Although a relatively unknown figure outside of Italy today, Gabriele D’Annunzio was an era-defining thinker, poet, aesthete and philanderer whose ideas inspired the political views of a young Benito Mussolini.

Even today in Italy, he remains a divisive figure, on the one hand, he is a prolific author who was admired by the likes of Puccini, Proust and Joyce, and on the other an almost perfect stereotype of an Italian lothario.

D’Annunzio was born in Pescara, Abruzzo, in 1863 to a family of privilege and good education. His father was a prosperous landowner and wine merchant who would become mayor of Pescara, giving D’Annunzio the opportunity to become university educated.

By the age of 16, D’Annunzio was showing signs of the extravagant self-promotion that would come to define his character.

D’Annunzio had, at the age of 16, published his first book of poetry and is very likely the source of the rumor that the author had tragically died.

The book was well received, and his subsequent works brought critical acclaim, D’Annunzio had become the darling of Italian literature.

With fame came rumours and while it’s unclear if D’Annunzio started them himself, he certainly did nothing to stop them, and throughout his life, he would neither confirm nor deny anything.

It was claimed that he had his bottom ribs removed to aid fellatio; it was alleged that he cooked and ate human flesh to see what it tasted like; it was claimed that he slept with every beautiful woman in Paris and that he made his housekeeper sleep with him three times a day.

He certainly used the power of his celebrity to further his own agenda, carefully crafting his image into something more than he was, he is famously quoted as saying “The world must be convinced that I am capable of anything.”

While he certainly had affairs with many women, he was not the most physically attractive man, once described by Liane de Pougy as “a frightful gnome with red-rimmed eyes and no eyelashes, no hair, greenish teeth, bad breath.”

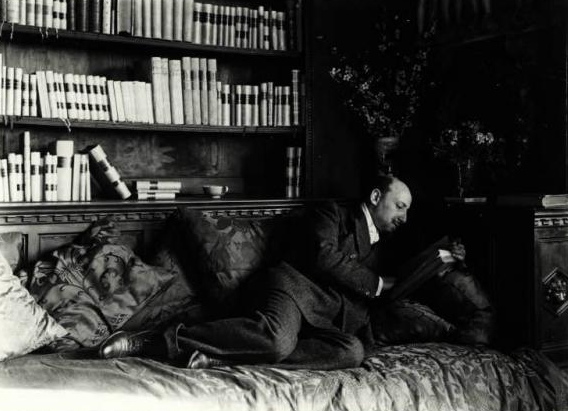

What D’Annunzio lacked in physicality he made up for in charisma and personality; he was always immaculately dressed and surrounded by luxury.

D’Annunzio could have stayed a flamboyant, Renaissance-style lord were it not for his extreme views on Italian nationalism. During World War I, he campaigned passionately for Italy to join, arguing that “a race only won respect by spilling the blood of its young.”

By all accounts, he was brave in battle and proved himself to be a more than competent aviator, becoming somewhat of a national war hero.

As the Treaty of Versailles was being signed, D’Annunzio convinced 2,000 of his fellow countrymen and women to march on the city of Fiume (designated as part of the new Yugoslavia now part of Croatia) and reclaim it for the Italian crown.

D’Annunzio ruled Fiume as de facto dictator for almost two years until the Italian navy laid siege to the town and D’Annunzio fled.

It was during the occupation of Fiume that D’Annunzio’s fascist ideas were crystallised. He maintained power through an SS style military force that he called the ‘Centurions of Death’, and he created the Charter of Carnaro for Fiume which stated, “Men will be divided into two races. To the superior race, which shall have risen by the pure energy of its will, all shall be permitted; to the lower, nothing or very little.”

Eventually, the intense pressure from the other nation states and D’Annunzio’s lack of political aplomb led to an end of the occupation and D’Annunzio headed back to Italy.

By now the seeds of fascism had been sown, and it was not long before Mussolini, imitating much of what D’Annunzio had created in Flume, laid siege to Rome and took over the government.

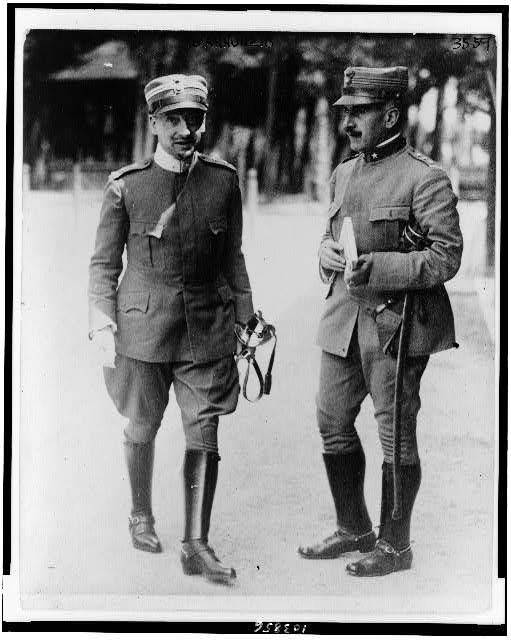

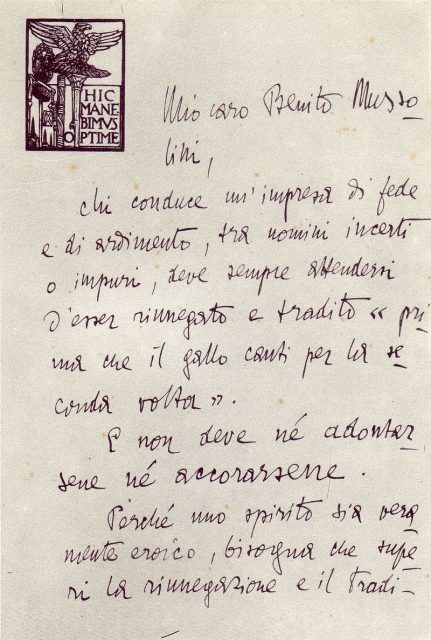

D’Annunzio and Mussolini were often pictured spending time together, but D’Annunzio was reportedly wary of the new dictator, and Mussolini saw D’Annunzio as a threat to his power.

Mussolini had learned well from the old maestro and, to create the image of camaraderie, lavished him with titles and extravagant gifts for his palatial Lombardy home, making sure to be frequently pictured with him.

Even his death in 1938 is shrouded in mystery. It is officially recorded as a stroke but according to legend, his girlfriend at the time was a Nazi spy who poisoned D’Annunzio because of his dislike for Adolf Hitler and the Axis alliance.

Read another story from us: Fascism in Italy – The Rise and Fall of Mussolini

Whatever the truth of his life, the ideas of Gabriele D’Annunzio have left an indelible mark on history, one that we are still trying to understand today.