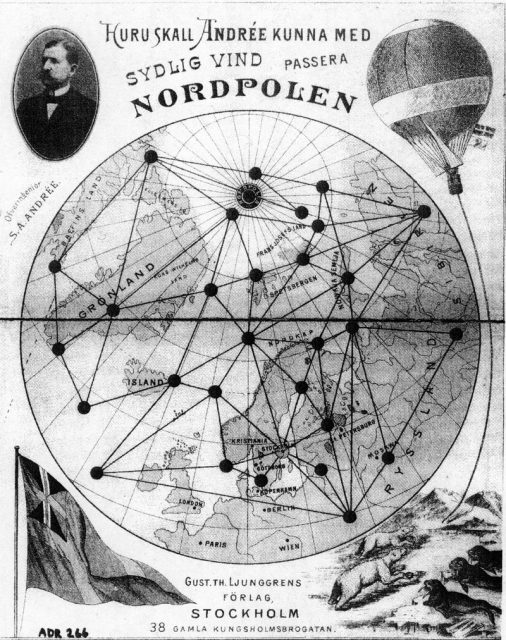

Salomon August Andrée (1854-97) of Sweden — better known as “S.A Andrée” — was an engineer and physicist, who like millions of others at the time, was obsessed with the Poles. Not Polish people, but the North and South Poles.

Attempts to reach the poles had gone on since men had developed large ocean-going craft, but it wasn’t until the 20th century that people reached the North and South Poles. (A 1909 claim by American Robert Peary is doubtful. It is likely that both poles were verifiably reached first by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, South in 1911, North in 1926.)

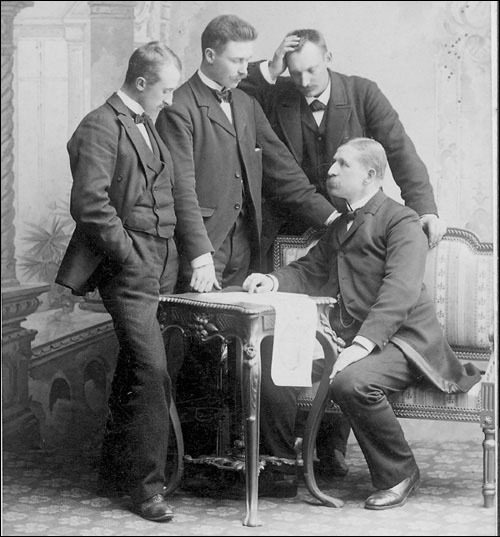

One earnest but quite ill-conceived attempt was undertaken by Andrée and two of his Swedish countrymen, another engineer, Knut Fraenkel, and photographer Nils Strindberg.

Andrée believed that the best way to reach the North Pole would be during the “gentle” polar summer when winds blew predominantly northward and were not too strong. The best way to reach the Pole, according to Andrée, was by balloon.

Though ballooning had been around since the French Montgolfier brothers in the late 1700s, balloons still captured the imagination and many saw great potential in them – for travel, observation, warfare, etc. Andrée believed he could accurately fly a balloon from the coast of Norway to the North Pole.

There were many problems with Andrée’s idea. One, he had very limited experience with balloons – very limited. He had traveled to the United States in 1876 during his studies to work in the Swedish Pavilion at the American Centennial Exposition as a janitor.

There, he met an American balloonist and became enthralled with the idea of balloon travel. Andrée graduated from college with a degree in mechanical engineering and later worked on an expedition to Spitsbergen Island where he did some experiments on electricity in the atmosphere.

This short period seems to have given Andrée the idea that he knew what he needed to know about the Arctic.

In his thirties and early forties, he worked for the Swedish Patent Office and was published in a host of scientific journals. He also developed connections and became a local politician. In the heyday of man triumphing over nature in the 1890s, Andrée convinced patrons such as the King of Sweden and Alfred Nobel of the merits of his idea of ballooning to the Pole. Both of these men and others funded Andrée’s idea.

Firstly, readers should know that Andrée decided that his balloon would be lifted by hydrogen. No, it didn’t catch fire like the Hindenburg later tragically did, but in the course of what was about to transpire, Andrée’s balloon rose faster than anticipated. Keep that in mind.

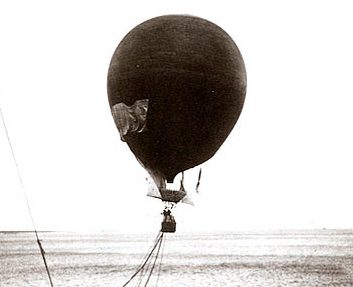

The main selling point of Andrée’s venture was that he believed that he could accurately steer his balloon using “drag ropes.” These would be hanging below the gondola, which would drag along the ground as the balloon, weighted by ballast, would fly at relatively stable altitudes.

Andrée also had a “sail” affixed to the balloon, which he believed he could use to steer the slow-moving balloon (due to the drag ropes) to whatever direction he wanted. Many experts told Andrée that there were a lot of problems with this and much else. Andrée didn’t listen.

First and foremost, Andrée hardly had any experience in ballooning. He took a few quick flights on a standard balloon on the Swedish coast – by all accounts, he was a terrible navigator. There was one attempted launch, but that was scrubbed due to high winds. The next summer (July 1897), Andrée and his team were back at it — with no additional flying time.

Second, the balloon was never inspected when it arrived from France. Only upon take-off was it discovered that it had a leak. That leads to problem number three.

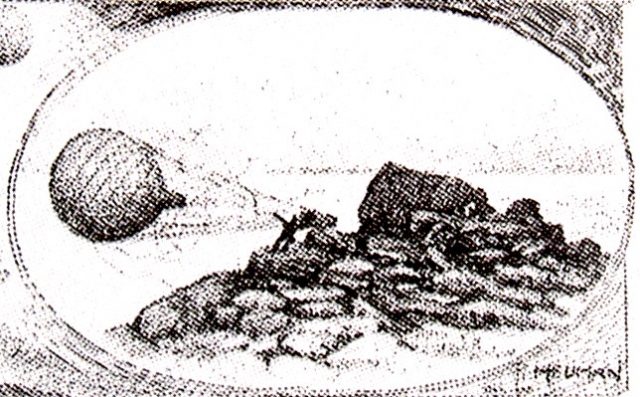

Third, the drag ropes were ineffective, and not only that, the ballast (weight) that they made up was lost when they became twisted in high winds and tore off. The “sail” was likewise removed.

Fourth, Andrée did have one good idea – an ice shield. Basically, this was a sheet draped over the balloon to absorb any ice build-up. Once the ice built up (which it did), Andrée would pull ropes to remove it and the sheet would take the ice with it. The problem was, there was only one sheet. In the end, that one good idea was a moot point.

Because, fifth, after losing the ropes, sail, sheet and bags of sand to gain altitude, the balloon started to rise too fast, which increased the leak of hydrogen that Andrée was undoubtedly now aware of. So, now, the two engineers and their photographer went bouncing over the Arctic ice. They ended sixty-five miles from where they started. They were never seen again – alive.

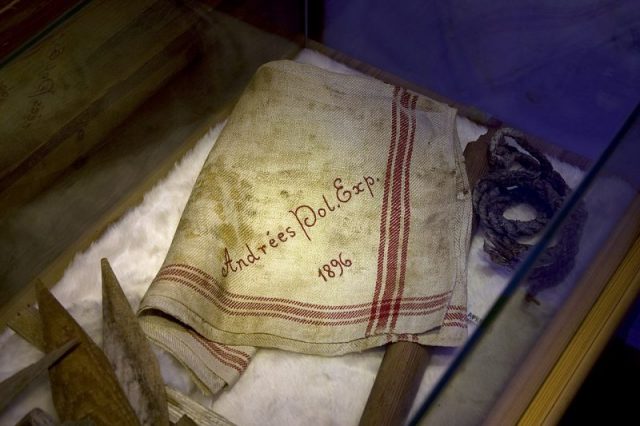

How do we know all this? Because Andrée kept a journal. It and the remains of the crew of the balloon (incidentally named “Örnen”, Swedish for “Eagle”) were found in 1930. With photographs detailing much of the early part of their trip, the crash and their attempt to stay alive in the much harsher than realized Arctic.

It soon became clear to the men that they had counted on succeeding – they would steer to the Pole, turn around and return home heroes. What need for adequate clothing?

They brought NO furs, only regular winter clothing and oilskins which seemed to just stay wet. Tents? Enough food? The men used the gondola to fashion a sled on which they piled canned foods, a tent, and whatever else they could carry – the sled was not made for use in the undulating pack ice and took too much energy to pull. However, they did have guns – though they had to abandon the beer, champagne and wine they brought.

The men believed they could trek over the ice back to their starting point, but after two days, they realized this would be impossible. They camped and walked until September, believing they might be able to survive wintering on the ice, but that plan was scrubbed after the ice began to crack under the makeshift hut/tent they erected.

They then made for the barren and unpopulated island of Kvitøya, where they made camp – and died, sometime after October 2nd, when the journal kept by Andrée becomes erratic and incoherent.

Read another story from us: The World’s First ‘Flying Aircraft Carrier’ and the Disaster that Ensued

Why didn’t they signal? They did. They left messages on floating buoys they had brought with them, but the only two found included messages from just after take-off. They brought homing pigeons as well, but no pigeon ever returned to base.