Maybe it’s the power, or the racy love life, or her striking looks (bangs, after all, are not easy to carry off).

But this much is clear: Cleopatra is one historical figure that we just can’t see to get enough of.

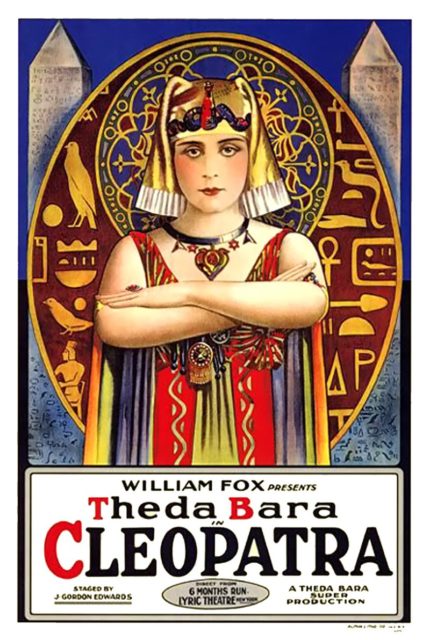

Hollywood has made no less than four worshipful big-screen movies and Stacy Schiff’s biography, Cleopatra: A Life, made The New York Times Best Seller list not too long ago — not to mention the number of women who don kohl eyes and trinkets each year to attend Halloween bashes as the Egyptian queen.

She was Egyptian

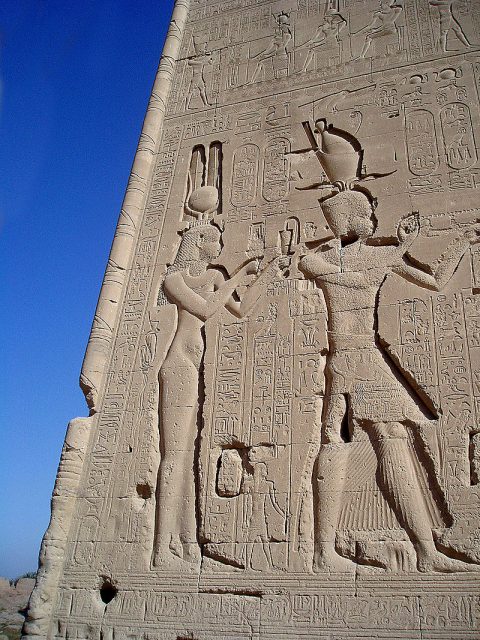

She may have been dubbed “Queen of the Nile,” but Cleopatra wasn’t Egyptian by birth. Though her family lived in Egypt for about three hundred years, Cleopatra’s roots could be traced back to the Greek Ptolemy I, who served under Alexander the Great.

After Alexander died in 323 BC, three of his generals divvied up his empire; Ptolemy got Egypt.

Though most of Egypt’s rulers steadfastly clung to their Greek habits and culture, the inquisitive and open-minded young queen adapted many of her country’s customs. In fact, she was the first member of her family to learn the Egyptian language — a smart move, which helped gain her people’s respect and trust.

She was drop-dead gorgeous

Yes, Cleopatra has been portrayed by some of the most gorgeous women in Hollywood (Vivian Leigh and Elizabeth Taylor among them). And true, legend has it that she managed to seduce the two most powerful men of her day: Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

But the queen wasn’t much of a looker. Coins from back in the day bearing her likeness show a woman with a sharp, jutting chin, a strong pointed nose, and a prominent forehead. Oh, and those bangs that Taylor and Leigh sported in their film bios? Also bogus.

Like most men, women, and even children of Egypt at the time, Cleopatra shaved her head. (Egyptians believed body hair was unclean, and, frankly, uncivilized.) In fact, she wore elaborate wigs made by slaves.

A much-favored coif: hair braided and pulled off the face into a tight bun wound at the nape of the neck, with short curls around her forehead.

That’s not to say she wasn’t irresistible in her own way. Ancient writer Plutarch claimed that while Cleopatra’s beauty was “not altogether incomparable,” it was her charisma (or, as he put it, “irresistible charm”) that made her desirable.

Take a closer look here:

https://youtu.be/xnRssdsGU8U

She was seriously superficial.

Many portrayals of Cleopatra depict the queen as a frivolous woman who dished out money like a drunken sailor — particularly when it came to beauty rituals.

Reportedly, she was fastidious about the way she looked and dipped into the nation’s treasury to maintain her grooming habits and lavish lifestyle.

But there was more to Cleopatra than kohl eyeliner, milk and honey baths, and henna tats. Make no mistake: This was one smart cookie. Though she got the throne at 17, she was well-educated and well-prepared to take over the reins.

She spoke (at least) a dozen languages, was well-versed in mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy. She also possessed a mastery of politics and warfare. She was even something of a feminist, giving Egyptian women rights, unlike other women of the day.

She was catnip to men

Yes and no. Oh, she was seductive all right. Consider the dramatic way she introduced herself to Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. In 48 BC, the resourceful Cleopatra, forbidden by her brother Ptolemy XIII to meet with the Roman general, had herself wrapped in a carpet (or, according to some historians, a linen sack) and smuggled into Caesar’s quarters.

Cleopatra was equally crafty in her first encounter with Antony in 41 BC. Ordered to appear before the general in Tarsus (in modern day Turkey), Cleopatra took her sweet time to get there, then arrived on a golden barge. All dolled up to resemble the goddess Aphrodite, the queen sat beneath a gilded canopy, while attendants dressed as cupids fanned her. In short, Antony was a goner.

She would go on to romance both men, but the relationships were as much about strategic maneuvering — on both sides — as they were about lust. Julius Caesar, in particular, had an eye on Egypt’s wealth, needing it to support expensive Roman battles.

Her relationship with Antony had a political component as well: Cleopatra needed him to protect her crown (he did so by killing her sister, Arsinoe, a rival to the throne). Antony, meanwhile, desired access to Egypt’s resources.

She killed herself because she was overcome by grief over the death of Antony

To be sure, the death of Antony devastated Cleopatra. But she didn’t have a lot to live for at that point: Egypt had fallen to Rome, and the once-proud queen was penniless and powerless, soon to be paraded through the streets of Rome as a trophy. She was not going to allow that to happen to her.

She died from an asp bite

Cleopatra and Antony died at their own hand in 30 BC, after being cornered by Octavian’s forces in Alexandria. Antony would impale himself with a sword, but the method of Cleopatra’s demise is in doubt.

According to legend, she coaxed an “asp” — specifically an Egyptian cobra — to bite her arm, but there’s no proof to support that. Poison, however, was most likely her method of choice. Some believe she pricked herself with a pin dipped into a lethal ointment. (She was known to conceal a poison in one of her hair combs.)

Read another story from us: The Forgotten Son of Caesar and Cleopatra

German historian Christoph Schaefer has offered yet another theory: The queen may have used a potent mixture of opium, hemlock, and wolfsbane — a potion likely tested on a few unfortunate souls to ensure it was pain-free.