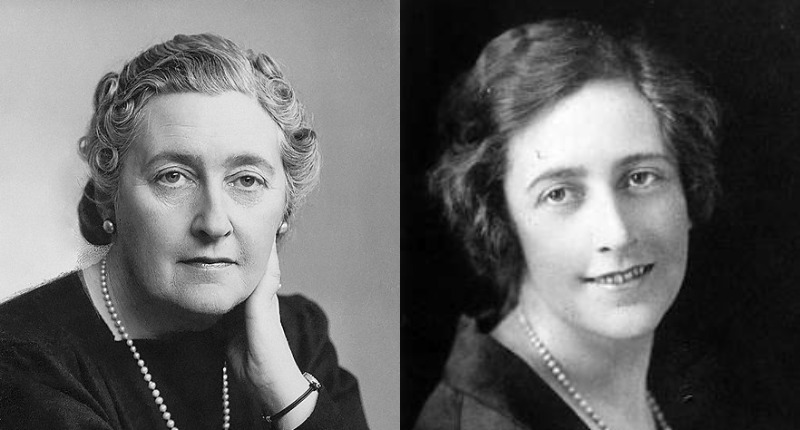

She’s one of the greatest writers of the 20th century — responsible for classic crime chillers like Murder on the Orient Express (1934), The ABC Murders (1935), and And Then There Were None (1939) — but Agatha Christie also took an interest in true crimes, not just inventing fictional ones.

The Detection Club was founded in 1930 by Anthony Berkeley as a society for English crime writers. Christie became one of its 26 founding members, all of them part of the hungry new generation of novelists who emerged in the wake of the first world war.

They captured the gloomy tone of the decades following the war in their writing, which was filled with broken men and women whose decisions don’t fall neatly into a black and white world of right and wrong, and the killer or culprit was often someone the reader least suspected.

They were revolutionaries, whose influence is still felt in books, TV shows, and films, and in every genre from slasher movies to tense thrillers.

Most importantly, Detection Club members were held to the highest standards in their writing, so that it would be shown step-by-step how the likes of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot solved the crime using the evidence presented and their reasoning skills.

Upon joining writers were asked: “Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?”

These were intelligent and insightful men and women, with a keen eye for detail and the inner workings of the most troubled minds.

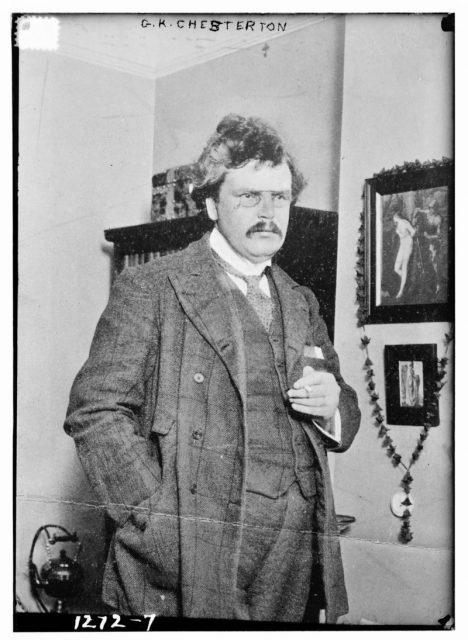

While they were all known for their works of fiction, they shared a macabre passion for true crime too. Agatha Christie, Anthony Berkeley, G.K. Chesterton, Dorothy L. Sayers and the others put their keen minds to the test over their club dinners.

You couldn’t imagine a crowd better suited to finding ingenious solutions to real life mysteries. The 26 founding members of the Detection Club, who included two medical doctors (R. Austin Freeman and Robert Eustace), four veterans of military intelligence (Ronald Knox, Millward Kennedy, Manning Coles, and A.E.W. Mason) and a chemistry professor (J.J. Connington). Christie herself had worked as a nurse in a pharmacy, leading to her knowledge and interest in poisons.

They had referenced true crime in their work before — for example, Agatha Christie referenced the 1932 kidnap of the Lindbergh baby in Murder on the Orient Express — but one case piqued their interest like nothing else.

The Edith Thompson controversy was the hot mystery of its day. In 1923, the 31-year-old was hanged at Holloway Prison in London for the murder of her violent husband Percy.

Edith hadn’t lifted a finger against him, but she had kept up a correspondence with a young seaman she loved, Frederick Bywaters, to whom she bared her tortured soul and shared her unhappiness. One evening as Percy and Edith walked home from the railway station, Bywaters leapt out and fatally stabbed Percy.

The lovers were sentenced to hang. Edith was convicted for “common purpose” because in her letters — an estimated 50,000 words of them — to Bywater she had hinted at Percy’s demise and fantasised about poisoning him.

There was no evidence that Edith was aware of Bywater’s plan — and even he declared her innocent — or that she had sought to poison Percy. Yet on the strength of a few words written in anger, she was sentenced to the noose.

The Detection Club were outraged. The first fiction inspired by the case was Messalina of the Suburbs by E.M. Delafield (1924), followed The Documents in the Case (1930) by Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace.

Agatha Christie referenced the case in Crooked House (1949) and Detection Club founder Anthony Berkley was particular riled by this act of injustice and misogyny, most obviously in As For the Woman (1939).

Although inspired by real events, this was still technically fiction. But in 1936 The Anatomy of Murder crossed over fully into the world of true crime.

It was an anthology of seven stories by seven of the Detection Club, retelling true crime cases from the 19th century to the 1930s. They not only examined the evidence, but explored the motives and psychology of the perpetrators, and even included new details. Anthony Berkeley, of course, wrote about Edith Thompson.

Agatha Christie didn’t contribute to The Anatomy of Murder, but she was accused of inspiring a real murder and helping to expose an attempted murder.

Christie, who became the Detection Club president in 1957 and remained in the post until her death in 1976, was accused by a The Daily Mail newspaper of directly giving English serial killer Graham Young his murderous ideas.

Never mind that Young, aka the Teacup Poisoner, had studied poisons and chemistry from an early age, the gutter press claimed he had gotten the idea from Christie’s 1961 novel The Pale Horse, and that the author had inspired him to murder three and poison seven others.

If Christie was distressed by that, she got some solace from a letter that arrived in 1975 shortly before her death. Written by a woman in Latin America, she claimed that she had been able to spot the effects of thallium poisoning from Christie’s descriptions in The Pale Horse, and acting on her suspicions it was later discovered that the friend’s husband was trying to murder her.

Agatha Christie may have been less keen on directly investigating true crime than her Detection Club colleagues, but in the end true crime came to her.