In the early 1900s, it was still unusual for African-Americans to become successful entrepreneurs. While slavery was abolished after the introduction of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, there was still very little opportunity for black people to obtain financial security in areas outside of agriculture.

When it came to women, the opportunities were nearly non-existent. However, the poor odds didn’t stop black women to work tirelessly on achieving their goals, shaping history and fighting prejudice along the way.

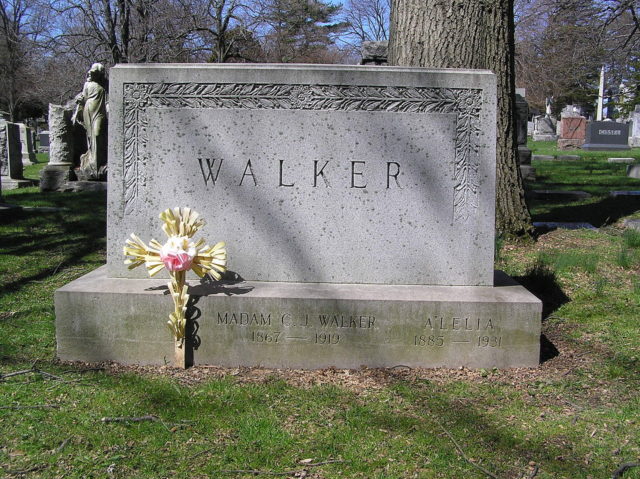

Among those great women was Madam C.J. Walker who managed to build an empire from scratch based on her hair products. A daughter of freed slaves herself, she was born in Delta, Louisianna, in 1867, under the name of Sarah Breedlove.

She would adopt her alias C.J. Walker, together with the title of “Madam,” later on in her life, after years of hard labor, both on the plantation on which she grew up and in a St. Louis laundry where she moved in 1888 following her first marriage.

You could say Breedlove struggled from day one ― born in a family of six children, she lost her parents around the time she was seven. At the age of fourteen, she was already married. By the time she moved to St. Louis, she was 20, had a three-year-old daughter, an ex-husband and not a dollar in her pocket.

For the next 18 years, she would work as a laundress, earning just enough to get by. In the meantime, Breedlove learned to read and write with the help of a local church, while struggling to provide her daughter with a formal education.

By the time she was in her late thirties, years of hardship and mistreatment had caused her hair to start falling out. Driven by fear of losing hair, Sarah Breedlove started examining cosmetic products sold at the time, meticulously examining their content.

Breedlove began making her own remedies based on existing products, while at the same time working as a sales agent for another self-made black woman in the industry ― Annie Minerva Turnbo Malone ― whose company was already booming.

Around 1905 she moved to Denver and married Charles “C.J.” Joseph Walker, a newspaper ad salesman, who supported her efforts to kick-start a hair product company. Sarah Breedlove adopted her husband’s name, adding the title Madam as a reference to a number of popular French female fashion designers and beauty industry moguls.

According to her official biography, Madam Walker once attributed the success of her formula to a dream she had, in which a tall African man gave her the ingredients for her hair-growing recipe.

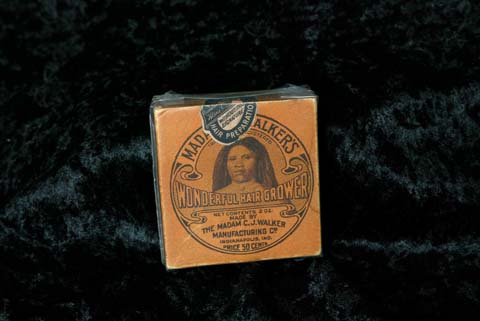

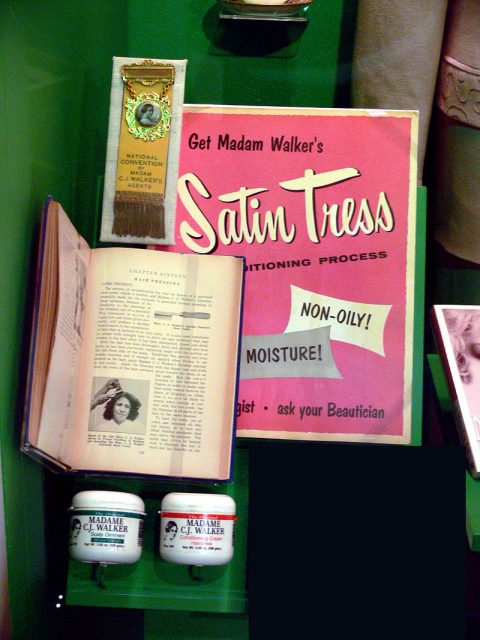

Some of these ingredients were plants which grow exclusively in Africa, but that didn’t stop her from acquiring them. Thus, the legend of “The Wonderful Hair Grower” was born. It was the first in the line of her Black Hair Products, all of which found a great response with African-American communities. But her contribution didn’t end there ― her products were redefining beauty on a nationwide scale.

While the standard of the time excluded black people, considering white females as the epitome for beauty, C.J. Walker’s products created a counterweight to that vision. However, like everything in her life, it didn’t come about by itself.

She worked day and night creating a network of clients, many of whom were part of various church groups and clubs. She ran ads in African-American newspapers across the country and was very soon rivaling her old mentor, Annie Malone, who even accused Walker of plagiarizing her own formula for the hair grower.

The argument between the two women is still a subject of debate, as Walker is today often cited as America’s first African-American female millionaire, while, in fact, it was Malone who first achieved the status.

Nevertheless, Walker’s business blossomed in the 1910s. She constantly participated in charity events and offered help for the less fortunate, such as providing scholarships for students. Walker also supported various civil rights causes to support the empowerment of black women across the United States.

Besides her wealth, Madam Walker earned respect, partly due to her appearance in the 1912 National Negro Business League convention. Although uninvited, she took the stage and gave an inspiring speech, forcing the all-male business league to recognize her efforts:

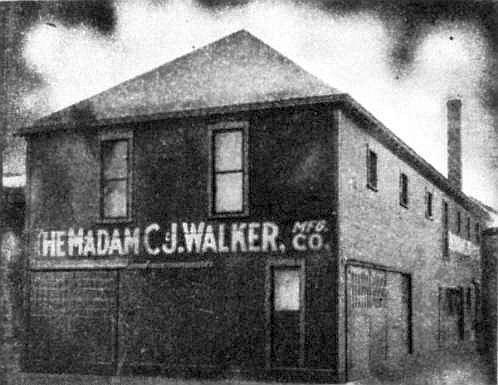

“Surely you are not going to shut the door in my face. I am a woman that came from the cotton fields of the South. I was promoted from there to the wash-tub; then I was promoted to the cook kitchen, and from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

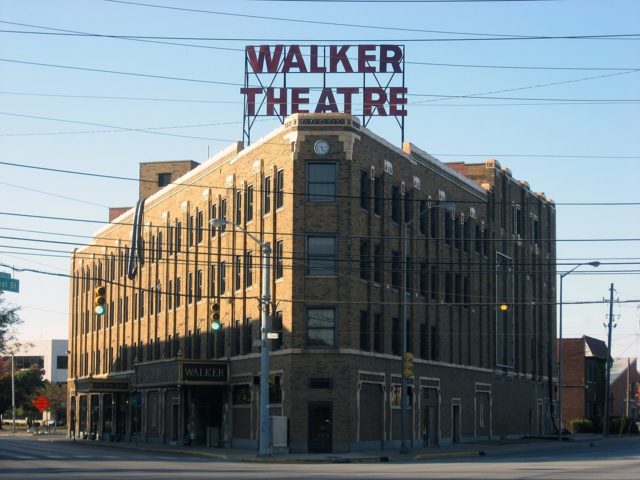

By 1916, she had amassed enough wealth to purchase a four-acre estate in the same New York neighborhood where John D. Rockefeller lived. Walker commissioned Vertner Woodson Tandy, one of the first African-American architects in the country, to design her mansion.

Walker had a habit of driving her fast cars at high speeds around the esteemed New York neighborhood, driving her snobbish and uptight white neighbors mad. For them she wasn’t only a black woman, she was “new money” as well ― a self-made woman opposed to their industrial empires and dynasties.

Less than a year after moving into her lavish mansion, Sarah Breedlove aka Madam C.J. Walker died from kidney failure on May 25, 1919.

Read another story from us: African American Cowboys in the Wild West

Her legacy set the scale for the future of beauty industry, lifted many black women out of poverty and challenged the way black people were perceived ― especially in the Southern States ― during an age of segregation, racial violence, and bigotry.