Spartacus; gladiator, slave, and scourge of the Roman Republic, is a well-known figure in popular culture. The epic 1960 biopic romanticized Spartacus’ slave uprising of 73 BC, and immortalized his name with the iconic line, “I am Spartacus.”

This simple statement has become a mantra for social movements, expressing solidarity and resistance against authority and oppression.

However, the reality of Spartacus’ slave revolt is less straightforward than the stories shaped by popular myth. Spartacus was not the only leader of the uprising in 73 BC, and indeed, his relationship with his fellow commanders may explain the ultimate failure of his fight against Roman rule.

While it is Spartacus’ name that has gone down in history, his co-commander Crixus arguably played just as significant a role in the revolt, and his relationship with Spartacus was an important factor in shaping the outcome.

According to historian Keith Bradley, little is known of Spartacus and Crixus outside the context of the Third Servile War, the name by which the revolt is now known.

It is believed that Spartacus was a mercenary from Thrace who deserted the Roman army and ended up in a gladiator training camp in Capua. It was here that he encountered Crixus, a slave thought to have hailed from Gaul as his name is of Celtic origin, meaning curly-haired.

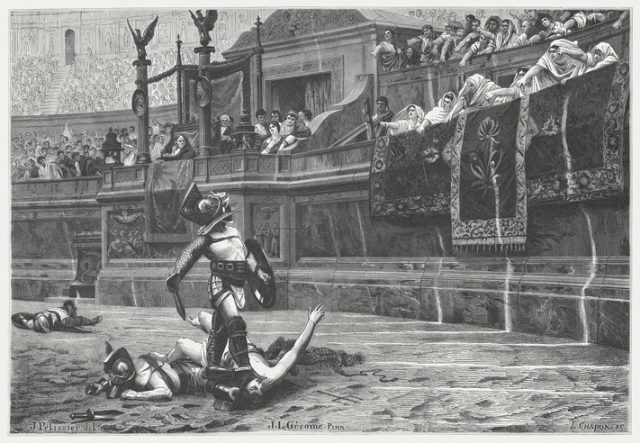

Life as a gladiator was hard, and usually short. Conditions in the training camp were squalid, and by 73 BC, the enslaved fighters were desperate to escape.

One night, following a foiled escape attempt, Spartacus, Crixus and around 80 gladiators seized weapons from the training camp and fought their way to freedom.

The group immediately elected Spartacus, Crixus and another gladiator named Oenomaus as leaders. Escaped slaves would meet with little mercy from Roman authorities.

According to Bradley, earlier slave revolts had been brutally put down by the Roman army, and so Spartacus and Crixus knew that they would need to fight their way out of Roman territory.

They began to plunder the local countryside, encouraging other slaves to rise up and join the revolt. The size of the army ballooned, numbering over 70,000 former slaves, according to the Roman historian Appian.

The Roman response to this crisis was sluggish. Fundamentally underestimating the slave army, the Senate sent successive inferior fighting forces to put down the revolt, to no avail.

With each defeat, the stakes were raised for the Roman authorities, who could not afford to lose face, and who feared a mass slave uprising in other parts of the Republic.

There is considerable dispute over the aims of Spartacus and Crixus. The Roman historian Appian suggests that the leaders of the army intended to march on Rome.

However, there is little other evidence to support this, and it may have simply reflected Roman fears about the trajectory of the revolt. Other historians have suggested that the aim was to lead the slave army to freedom away from Roman rule into Gaul, and there is no evidence to indicate that Spartacus wished to change the social order or put an end to slavery.

What we do know is that at some point in 72 BC, following several important victories against the Roman army, Crixus and Spartacus decided to divide their fighting force.

Some historians believe that this was due to conflict between Crixus and Spartacus, with the former wishing to march on Rome, while Spartacus wanted to go north. However, it may have been a strategic decision, with the two armies planning to meet again at a later date.

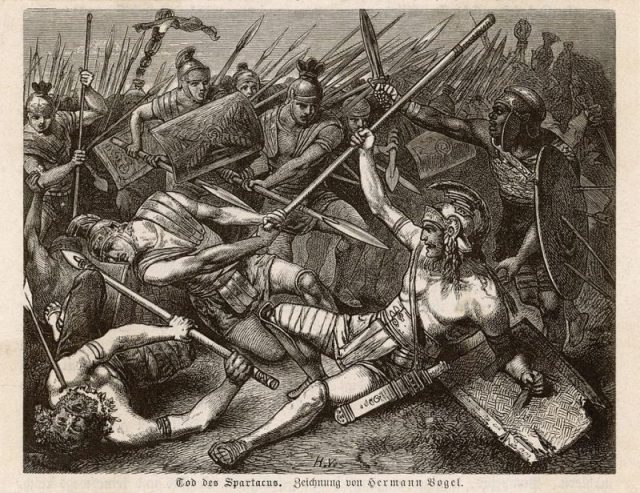

Either way, this choice proved to be fatal. Crixus and his group of 30,000 men were attacked by the army of Lucius Gellius Publicola near Mount Gargano in southeast Italy. The victory of the Romans was decisive, and Crixus died fighting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uuNhLnqbLBw

Spartacus was grief-stricken, and insisted on staging funeral games in honor of Crixus. Captured Roman soldiers were dressed as gladiators and forced to fight, inverting the social order and mirroring Spartacus’ own history.

Read another story from us: Sparta vs. Athens: The War that Lasted 2,500 Years

Sadly, this was one of the last moments of glory for the slave army. Spartacus and the majority of the freed slaves died fighting the Roman army of Marcus Licinius Crassus in 71 BC, and those that survived were crucified. Yet, had Spartacus and Crixus not decided to split their troops, this epic story might have had a very different ending.