We have all heard stories about weddings or funerals gone wrong. Maybe we have experienced something ourselves, but odds are you’ve (thankfully) never experienced something as horrifying as what happened at the funeral service for one of the greatest kings in history.

William the Conqueror (c.1028-1087), sometimes known as “William the Bastard” (definitely not to his face), was the feudal lord of Normandy who conquered England in 1066, the last time the island nation was subjugated by a foreign foe.

William, the illegitimate son of Duke Robert I and a tanner’s daughter named Herleva, was descended on his father’s side from Rollo, the Norwegian Viking who was given Normandy by the King of France in return for defending France against his pagan brethren.

Rollo’s descendants, including William, may have converted to Christianity, but they were just as fierce and lusty as their Viking forefathers.

William, in particular, was reputed to have both a fierce temper and a fierce appetite. Both of these traits would leave him essentially without mourners when he died.

Of course, William the Conqueror is hardly the nickname of a timid man or a man without enemies. Though he was “legitimized” by the Church and had become the sole ruler of Normandy by 1047, and had made it the strongest territory in France and essentially a nation unto itself, William’s ambitions came to include becoming King of England as well.

His claim to the English throne was a bit tenuous: he was a distant cousin to the English king, Edward the Confessor. Aside from the ties of blood, Edward had spent time in exile in Normandy as a young man, after having been run out of England by the Danish warrior king Canute, who briefly united the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and England.

Edward returned to England upon the death of Canute and ascended the throne with a special place for Normandy in his heart.

In 1051, the childless Edward invited young William to his court and reportedly promised William the throne when he died. William never forgot that promise – not for a second.

However, in the time between 1051 and 1066, Harold Godwinson, the scion of a noble and powerful family and accomplished warrior, had become Edward the Confessor’s brother in law, and was the Earl of Wessex, a powerful position.

Harold and his supporters claimed that he was promised the English throne by Edward on his deathbed. The king’s advisers, called the “Witan” or “Witanegemot,” gave Harold the necessary support and he was crowned in January 1066.

Another claimant to the throne was the legendary Viking warrior Harald Hardrada (or “Hard-ruler”). He claimed the throne of England through Canute the Great.

William dismissed both of these claims. The Norwegian claim was based on a line of kings that didn’t exist anymore. Harold’s claim? Well, that was a different story. In 1064, Harold shipwrecked on the Brittany coast of France, a neighboring and rival duchy of Normandy. Threatening Brittany’s lord Conan II with invasion, William demanded Harold be handed over – William knew he was a valuable hostage, and that his family would pay a huge ransom to set him free. That, or William could extract valuable oaths to do so.

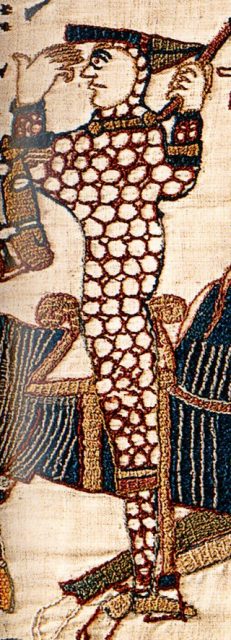

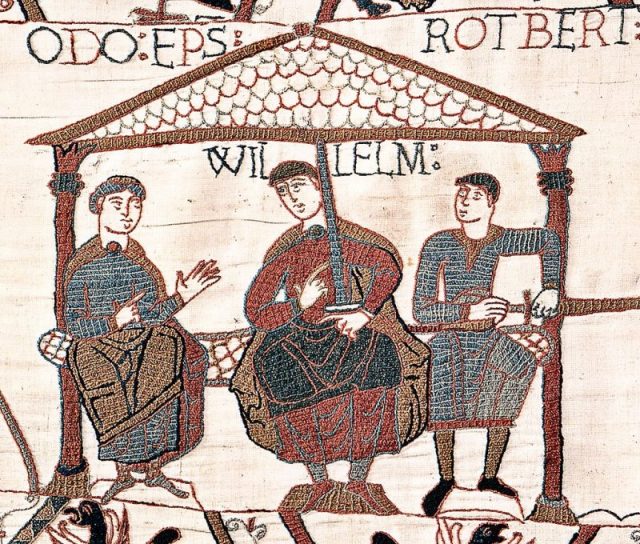

By all accounts (including an illustrated chapter of the famed Bayeux Tapestry), William and Harold got along well – hostage-taking was a regular practice, and noble “guests” were mostly treated with respect and hospitality.

Harold even went on campaign with William and reportedly saved the life of two Norman knights stuck in quicksand. In the Tapestry, Harold can be seen pledging to William – that pledge was to honor William’s claim on the English throne. So, when Harold took that throne, William and his Norman knights took him for an oath-breaker, the worst kind of liar there was, and vowed vengeance.

Before William could assemble his fleet and army, Harald Hardrada invaded northern England in September. On September 25th, King Harold defeated the Vikings at Stamford Bridge.

It was there that Harold received word that the Normans had landed on England’s southern coast. Racing the length of England, Harold met William at Hastings, about 65 miles south of London. As history records, William was victorious and Harold lay on the field, dead from an arrow taken in the eye.

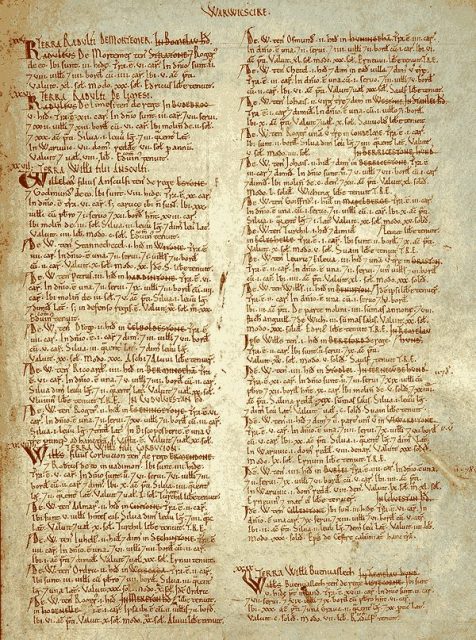

Over the course of the rest of his lifetime, William consolidated his hold over England. It was a long and brutal affair, marked by oppression, slaughter and the almost complete suppression of Anglo-Saxon culture.

Norman French blended with Anglo-Saxon Old English to begin to form the modern English language. Behind all of this was William, who met any opposition with utter ruthlessness.

Along the way, William enjoyed the fruits of his conquest. And the meats. And the ales. He grew immensely fat, and his death was caused when the pommel of his saddle was literally driven into his intestines, puncturing them. The medical men of the time were not able to do anything to help him and he lingered in immense pain for six weeks.

He died in Normandy and his heirs left it to medical men (the term is relative) to deal with the body of the feared but unloved king. The corpse had lain in a surgical facility in Rouen for some days before a passing knight had him embalmed out of duty to his lord.

However, decomposition had already set in and the embalming was hardly complete – and there was still an ad-hoc funeral to be held in Caen, the family seat, some seventy miles away.

Already in a decrepit state, William’s body suffered further indignities when a fire broke out in the city. Days more went by. Then, a man challenged the local church where his body lay, claiming it had been built on his land.

By the time this all was settled, weeks had gone by. Though William’s body was wrapped in funeral sheets, it still stank and had bloated up to many times its natural size, which was already large.

When the gravediggers went to lower the body, it would not fit in the hole. So they attempted to cram it in. That’s when William I, ruler of Normandy and King of England, exploded. His body rained down on what mourners there were, and a horrible stench filled the air.

People got sick, making a bad situation worse. Others passed out. Most ran away in terror. Finally, what remained of William was dumped in the hole and hastily covered up. That was the last resting place of one of history’s most famous figures.