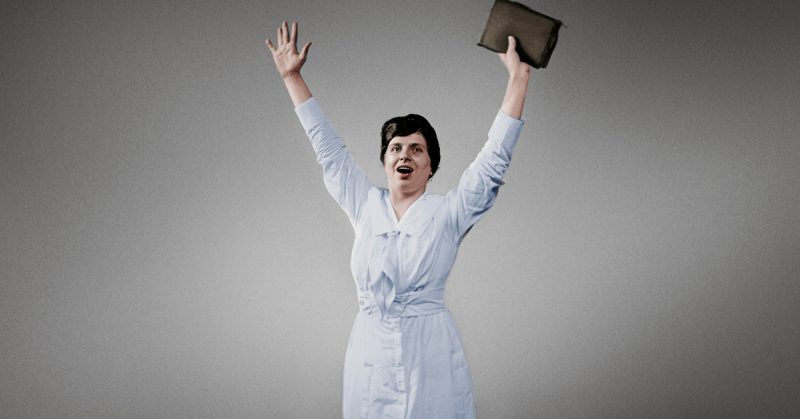

In the 1920s, Aimee Semple McPherson was a phenomenon — a bold celebrity, every bit as big as Greta Garbo, Harry Houdini, and Charles Lindbergh.

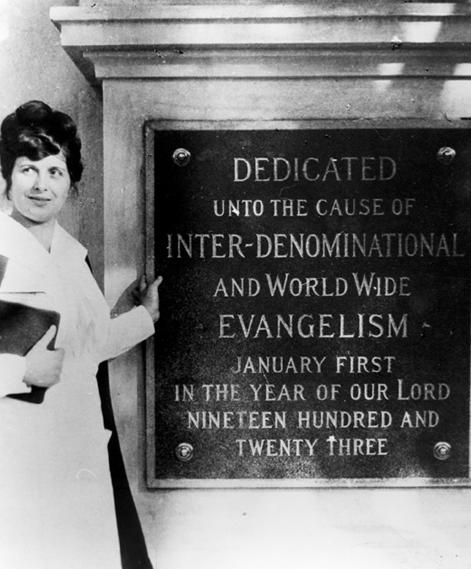

The evangelist, who established the Foursquare Gospel Church (which is still around today), had a passion for religion, a mind for business, and a definite flair for the dramatic, the likes of which have never been seen since (sorry Joel Osteen).

So when McPherson disappeared one May morning, in 1926, it became a “stop the presses” story that pushed President Calvin Coolidge off the front pages of newspapers nationwide.

It was at McPherson’s five-thousand seat church in Los Angeles, called Angelus Temple, where she made a name for herself.

Her Sunday sermons, which drew huge, enthusiastic crowds, were Broadway-like productions, complete with an orchestra and costumes.

Speaking in tongues and “healing” the sick and handicapped, McPherson brought followers to their feet, cheering. Word of her performances spread, and by 1926, McPherson had become a household name. And then it happened.

On May 18, 1926, McPherson, 34, mysteriously vanished from Ocean Park Beach, south of the Santa Monica Pier, during a swim.

In the days and weeks that followed, the faithful prayed for her safe return, while the Coast Guard patrolled the waters, looking for any sign of the missing evangelist.

Where was Sister Aimee? Rumors were rampant. Maybe she disappeared to have a secret abortion. Or perhaps she ran away with a lover. Others thought it was all just an elaborate publicity stunt.

The answer came about a month later, when McPherson returned in the most dramatic way possible: crawling through the desert to arrive at the Mexican town of Agua Prieta, Sonora, just south of the border with Arizona. McPherson was driven to a nearby hospital, and when she was strong enough to speak, she told her story. And it was as a doozy.

McPherson said that she went for a swim on Venice Beach and when she emerged from the surf a man and woman begged her to accompany them to their car to pray for their baby, who was desperately ill.

When McPherson approached the car, she was pushed inside and chloroformed. She would come to in a shack in the Mexican desert, tied to a chair.

Three Americans, including the two that lured her into the car, told McPherson that they were holding her for ransom for a half-million dollars.

If the church didn’t meet the demands, McPherson would be sold into white slavery. (In fact, the church leaders did receive a ransom note — make that multiple ransom notes — and handed them over to the authorities, who rejected them as hoaxes.) Eventually, McPherson was able to undo the ropes and ran away into the desert.

McPherson returned home to a hero’s welcome. It was quite a show. A crowd of more than 50,000 were at the train station to greet her. There was a parade in her honor and airplanes dropped roses from above. Los Angeles district attorney, Asa Keyes, was not amused.

He ordered an investigation into the evangelist’s “so-called” kidnapping. A few weeks later, McPherson found herself in front of a grand jury. Making matters worse, witnesses began to pop up claiming to have seen her in Northern California around the time of her abduction.

The most damning info of all: It seems that Kenneth Ormiston, a married engineer who worked at KFSG, the Christian radio station owned by McPherson’s church, disappeared around the same time that McPherson did and was spotted in the northern California town of Carmel with a mystery woman. (Ormiston would admit to having an affair at the time of McPherson’s disappearance, but denied that the evangelist was the woman he was rendezvousing with.)

Come fall the case was still making headlines when the district attorney charged McPherson with conspiracy and obstruction of justice. A trial was to take place the following January, but when it became clear that there wasn’t enough evidence to hold up in court, the charges were dropped. Good news for McPherson, but the district attorney’s U-turn didn’t stop tongues from wagging.

How curious, people thought, that McPherson and Ormiston would disappear at the same time.

But, others countered, if the two were having a clandestine affair, why would McPherson cover it up with such a far-fetched explanation? Put another way: The story was so bizarre, it had to be true.

Those in McPherson’s inner circle chose to believe her explanation (or, at least, claimed they did). It is a mystery that has never been solved.

McPherson stood by her kidnapping story, and Ormiston would never admit to being the evangelist’s lover. What’s more, there was no evidence linking the two.

Still, McPherson’s reputation took a hit. Many wondered why she didn’t insist on a trial to clear her name. Instead, she revealed the details of her abduction in a 1927 book, In the Service of the King: The Story of My Life — an ill-advised move that rubbed many the wrong way.

McPherson would spend the next several years trying to rebuild her ministry. In the mid-1930s, during the Great Depression, she went back to her “old-time” origins, mixing religion with charity work that targeted the poor, minorities included.

At the start of World War II, she would add a patriotic theme to her sermons. The crowds returned, making McPherson one of the country’s most popular ministers.

McPherson died on September 27, 1944 in Oakland, California, of a suspected accidental Seconal overdose. Though the Foursquare Gospel Church was thriving, and probably worth millions, McPherson had just $10,000 to her name at the time of her death.

Read another story from us: Only Known Recording of a Castrato – Italy’s Last Castrated Singing Boy

The International Church of the Foursquare Gospel Pentecostal denomination still exists with almost nine million members worldwide.