“Criminals,” explained Batman in his 1939 first appearance, “are a superstitious, cowardly lot.”

The Dark Knight Detective didn’t know the half of it.

In 1935 a gnarled human hand was donated to the town museum in Whitby. A faded fishing port in North Yorkshire, Whitby is best known for inspiring one of its best known visitors — Bram Stoker — in the composition of his landmark work of gothic horror, Dracula.

This mummified hand had been found in the late 1800s hidden above the door frame of an old thatched cottage in Castleton, a village deep in the North York Moors.

The cottage had previously belonged to a local rogue, although he was never convicted of any crime, and this disgusting discovery was instantly recognized as the Hand of Glory.

It was and still is, the only surviving example of its kind. The house’s new owner was tempted to rebury it in the village cemetery, but instead passed it onto a local historian who eventually donated it to Whitby Museum.

An old thieves’ charm, the Hand of Glory or Dead Man’s Candle, was just one of the many by-products of the gallows.

Once night fell, those condemned criminals — preferably murderers — who were publicly hanged found that their indignity wasn’t over.

Their dangling body was hacked up for various purposes by the desperate and the despicable alike.

By special permission surgeons carted them away for public dissections, but they were an honest exception.

Splinters of the gallows were taken as protective or healing charms (or popped in the mouth to ease toothache); the rope itself was said to cure headaches; teeth were prised out for the making of dentures; and various stomach-turning folk medicines called for human fat, blood and the moss growing on the skull of a hanged man.

The most potent of the hanged man’s body parts, however, were his hands. Across the 18th century there are reports the sick lining up to place their withered limbs, or even their sickly babies, into the lifeless hands of a hanged man, often the executioner himself would charge a small fee for access to the corpse.

Hardened criminals, though, had a far more nefarious and gruesome use in mind for the dead man’s digits.

The cadaver’s right hand was cut off, it was drained of all blood and wrapped in a burial shroud with which to draw out the last drops of ichor. The fingers were moved into their new position, and the hand was pickled for two weeks in an earthenware jar with salt, long peppers and saltpetre (potassium nitrate). Then it would either be left to dry in the sun or dried in an oven with vervain, a herb that was said to repel demons.

Finally — in the case of the Whitby Museum Hand of Glory — it was coated in wax. This hand was designed so that the fingers and thumb were lit like gristly candles. So long as they remained alight, all who slept within the household would remain in a deep, unstirred slumber while the burglars went about their business.

If the fingers refused to light, it was an omen that someone in the household was still awake, or that the thieves had miscalculated the number of people in the home. Once lit, the Hand of Glory could only be prematurely extinguished with blood or milk.

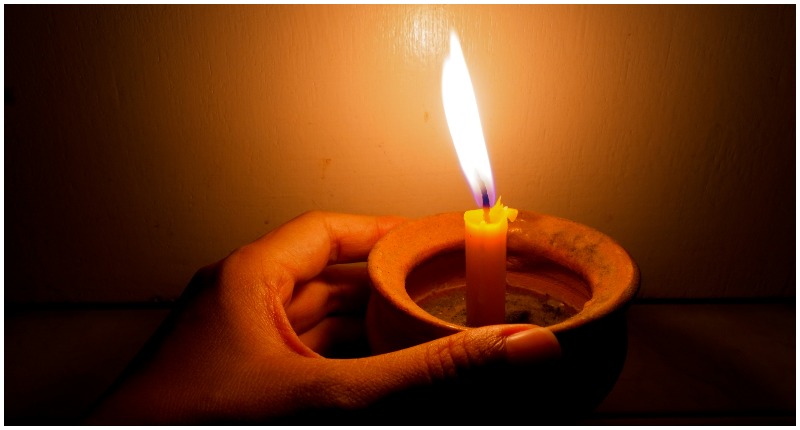

An alternate recipe from the 1722 French grimoire Petit Albert call for the fingers of the hand to clutch a single candle, made from human fat from an executed felon and horse dung, which would burn in the dead man’s grasp.

In this incarnation the burglar should “use the Hand of Glory as a candlestick to hold this candle when lighted, and then those in every place into which you go with this baneful instrument shall remain motionless.”

The same book offers a counter-charm with which the paranoid to protect their households, if you prefer your house smelling like the drains of an abattoir to having it robbed:

“The Hand of Glory would become ineffective, and thieves would not be able to utilize it, if you were to rub the threshold or other parts of the house by which they may enter with an unguent composed of the gall of a black cat, the fat of a white hen, and the blood of the screech-owl.”

This account of the Hand of Glory stopping people in their tracks is echoed in reports from witch trials over a century earlier, attesting to a long belief in the charm.

In 1588 two German women, Nichel and Bessers, confessed to digging up two corpses from the churchyard so that they could make Hands of Glory. A few years later in the 1590s North Berwick Witch Trials — Scotland’s largest and most infamous — a schoolmaster called Dr John Fian was tortured into admitting that he had used a Hand of Glory in order to break into a church and conduct blasphemous inversion of a religious ceremony to honour the Devil.

Read another story from us: The ‘Yeti Skull’ which Still has People Scratching their Heads

These last two may be tall tales born out of forced confessions, but it’s clear at least from Whitby Museum’s Hand of Glory that some people believed enough in these ghoulish charms to make them… and perhaps use them.