When we think of Vikings, what often comes to mind are images of men in horned helmets and long cloaks, sailing off to conquer and pillage various parts of Europe. Well… that, and berserkers. The idea of the berserker is fairly well known in many parts of the world, if only imperfectly understood.

What was a berserker? Berserkers were a particular subset of warriors in pre-Christian Scandinavia. They were a traveling brotherhood who would take service with different chiefs, according to History Extra.

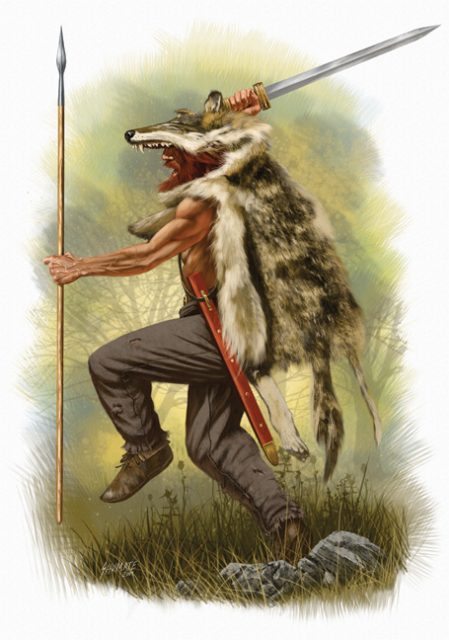

They usually were used in small groups, often about 12, in addition to the regular guard or army. What set them apart from other warriors was that they had bears or wolves as totem animals, and wore their skins into battle. They believed that when they were fighting, they took on the attributes of their totem animals.

Berserkers were elite shock troops, highly coveted, but difficult to control, since they fought in a state of battle rage which made them both nearly supernaturally strong and fierce, but also dangerous.

In battles, they were placed at the front of a phalanx, either to launch an attack or resist the main weight of an attacking force. In sea battles, they were usually put in the prow of the ship to be the first force meeting the enemy.

Berserkers, were, however, poorly suited to formation warfare, since when they were in their battle frenzy, they were nearly impossible to control and could attack the enemy, but would also attack trees, rocks, or each other.

It was said that they went into battle wearing little but loincloths and the skins of their totems, to show disdain of wounds, and carried only light shields for protection. The Norse saga, The Ynglinga Saga, says these were Odin’s warriors and that his men “rushed forwards without armour, were as mad as dogs or wolves, bit their shields, and were strong as bears or wild bulls, and killed people at a blow, but neither fire nor iron told upon themselves. These were called Berserker.”

In other sagas berserkers are often painted as being violent and out of control, and as being evildoers in their frenzy.

Is this a fair and accurate portrayal? Norse Mythology suggests that berserkers should be considered as shamanic warriors or warrior-priests. During the Viking Age, all warriors looked to Odin for strength and courage in battle, but the berserkers were much more tightly bound to the cult of Odin.

They used a set of ritual practices, such as wearing the skins of their totem animals, in order to help remove their humanity and become a divine predator. They might have had an initiation process where they would go into the woods to live like their totem animals, hunting, gathering, and raiding the nearest towns. Such practices were to help induce an altered state where they could take on the characteristics of their totems.

Check out 10 interesting things you may not know about the Vikings here:

In such an altered, dissociative state the berserkers would experience battle-rage to the extent that, while it continued, they simply wouldn’t feel any injuries that they suffered (fire and iron won’t bite them).

The biting or casting away of their shields can be viewed as an act of further stepping away from their normal social personae, since, for a regular warrior, his weapons and shield were literal signs of his status and social standing, given to him as a young man when he came of age.

In 1784 a priest named Odmann theorized that the “going berserk” was brought on by consumption of fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) mushrooms. His theory gained popularity over time, and remains common today. Other toxic mushrooms have also been suggested as the source of the battle rage, but usually, the side effects of such plants are depressive symptoms, not rage and euphoria.

It seems far more likely that the warriors worked themselves up by ritual acts – war dances, or other rituals – along with the wearing of their totem’s skins, to put themselves into the self-induced hypnotic state that allowed them to disassociate from their human identities and bond more tightly to their totem animals.

In that state, they could easily have increased strength and reduced sensations of pain, as well as a certain lack of awareness of their immediate environments. Critical thinking and social inhibitions would weaken, and more primitive responses come to the fore.

Under these conditions, it seems unfair, somehow, to judge berserkers in full battle-rage by the same standards as ordinary mortals, and much easier to see them as acting in communion with Odin.

Read another story from us: It’s Hammer Time! The Viking Method of Rap Battling

The Old Norse society and religion had room for this sort of behavior, but Christianity didn’t. As Scandinavia became increasingly Christian, and the old religion faded away, so too did the berserkers retreat into shadow and myth.