As a female reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth I of England cared deeply about her image. She sat on the throne of England from November 17, 1558 until March 24, 1603, but according to one wild conspiracy theory, for all of those years, it was not a woman acting as ruler of the kingdom, but a man in disguise.

The conspiracy is recorded as the “Bisley Boy” and claims that King Henry VIII, the father of the Virgin Queen, was so well deceived by his courtiers that he didn’t even recognize his own daughter had been swapped with another person. More than that, if we believe the story, then over four centuries of British royal family history are founded on a big, fat lie.

According to the story, when Elizabeth was just 10-years-old, she was sent away in the village of Bisley, in Gloucester, to avoid the outbreak of Bubonic Plague which ravaged the city of London.

The royal family deemed that far from the capital where the plague concentrated, the young princess would be safer. At that point, Elizabeth was not first in line to the throne but was still very precious to the King.

He had wanted her to marry a prince from a foreign kingdom as was customary, perhaps Spain or France, to strengthen relationships between the countries.

But, as this story goes on, something terrible happened to Elizabeth anyway: She succumbed to the illness and died. The tragedy caused great panic among the courtiers. Her governess Lady Kat Ashley and guardian Sir Thomas Parry tried to conceal the death.

Just shortly after the death, King Henry VIII was scheduled to arrive from London and see his daughter. He was not informed of the devastating news, and those who had been charged with the princess’ care conspired that he never would be.

Afraid that he would be angry and immediately order their execution, they were quick to devise a plan.

They buried the body somewhere close to the house and went searching for an imposter in the village, the tale continues. There wasn’t a single girl in Bisley that had flame-red hair or with a similar physique to Elizabeth, however there was one candidate: a boy called Neville.

The boy donned a wig and the dress of his now late friend, and was presented by Lady Ashley and Sir Parry as princess Elizabeth.

The deception did the trick and the young boy stoically continued his acting role as the offspring of King Henry VIII and his second spouse Anne Boleyn. “She” eventually inherited the throne and reigned over England in its Golden Age, famously defeating the Spanish Armada, yet failing to continue the line with their own child.

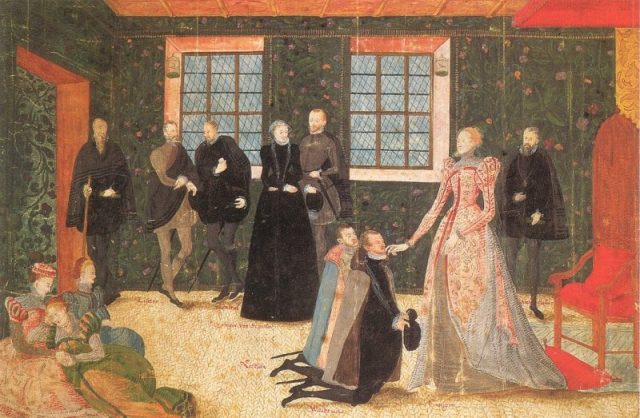

While this story works great as a piece of fiction, one or two historians and writers have chosen to give it credibility anyway. In fact, various clues have been highlighted to confirm the theory’s authenticity, beginning with why Elizabeth I was so careful to craft her appearance, always controlling the manner which her portraits were done by painters or the way she looked outside the royal quarters.

For instance, the queen always wore wigs regardless of what the occasion was. Nobody was ever allowed to see her without wearing one.

Supporters of this crazy theory also exploit some of the biographical facts about Queen Elizabeth I. She indeed never accepted a marriage proposal, despite offers from everywhere around Europe, including Russia and its infamous Tsar Ivan the Terrible, insisting that she was wedded to her country.

That Elizabeth I never had a child, or that she forbade an autopsy after her death, have been taken as additional arguments by conspiracists that the Queen was just trying to protect her secret.

Added to this are some of the Queen’s bold statements, such as her declaration: “I have the heart of a man, not a woman, and I am not afraid of anything.”

The last Tudor monarch also kept close ties with Lady Kat Ashley and Sir Thomas Parry, close enough that some people wondered about their connection. The nobleman Sir Robert Tyrwhitt would note in 1589 that he was certain Lady Ashley and Thomas Parry had a secret, and that “there’s a pact between them to take that secret to the grave.”

Shortly after the coronation, Elizabeth hired Lady Ashley as her main bedchamber attendant, the sole assistant who would help her (or him) with the dressing and undressing of those huge, elaborate frocks, which would have been more than capable of concealing any masculine feature.

Lady Ashley would have also assisted the queen with her heavily applied white makeup, especially useful with the always growing beard of a man.

Sir Parry was also well acknowledged by the court of Elizabeth. Following the coronation, he acted as the Queen’s Privy Counsellor and held few other prominent offices within the royal family. He was also knighted.

This entire bizarre Queen Elizabeth I cross-gender story would most likely have been forgotten if it wasn’t for one notable 19th century author — Bram Stoker, famous for his cult Gothic novel Dracula.

In his book Famous Imposters, Stoker recounts a story of a coffin that was discovered in Bisley, close to the house where the 10-year-old Elizabeth was once brought during the plague epidemic. Inside the coffin were the remains of a young girl, who judging from the lavish clothes and jewelry she was dressed in, belonged to an elite family who lived sometime in the Renaissance era.

“All honour to her whosoever she may have been, boy or girl matters not,” he wrote at the end of the chapter dedicated to evidence of Queen Elizabeth I’s possible hidden gender.

Read another story from us: The Cross-Dressing French Aristocrat Who Became an Elite Royal Spy

Regardless, the factual evidence is more than abundant that Elizabeth I was a woman. She often wore dresses which clearly emphasized her feminine features such as her breasts. More accounts even testify that she had regular cycles of menstruation…which pretty sums up what was hidden in the monarch’s pants.