British people of the 19th century had an acute interest in crime — murder to be more precise. Gruesome cases of all kinds were abundant.

These were the days of mysterious serial killer Jack the Ripper, and baby harvester Amelia Dyer, and the multiple assassination attempts of Queen Victoria.

The rise of vicious city crime rates required a more serious approach to forensics. Fiction writers accordingly promoted the detective story as a genre.

So, what popular crime stories nurtured the public imagination in Victorian Britain?

Grisly confessions

Back in 1857, the life of 90-year-old Priscilla Guppy was coming to an end. As she laid on her bed in the Union Workhouse in Weymouth, Dorset, her last hours ticking by, she confessed to a crime she had kept silent for most of her life.

Guppy’s grisly misdemeanor took place while she was working in a brothel, some 65 years previously, in 1792.

When a fight broke out between two of the establishment’s clientele, Guppy decided to end it by hitting one of them several times with an iron.

Unfortunately, she crushed the man’s skull and he died. Helped by two men who witnessed the act, the woman wrapped the body in a sheet and dumped it beside the harbor bridge.

The terrible-looking, battered corpse was found the next day.

The police questioned Priscilla Guppy and her companions, but all three presented strong alibis and the case remained unresolved until her shocking confession. Guppy passed away shortly after, escaping trial yet once again.

The murdered man, Thomas Lloyd Morgan, who was aged 22 when he faced his demise, was buried in the local churchyard. Inscribed on his tomb were the words: “Here mingling with my fellow clay, I wait the awful judgment day, And there my murderer shall appear, Although escaped from justice here.”

The doctor that was up to no good

Various tales can be found of 19th century medical practitioners who turned out to be killers rather than healers. One of these was Dr. Thomas Neill Cream, who some people theorize could have been the notorious Jack the Ripper. He was, however, serving time for murder when most of Jack the Ripper’s crimes took place.

Born in Scotland in 1850 and raised in Canada from four-years-old, Cream studied medicine at McGill College in Montreal. Soon after graduating with honors in 1876, he and one Miss Flora Elizabeth Brooks had a “mishap,” which led to Cream’s first taste of abusing his position of power.

Not willing to accept responsibility for impregnating the young lady, Dr. Cream performed an abortion — an operation that poor Flora almost did not survive. The pair were forced to marry by her wealthy father, but Cream abandoned his new bride the day after the wedding and hopped aboard a ship bound for England.

There, he enrolled as a student at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London, where he specifically studied the effects of chloroform. This would be his favored means of subduing his victims, many of whom were prostitutes.

Eluding justice, he would move back and forth between Canada, the U.K., and the U.S. for years. Ironically, he first returned to Canada and set up an abortion clinic as a cover for his murderous thrill-seeking. When Cream was linked to a dead chambermaid, he swiftly relocated to Chicago. He was imprisoned in the Illinois State Penitentiary for murdering the husband of his lover (one of many), Julia Stott, in 1881, but was released early for good behavior. On gaining his freedom in 1891, Cream returned to London.

He was caught after his last round of killings, when he claimed the lives of his final four victims. In some cases, he poured in toxic compounds in the drinks of his victims then left the scene before even witnessing the effects of the poison. Dr. Thomas Neill Cream was hanged in 1892 for the murder of prostitute Matilda Clover.

What led Cream to the gallows was his own failure to keep silent about the terrible misconducts. First, he accused his neighbor of two of the killings. After that, he bragged about having extensive knowledge of the murders to a several acquaintances, and even gave two of them a tour of his crime locations around London.

The Victorian ‘Prince of Poisoners’

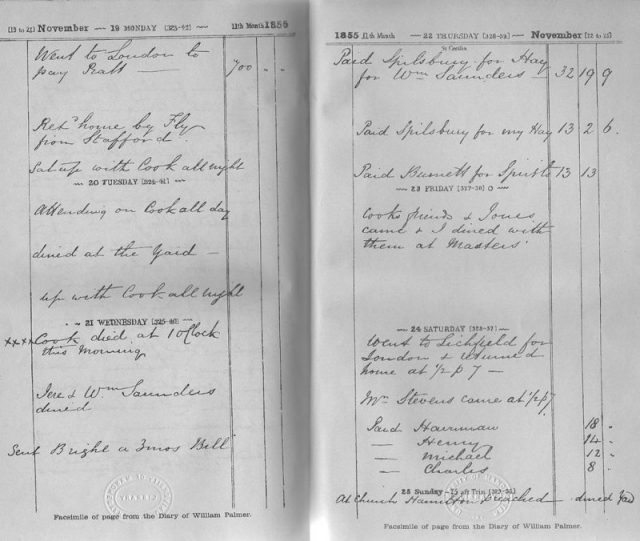

William Palmer was a well-respected and successful English doctor — with a penchant for administering poison for his own personal gain.

In 1847, the man who would be labeled the “Prince of Poisoners” married a wealthy lady by the name of Ann Thornton, the heiress to her parent’s hostelry, the Noah’s Ark Inn in Stafford.

Palmer was a notorious gambler, and he was very bad at it. Soon after the marriage, he began borrowing money from his mother-in-law, until she refused to lend any more.

Palmer was pretty sure that he would inherit a healthy amount from the old woman, but he needed more cash to fund his gambling addiction.

Struggling with debt and too eager to wait for Death to arrive in his own good time, Palmer allegedly took matters into his own hands. His mother-in-law is thought to have been the first victim in a string of deaths at the hands of the good doctor.

On the list of his suspected victims are a family friend who visited Palmer’s home and was probably poisoned shortly after; four of his own children who all died in their early infancy; and Ann Thornton herself, who was found dead at the age of only 27. Interestingly, Palmer had taken out a life insurance policy just a few weeks before his wife’s death.

Next to have his life insured was Palmer’s older and alcoholic brother, Walter, who very soon died from alcohol poisoning. This became the first suspicious death as the insurance company initiated an investigation.

By the time Palmer was convicted of the murder of John Parsons Cook, it is thought he had claimed the lives of at least 11 people, including his lover who bore him another child, as well as his best friend. Dr. William Palmer was hanged on June 14, 1856 before a spectacular crowd of 30,000 people. This was an early case in which investigators exhumed bodies to check for the presence of toxins, a case game-changer for forensics.

Choosing the wrong housekeeper cost her life

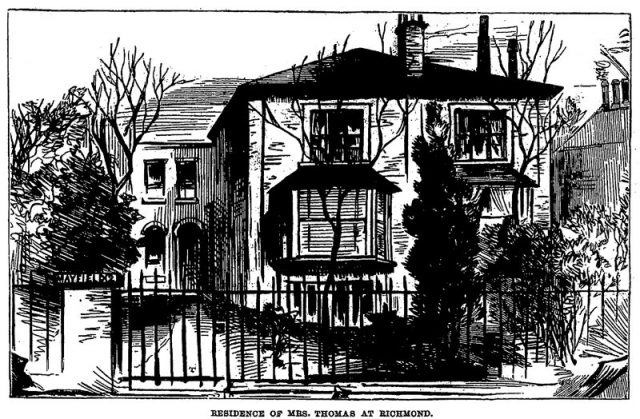

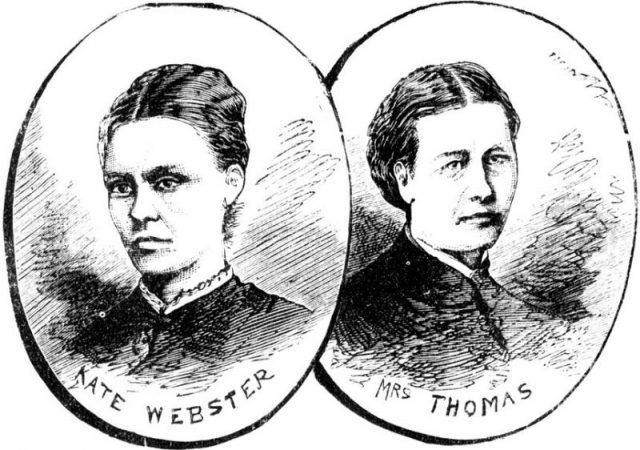

On January 29, 1879, a new maid calling herself Kate Webster started work for Julia Martha Thomas, a wealthy widower who lived in the affluent borough of Richmond (today part of Greater London). Mrs. Thomas would live just long enough to regret her choice of home-help.

Born Catherine Lawler in 1849 to a poor but respectable family in Killanne, County Wexford, Ireland, Kate’s greedy side was first exposed when she was caught stealing at the age of 15.

In her later teens, she sailed to England on stolen money, where she continued to rack up a lengthy criminal record over the years.

After discovering that pick-pocketing was not her forte, Kate started a new scam — she would rent a room, sell anything in the boarding house that wasn’t nailed down, and move on to the next place. Kate Webster was one of several aliases used by this callous woman.

Things started well, but within a month Kate was spending more time in the local public houses and neglecting her duties. Following a quarrel one Sunday morning, Webster gave Kate her marching orders, then left the house to attend church. When she returned, the housekeeper was lying in wait with an axe. She swiped the weapon at Mrs. Thomas’ head, pushed her down the stairs, and then strangled her, just to certain.

What she did next is gross, and scarily calculating. After butchering the widowers body on her own kitchen floor, her murderer boiled the flesh off the bones before packaging the unrecognizable remains into a crate. A local lad was paid to do the heavy lifting, and the remains of Julia Thomas were thrown into the River Thames.

After the mischief was managed, Kate Webster cleaned the house.

Assuming she was all clear, Webster stole her landlady’s identity and started selling off her personal belongings. A suspicious neighbor raised the alarm and, despite absconding back to Ireland, Kate was soon arrested for the gruesome crime. In the end, she confessed and was sent to the gallows. Regarding the body, everything except the skull was recovered.

The elusive skull eventually turned up in November 2010 during building works — in the backyard of Sir David Attenboroughs. Using carbon dating and other forensic methods, it was concluded to be the missing head of Mrs. Julia Martha Thomas.

You can’t marry that other woman

One day Mary Eleanor Wheeler Pearcey moved in with her lover Frank Hogg, but the two of them kept an unorthodox relationship: Both kept on seeing other lovers, too.

When Frank came home one day he informed Mary he planned to marry another woman — Phoebe Style, who was carrying his baby.

Mary Eleanor had a hard time accepting this, and she did so only after Frank promised to continue their relationship, even though he would be now married. A fragile peace was established.

On October 24, 1890, Mary called Phoebe and her infant over a cup of tea and “war” quickly broke out. The calm afternoon in the neighborhood was disturbed as odd noises and screams were heard from Mary’s place. After which the house fell morbidly silent.

Later that day, the body of a woman was found, hastily thrown on a trash heap in Hampstead, northwest London. The face of the victim was badly wounded and her throat was cut. A dead baby was found, too. The case was quickly linked with the earlier disturbance.

Read another story from us:The 5 Craziest Stories from the Prohibition Era

When police came to check, there were visible stains of blood everywhere. Asked by officers to explain the stains, Mary timidly said she was hunting rats. A few months later, the woman faced the same end as her own father, who had also been executed for murder.

Mary Eleanor Wheeler Pearcey is another character speculated to have been behind the Jack the Ripper crime spree.