In the long history of the English monarchy, there have been sixty-six kings and queens that have ruled the island nation and empire.

Beginning with the fall of the Roman Empire and the dissolution of Roman rule in Britain, only one of those monarchs has been given the appellation “the Great”.

This was Alfred, King of the West Saxons, and eventual king of much of England. When people think of kings, especially those of antiquity, the first image that pops into their minds is usually one of a robust, ultra-masculine figure ready to draw his sword at a moments’ notice or slight.

For sure, England has seen its share of those kings – three examples come readily to mind: William of Normandy, dubbed, “the Conqueror”, Richard I, called “Lionheart”, and Henry VIII, whose very name stood for his womanizing, jousting and harsh yet in many ways enlightened rule.

All of these men cut a big, bold figure, but none of them is known to history as “The Great” – that belongs to Alfred. Though one could argue that Cnut I of Scandinavia, who ruled a unified English, Danish and Norwegian kingdom from 1017-1035 had also been called “the Great”, Alfred was the only native-born English king given the name.

He was born at a time when Englishmen were divided, not only among themselves but by the fierce Viking warrior bands that came from Scandinavia to raid and conquer. At the time of Alfred’s birth in 849, England was far from a united kingdom. Alfred’s father Æthelwulf sat on the throne of Wessex in the south, Beorhtwulf sat on the throne of Mercia in the northwest, and a series of three kings sat on the throne of East Anglia during Alfred’s early years, until taken by the Vikings.

Recently, a variety of TV dramas have given us a somewhat flawed vision of Alfred’s rise to power. The fact of the matter is much more straight-forward than the political maneuvering seen on TV. Reality also dismisses the idea that Alfred was the child of anyone but his acknowledged father, Æthelwulf, son of Ecbert, also depicted on TV.

When Æthelwulf died, the two eldest of his five sons became kings: Æthelstan became king of Kent, and Æthelbald, the king of Wessex. Upon the death Æthelbald, his crown fell to another brother, Æthelberht. When this brother in turn died shortly thereafter, the next youngest, Æthelred became king.

It was then the young Alfred, who at the time was only sixteen, was named “Secundus” by the most powerful bishop of England. This was to designate Alfred, the last of the line, as king upon Æthelred’s death, despite Æthelred having sons. In 871, die he did, and Alfred, age 22, became “King of the West Saxons”.

Other than the fact of his royal birth, nothing about Alfred said “king”. He was sickly, afflicted with a gastrointestinal disorder that forced him to limit his diet to milk, water, vegetables, and porridge.

Today, many medical historians believe that Alfred was a victim of Crohn’s Disease. By all accounts, Alfred would from time to time rebel against this diet, eat meat and ale – then suffer crushing abdominal pain for days. Despite this, however, he continued in his duties, and most of his contemporaries knew they were witnessing something special – Alfred was a man of iron will.

Alfred was also exceedingly smart and learned. While his four older brothers were burdened with ruling, Alfred was able to study. As a child, he and one of his older brothers had been sent to the court of Pope Leo IV and exposed to the world, and to Latin.

Upon his return to England, Alfred learned to speak other languages and read widely of science, religion and the Classics. During his reign, Alfred was a tireless advocate of expanding education in his kingdom, sometimes irritating the Church with his demands that education be conducted in the national language rather than Latin.

Though Alfred was an advocate for education and other changes to both English government and society during his life, his reign (especially his early reign) was focused on one problem – the Vikings.

The Viking raids had begun with the sacking of Lindisfarne in 793, seventy-eight years prior, but for many years they were few and far between and while extremely bothersome and costly, did not present a deadly threat to the kingdoms of England.

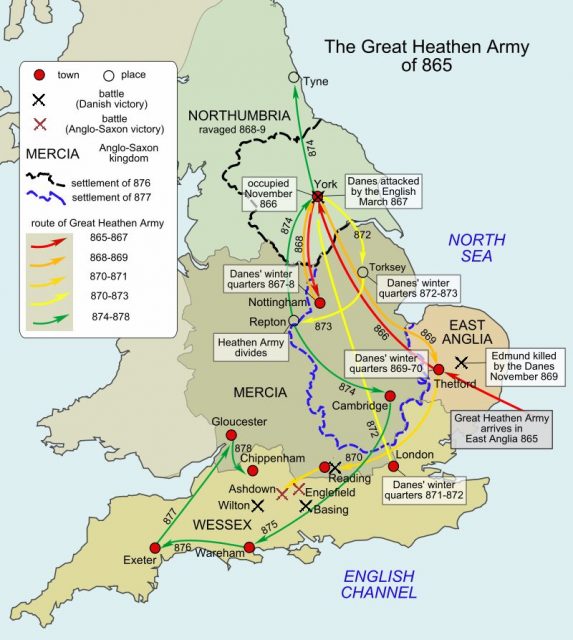

During Æthelwulf’s time, the raids had become larger and more permanent, and though the English did inflict serious defeats on the Vikings from time to time, by the time of Alfred’s reign, the Norsemen were well established in the north and east of the country, and were the most important issue facing the young king.

Shortly after taking the throne, Alfred went to battle with the foreign invaders. The first two battles fought during Alfred’s reign were defeats: one while he was attending his brother’s funeral, and another in his presence.

He was forced to bribe the Vikings with a sizable payoff, and though a relative peace existed for the next few years, everybody knew that it was only a matter of time before war would begin again, for this payoff did not mean that the Vikings left England, just that they would not attack Alfred.

In 876, a new Viking chieftain, Guthrum, attacked Alfred’s kingdom. After a couple of inconclusive battles, the Vikings took payment and swore to not attack again – an oath which they broke. This period is marked both by victory and defeat for Alfred.

On the one hand, he defeated the Viking fleet when they attacked Devon, but was surprised by the Vikings at Chippenham, a royal seat, and was forced to flee into the local marshes to avoid capture.

It is in these marshes that Alfred’s legend really begins. A famous tale (perhaps true, perhaps not) tells of Alfred sitting by the fire in a peasant woman’s hut, tasked with making sure the bread on the fire didn’t burn.

Thinking too much of his problems, the cakes burnt and Alfred was roundly chastised by the woman whose house he was forced to shelter in. This tale was told to show not only how far Alfred had fallen, but also his humility.

While in the marshes, Alfred and his men conducted raids against local Viking forces and kept the idea of a Saxon kingdom alive – the other Saxon kingdoms of Northumberland and East Anglia were now in pagan hands.

However, while the Vikings were looking for him and while they were busy plundering and ruling the other parts of England, Alfred was both solidifying his rule (such as it was) and raising an army.

According to contemporary sources, Alfred’s personality and willpower were so strong that he commanded a fierce loyalty, and while he was hiding in the marshes, he sent his nobles into the land to raise an army, both in the areas under nominal Viking control and those still ostensibly Saxon.

At the battle of Edington (or “Ethandun” in Old English) in 878, Alfred inflicted a serious defeat on Guthrum and his Vikings. As a result, Guthrum and many of his leading men agreed to convert to Christianity, and rule in East Anglia in Alfred’s name.

Though the Vikings in East Anglia would from time to time break their oath and raid nearby communities in Wessex, it appears that this was done without the permission of Guthrum, who seems to have been at least mostly loyal to his oath until his death in about 890.

The treaty between Alfred and Guthrum also included the stipulation that Mercia (formerly one of the most powerful English kingdoms) be divided between Alfred and the Vikings. In this, Alfred was the winner – the Vikings had controlled all of Mercia before the treaty.

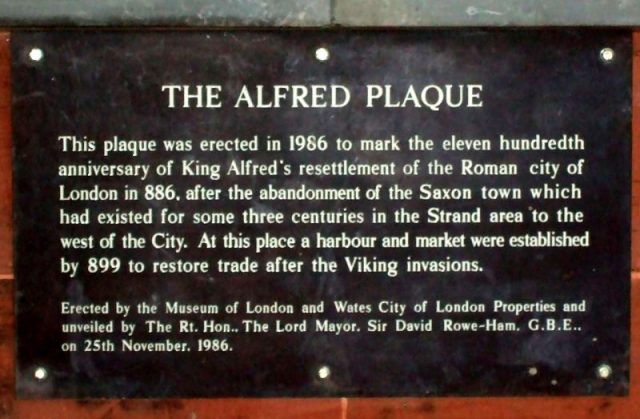

Despite these achievements, Alfred still had the Vikings of northern England (and their Scandinavian reinforcements) to deal with. To help contend with these forces, Alfred began to fortify the lands under his control. He constructed strong-points known as “burhs” – these strong-points were sometimes already cities or small settlements and grew under Alfred’s protection.

Fortunately for Alfred, England was one of the most blessed of kingdom’s in terms of resources and trade, and this enabled him to build burhs and a network of roads connecting them throughout his kingdom. Think of it as a kind of “pony express” for defense and communication – and Alfred’s system of defense stymied further Viking inroads into his lands. This defense system also improved trade and paid for itself many times over.

Many historians credit Alfred with being the “Father of the English Navy”. This is misleading. His grandfather had constructed a small fleet of warships and had used them at times, but Alfred built ships based on the Roman and Greek models, which were actually larger than most Viking ships.

Though he did construct about sixty of these ships over the course of his reign, they were unfortunately too big for the river systems of England, where the Vikings long-ships were dominant. However, they did allow Alfred to move troops from one part of the country to the other more rapidly than before.

While dealing with all of these problems and issues, Alfred also decided that the Anglo-Saxon law system needed reform. For the most part, this meant the codification, or writing down, of the laws that existed in the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Alfred also included laws based on the Ten Commandments and the New Testament as part of the official law of the land.

Read another story from us: The True Story of Robert the Bruce – Scotland’s Legendary King

By the time of his death in the fall of 899, Alfred was the recognized ruler of all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms not under the control of the Vikings (this meant Northumberland surrounding York). He is venerated in the Catholic Church as a “Defender of the Faith”, and is universally recognized as the man who prevented England from being conquered by the Vikings.

His son Edward the Elder took the throne after a brief family struggle and ruled until 924.