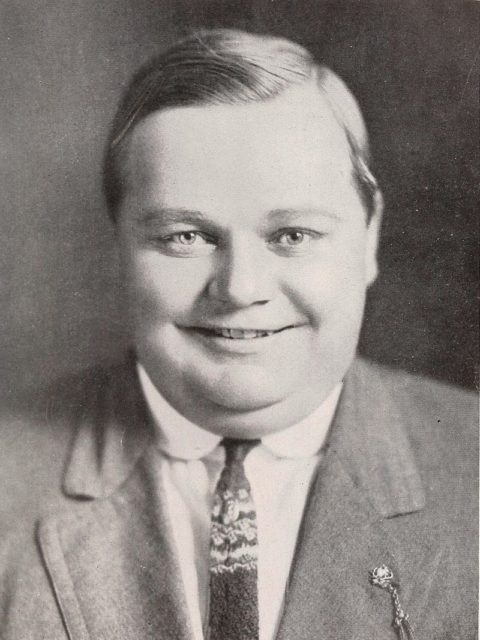

Back in 1921, Hollywood tasted the flavor of its first big fatty scandal. It roared from the front pages of newspaper magazines and concerned one Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, the silent era movies mega-star who had a million-dollar contract with Paramount. If there was but one actor more famous than Arbuckle, it was Charlie Chaplin.

With the flick of a finger, the fortunes changed for Arbuckle. The comedian — noted both for his extra hundred pounds as well as the exceptional agility he retained on screen — became one of the most detested persons nationwide. He was no longer worshiped for his acting but was suddenly hated for a wrongdoing, of which some details are puzzling even to date.

Along with his friend Fred Fischbach, Arbuckle traveled to San Francisco for some liquor-fueled partying during Labor Day break. They checked in at the St. Francis Hotel, where an opulent-looking suite awaited them, ready to accommodate what would be a gin party with a crowd of people.

According to Smithsonian, the days ahead of the partying were not the best ones for Arbuckle. He needed the break to recover from a busy filming schedule. Also, he had just suffered an accident in a garage where he was having his car fixed. He sat on a rag soaked with acid, which gave him second-degree burns. Arbuckle even wanted to call off the entire San Francisco thing, but his friend Fishbach was persistent they proceed with the plan.

Had he canceled, Arbuckle would have surely saved himself from all the troubles that were to follow.

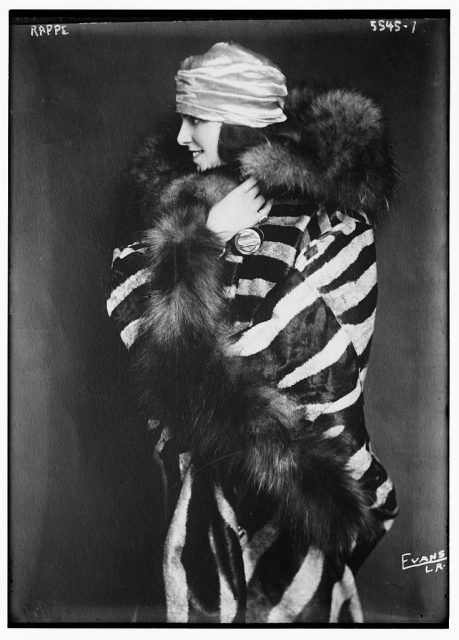

Among the party attendees on September 5th that year, was an aspiring young actress, Virginia Rappe. She had experience as a fashion model and clothes designer, was a known party-goer, and her film career measured a limited success.

At one point during the evening, her screams were heard outside room 1219 and she was found lying on the bed, twisting in agony. A few days later, doctors pronounced her dead. The finger of blame was pointed towards Fatty Arbuckle.

Someone else was involved in the situation: a woman by the name of Bambina Maude Delmont, an alleged friend of Virginia Rappe who came forward as a witness of the case, though she was never called by the prosecution to testify. Delmont testified she heard screams from the hotel bedroom after which Arbuckle emerged from the room, saying, “Go in and get her dressed and take her back to the Palace. She makes too much noise.”

Delmont allegedly heard Rappe say “Arbuckle did it.”

This was enough to ruin both Arbuckle’s career and shake the foundations of Hollywood.

For the first time, people across the nation had a taste of the sordid life, the real affairs of the stars they were so keen on seeing only in theaters.

According to Arbuckle, he had done nothing wrong to the young actress. He insisted on his innocence, that he found Rappe in the bathroom in a very bad condition and vomiting. According to his statements, he and other guests tried to help her as everyone assumed she had consumed too much liquor. She was accordingly accommodated in a room alone to recover and attended by a doctor.

In the following days, Rappe’s condition worsened and she was hospitalized. Delmont insisted that Rappe had been sexually assaulted by Arbuckle, but a medical check reportedly did not find traces of abuse. Rappe died from secondary peritonitis caused by a ruptured bladder.

For Arbuckle, this all meant an accusation of manslaughter. The Yellow Press fed on it and generated sensational headlines that proved fatal for the actor. Their depictions of him were monstrous.

The case equally attracted activists. Some of their demands were that Arbuckle should face the death penalty. Hollywood executives were quick to disassociate from Arbuckle. Everything was happening before any conclusion in the trial was reached.

However, Delmont, the principal person laying blame on the comedian, was someone with a criminal record in her portfolio. Allegedly, she already had a track record for sending young women to parties attended by rich people. Men were later accused of sexual assault and blackmailed by Delmont and her network.

The woman later admitted to plotting in the Arbuckle’s case too. It was further revealed that some witnesses called in the trials were also intimidated to share statements that proved damaging for the comedian.

Delmont’s statements were also inconsistent. At one point, she reportedly claimed to be an old friend of Rappe, and in another one, she persuaded everyone the two had met each other only a couple of days before the party.

Arbuckle was tried three times before he was ultimately cleared of the charges. The first and second rounds ended in a hung jury. During the third one, which took place in 1922, it took judges no less than six minutes to unanimously free the comedian of charges. He was found guilty only on the grounds of illicit alcohol consumption (this was still the Prohibition era).

The judges also offered an apology to Arbuckle, concluding that the entire case was “a grave injustice” towards him. They further claimed that “there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime.”

Related Video: Rare footage of Laurel and Hardy’s only TV appearance:

Although Arbuckle was cleared, his case had significant implications all around Tinseltown. For one, this was the first case which affected the box office. As the scandal erupted, his films were pulled from theaters.

The case further helped the foundation of a Hollywood censorship board, according to the BBC. This board was quick to dismiss Arbuckle, not allowing him to take any new work. He was removed from the blacklist a few months after the case was resolved.

Perhaps most painfully for Arbuckle, the public was not convinced of his innocence. His name remained blackened by whatever it was that happened that Labor Day in the St. Francis Hotel. He had lost both his fame and fortune.

Ahead of him, there was a long road to recovery from the nightmare. For a decade, Arbuckle worked as a director under the new name of William B. Goodrich (Will B. Good). He died from a heart attack in his sleep, in 1933, aged 46.

Stefan is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to The Vintage News. He is a graduate in Literature. He also runs the blog This City Knows.