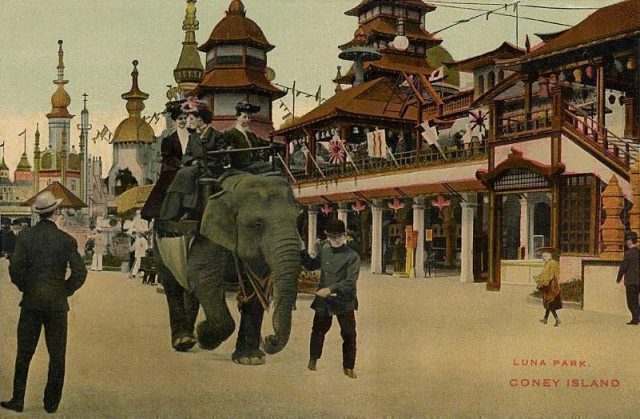

A baby elephant, brought to New York’s Coney Island amusement park in 1902, under the guise of wholesome family-friendly entertainment, would become a tragic and shameful symbol of man’s unfathomable cruelty towards animals. It would also, oddly enough, spawn a legend involving Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla.

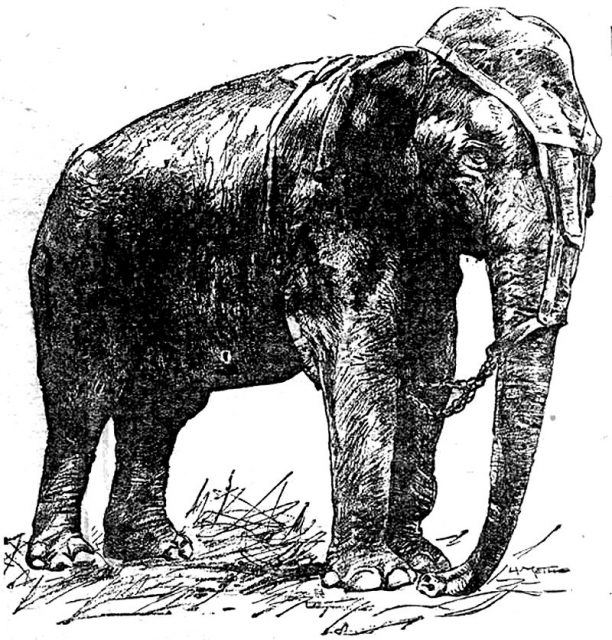

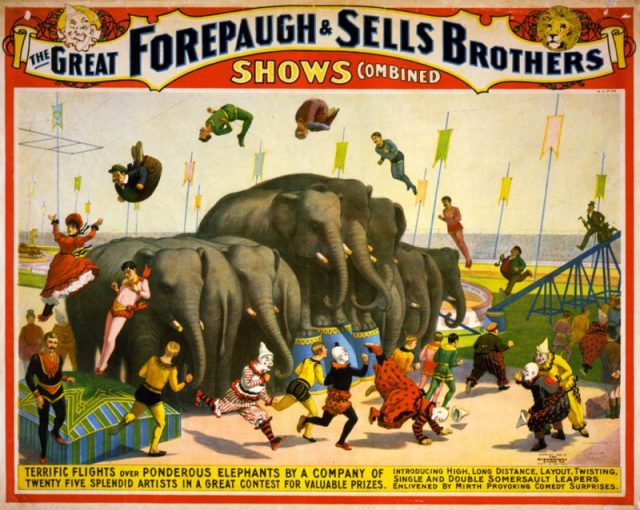

Topsy was a female elephant born in Southeast Asia and brought to the U.S. soon thereafter (illegally, it turns out) to join a group of performing pachyderms at the Forepaugh Circus. During the 25 years she was there, Topsy gained a reputation as being dangerous.

After killing a spectator in 1902, she was sold to Coney Island. While there, Topsy was involved in several incidents and again deemed unmanageable. More than likely, though, her behavior was the result of cruel treatment at the hands of her handler, who used a pitchfork to keep the animal in line.

A plan to hang the out-of-control Topsy was hatched by the park’s publicity-mad owners, Thompson & Dundy, who decided to charge admission to the event. In stepped the SPCA, who claimed this method of execution was unnecessarily cruel.

The owners agreed to switch to a more “sure” method of execution: a mix of poison, strangulation, and electrocution. On a frigid January day, Topsy was fed carrots laced with potassium cyanide, a rope was placed around her neck, and her feet were fitted with electrodes. The switch was hit and 6,000 volts were sent coursing through her massive body. It took just ten seconds before she fell over and died.

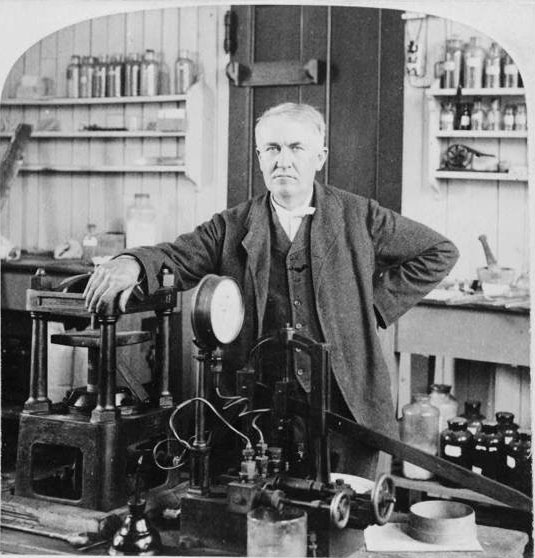

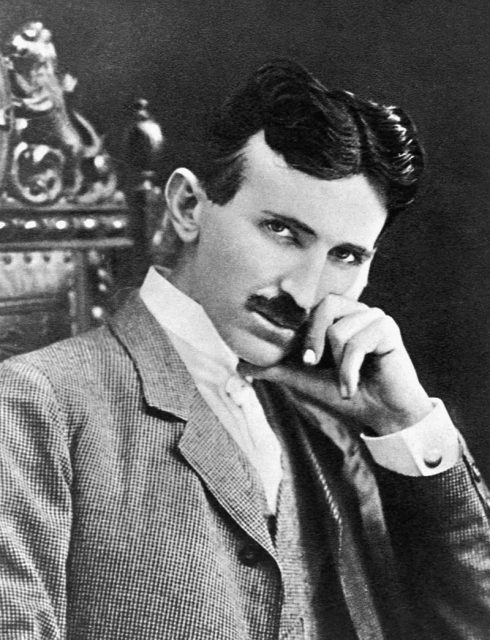

Some believe that Topsy’s electrocution may have been set in motion because of an intense rivalry between inventors Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. In the late 1880s, electricity was still in its infancy, with gas lamps being the predominant source of light.

The War of Currents, as it would become known, would determine the way people powered their homes and businesses in the future. On one side was Thomas Edison’s direct current (DC) system; on the other, an alternating current (AC) from Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse.

Each side touted their method as being more efficient (and more importantly, safer) than the other’s. Tesla’s AC would eventually win out in the years to come, but no matter. Edison, realizing that AC generators were spreading across the country faster than his DC alternative, knew he had to resort to desperate measures: In short, launching a full-out propaganda campaign to discredit his rivals.

Edison began questioning the safety of the Tesla-created system — at one point, issuing a dire warning: “Just as certain as death, Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size.”

To prove his point, Edison began conducting a series of grisly experiments designed to demonstrate just how dangerous this new form of electricity, AC currents, could be, by using it to electrocute animals — dogs (many provided by the SPCA), calves, even a horse — at his West Orange, NJ, laboratory.

In one gut-wrenching demonstration, done in full view of reporters, Edison poured water on a sheet of tin, attached it to an AC power source, then invited a dog to lap up the liquid. The animal fell over dead as soon as its mouth came in contact with the electrified tin.

The story goes that Edison set his sights on an even more impressive target: Topsy, the “murderous” circus elephant who was about to be put to death. Edison, it was believed, hoped the spectacle — secretly, an anti-AC demonstration — might stop Tesla’s AC from gaining ground. If the current could take down an elephant that quickly, how dangerous, Edison reasoned, might it be to humans?

The Edison Manufacturing movie company was there to film the event. Their short, silent, black-and-white documentary, entitled “Electrocuting an Elephant,” can be seen on YouTube today, for those that have the stomach.

However any direct involvement by Edison himself has since been put into question. More than likely the film company, which at the time was connected to the inventor in name only, simply saw the electrocution as an interesting human interest story.

Read another story from us: The Most Beloved (and Highest Paid) Dog in Golden Age Hollywood

What’s more, historians point out, the War of the Current ended around 1892, some ten years before Topsy’s death. Regardless, not a banner for technological breakthroughs, nor animal rights.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.