In the fall of 2016, a Danish couple found a pre-Viking Bronze Age sword while metal detecting near their home in rural Denmark. Last year, hunters in Norway found a Viking sword simply sticking out of some rocks where a glacier had receded.

Just a couple of months ago, a little Swedish-American girl found a Bronze Age sword while swimming in a Swedish lake. That covers Scandinavia, home of the Vikings and their fierce Bronze Age predecessors – cool and unusual, but not completely unexpected.

But this week it was announced that another Viking sword has been found – this time in…Turkey. Actually, if you know history, it’s a bit less dramatic than it sounds, but still, finding a Viking sword in Turkey is rare – in the extreme.

A Viking presence in what became modern-day Turkey has been known for centuries, but think of what may have walked over that sword: Byzantines, Crusaders, Ottomans, trading caravans heading for the Far East…the list goes on into the modern era, when many wars were fought in Turkey, both between internal foes and with the enemies of the Turks – Greeks, Russians…through all of that, a Viking sword rested in the soil undisturbed.

The sword was found in the southern Turkish city of Patara, a quiet resort town about 150 miles from the nearest large city, Antalya, and 62 miles from the famous Greek island of Rhodes. It is a resort town, but it is quiet and has so far avoided the congestion and overcrowding of the rest of the Mediterranean coast.

It’s a beautiful location – but not one often associated with a Viking long-ship, and perhaps the sword didn’t get there by ship at all, but after a long march.

As we know, the Vikings were great explorers. Most of us are familiar with their voyages across the North Sea to today’s United Kingdom, Iceland, Greenland and the coast of Newfoundland, but the Vikings sailed much further afield than that.

While the Norse (a word used to describe the Vikings from Norway, and sometimes generically) and the Danes were raiding Western Europe and the North Atlantic and into the Western Mediterranean, the Swedes were establishing a huge and rich trading empire on the coasts of Eastern Europe, and throughout the river systems of Russia.

Many historians and etymologists believe the word “Russia” comes from the Slavic word “Rus,” used to describe the red hair and ruddy complexions of the Swedes, who came to rule over much of Russia in the years before Vladimir the Great (1015), the ruler who converted the Russians to Christianity, and who was of Viking stock himself. The Swedes established great trading stations along the Volga River and the Russian coast of the Black Sea.

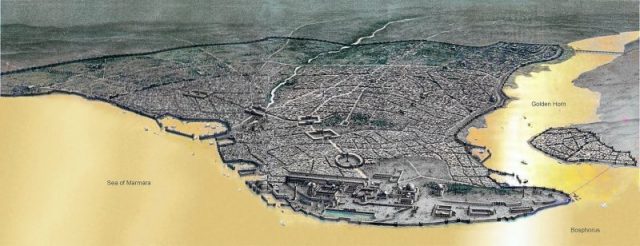

So, when we look at the extent of Viking travel, we see that much of Europe was visited, raided or ruled by the Vikings. Seen that way, it’s not really a surprise to find a Viking sword in Turkey, because goal number one on many Viking lists was making it to the greatest city of the medieval world – Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine, or Eastern Roman empire. Today’s Istanbul.

Constantinople was the richest city in Europe, and obviously the stuff of dreams for any greedy Viking. However, the city was too far and much too strong for any Viking raiders to take, or even raid successfully, so the next best thing was to establish trade, which many Vikings did over the years.

The Byzantines were at the center of the world at the time, and they were more than familiar with the warriors from Scandinavia. The Byzantine emperors even offered many of them a place in the army.

These became the “Varangian Guard” for the emperor and his family, and were the elite shock troops of the emperor’s army. “Varangian” likely comes from the Norse word “to pledge” — warriors pledged that they would serve a certain amount of time.

For a Viking, a place in the Varangian Guard was a dream come true – riches, the run of the place, and access to more food, women, and drink than were in Valhalla. It wasn’t just Swedes who worked for the Byzantine emperor – word got around and many Norsemen and Danes also volunteered.

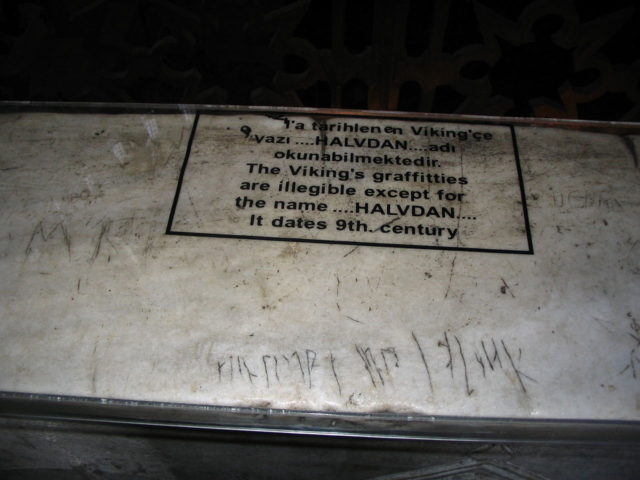

Two of them were “Halfdan” and “Ári”. We know their names because they left them to be found in two runic inscriptions. You can see them today if you visit the famous Hagia Sophia, the beautiful mosque in Istanbul, once an Orthodox church.

On a balcony on the south side, you can read “Halfdan carved these runes.” Not far away, a man named Ári wrote: “Ári made the runes.” Aside from Ári and Halfdan, we know that the famous Norwegian Viking and later king, Harald Hardrada (“Hard-ruler”), was a member of the Varangian Guard and took part in many battles on behalf of the emperor.

Harald later returned to Norway, seized power, and after some years, attempted to restore Viking rule to northern England, but was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.

The Turkish city of Patara is ancient, and once was of great import as a trading post with the rest of the Mediterranean world. Archaeologists have been digging there for over thirty years, finding items spanning the period from the Greeks to the 19th century. The sword is of Scandinavian design. The intact part is 17 inches long and was found inside a wooden sheath, which is of great importance.

Viking swords in wooden sheaths have mostly been found in graves: Vikings, like many other cultures of the time and before, left grave goods to journey to the afterlife with the departed.

Read another story from us: 8-yr-old Girl Finds Ancient Pre-Viking Sword in Swedish Lake

The sword has been dated to the 9th or 10th century, just as the Viking influence was beginning to be felt in the area. Digging continues and there are hopes that other Viking objects may be found.