Bread-lines. Soup-lines. “Brother, can you spare a dime?” Street corner apple sellers. Stockbrokers jumping from Wall Street windows. Riding the rails. All of these things are emblematic of the Great Depression (1929-c.1941), the greatest economic disaster to befall the United States and the world in modern times.

In the recession that began in 2007-8, the US unemployment rate reached ten percent in some states. During the Depression, the jobless rate at times hit thirty percent in some areas of the country. This, of course, led to homelessness on a massive scale.

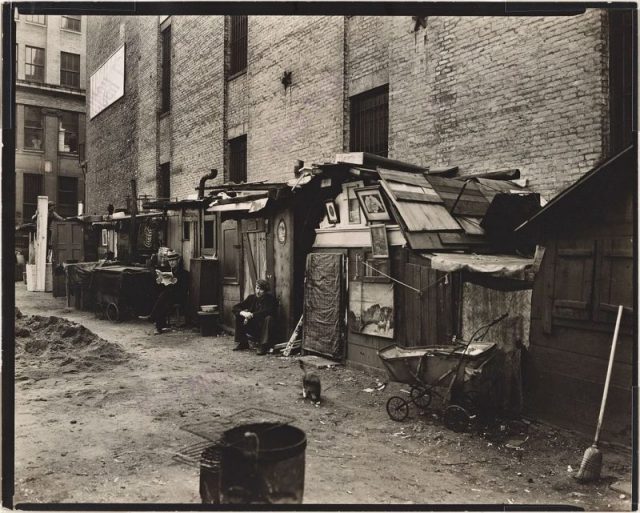

To find shelter, protection, and community, people all over the nation constructed “Hoovervilles” – essentially temporary slums named after the man that most people blamed for the Depression – President Herbert Hoover.

The Depression lasted a little over two years before the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his “New Deal” which would see greater social programs and benefits for those affected by the Depression.

Social Security, welfare and unemployment benefits were begun under Roosevelt, and like today, provided a bare minimum to “tide people by” until times got better. In the 1930s this bare minimum still did not allow many to regain any kind of permanent shelter, so they stayed in the Hoovervilles.

Perhaps the largest Hooverville in the country was in St. Louis, then one of the ten biggest cities in the nation, and for many, a crossroads going both east/west and north/south on their way to other destinations hoping to find work. Like all Hoovervilles, the one in St. Louis was made up of make-shift buildings made from whatever people could get their hands on.

1930s Slang

The most common sights were scrap-wood and tar-paper shacks. This at least kept out some of the cold in winter. Heat was provided by whatever would burn – usually in metal oil drums, but sometimes in wire garbage cans, both of which allowed sparks to escape. Tar-paper catches fire quickly, and this was an ever-present threat in the community.

The threats of fire and of crime led to the residents of the Hoovervilles to band together to create fire-watchers and unofficial police forces. The majority of the residents of the slums were single men, or married men separated from their families. Any social worker will tell you that crime goes up in a community without women and family present.

Though men made up the majority of the residents, their were still plenty of women and children – the typical victims of crime. Within many of the Hoovervilles, some of the older and/or more responsible men formed vigilante groups responsible for keeping (or trying to keep) law and order. It is not hard to imagine that many cases of domestic and child abuse went unpunished, however.

Another way people tried to cope with their situation was to have regular religious meetings. In St. Louis, their were no less than seven churches made from orange crates trying to furnish the spiritual needs of those living there.

Schools were also opened for the children in the camp. Seven churches? That begs the question: how many people lived in the St. Louis Hooverville? Historians estimate anywhere from five to seven thousand – this number was constantly changing as times got worse or better.

The other obvious problem for a community of this size, which was in almost every sense of the word a “refugee camp,” was health. In the summer, heat added to the misery. Water was limited, making clean drinking water a scarcity.

The camp in St. Louis was right on the Mississippi River, and clean water was still scarce. Why? Think about it – in a time before any true regulation on pollution, many of a major cities’ factories dumped right into the river.

Same with much of the cities’ waste. Add to that the waste, food remains, and garbage of the camp itself. Though there were outbreaks of water-borne illnesses in the U.S. during the Depression, it’s amazing that there were not more.

Health questions as well as questions of law and order, “civic pride” (which meant “appearances”) led many of the cities in the United States to closely monitor the Hoovervilles with the police. Though the Hooverville in St. Louis lasted for most of the Depression, many of those in other cities were broken up, sometimes very forcefully.

Another factor leading the authorities to watch and break-up the Hoovervilles, especially in the first years of the crisis, was the fear of communism. Ever since the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the nations of Europe and North America feared that communist ideology would spread among the working class.

To degree, it did, which resulted in the “Red Scare” of the 1920s, and the wide-spread fear of communist revolution during the Depression. Within most Hoovervilles, one did not have to look hard to find socialist and communists among the workers laid off from their jobs.

While most of those laid off were not communists by any stretch of the imagination, the powers that be in business and government were gripped by fear that labor unions (whom they already suspected) would soon be advocating violent revolution. At times, workers’ meetings in the Hoovervilles were both infiltrated and broken up by the police.

Read another story from us: The reason why some Great Depression photos were punched full of holes

With the coming of WWII, and America’s role in helping to supply the British Empire and itself with the weapons and supplies of war, the Depression slowly came to an end, and with it, those Hoovervilles still standing were thankfully abandoned, but they live on in the poignant photographs.

Matthew Gaskill holds an MA in European History and writes on a variety of topics from the Medieval World to WWII to genealogy and more. A former educator, he values curiosity and diligent research. He is the author of many best-selling Kindle works on Amazon.