As long as people have lived in groups, there have been disagreements between them. The more people in a group, the more potential for disagreements.

Even among prehistoric man there must have been certain agreements between the members of families or clans about how members should, and should not, behave to promote the good of the whole community.

Those earliest rules probably had a lot to do with concerns like sharing resources and mutual protection, tending to the very old and very young, and not running around pointlessly hurting or damaging each other.

As the size of communities slowly grew and became less closely related to and less interdependent, the potential for conflict of all kinds grew, too. As a result, societies needed to start thinking in a more organized and systematic way about what was acceptable within the society and what wasn’t. In short, humans had to start thinking about issues of morality and issues of law.

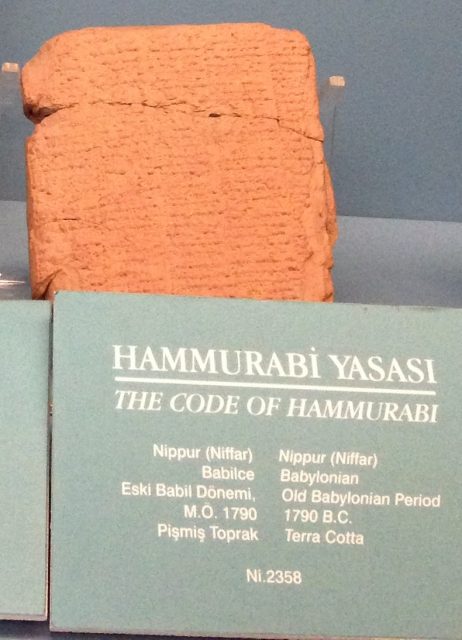

The Code of Hammurabi is one of the first known formal, written codes of law. Hammurabi ruled the Babylonian Empire from 1792-1750 BC. According to U.S.A. History, when Hammurabi first came to power, he only ruled the city-state of Babylon, which was about 50 square miles. Over the course of his rule he conquered other city-states and began building an empire that covered a lot more ground and a lot more people.

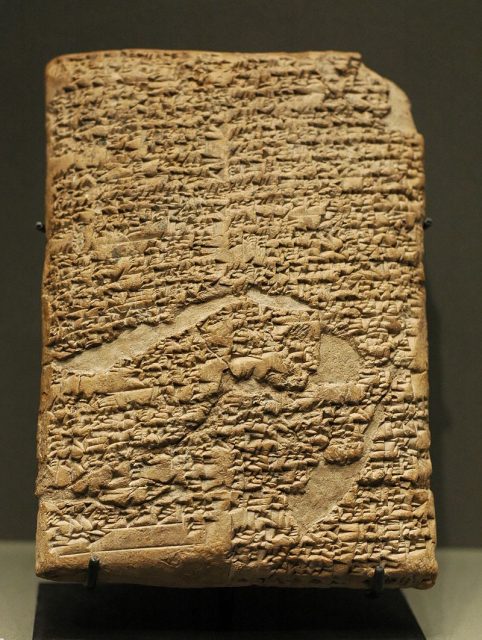

In addition to his general desire to be a just ruler, he also needed a way to keep order in his domain and have a universal set of laws for the entire empire. He began assembling legal experts to gather up all the laws that were already in place in the places he conquered. They were looked over, modified, or sometimes disposed of before he put them together in what became his Code.

Hammurabi’s Code isn’t the absolute oldest written set of laws known to us today. The oldest set of laws we have evidence of is about 600 years older than Hammurabi’s. It’s on a set of tablets that were found in what was the city of Ebla, or modern-day Tell-Mardikh, in Syria.

Even so, Hammurabi’s Code was remarkable for several reasons. One is that he had a sort of prologue to the code in which he outlined his desire to “make justice visible in the land, to destroy the wicked person and the evil-doer, that the strong might not injure the weak.” It wasn’t just talk, either.

There are laws in the Code that are aimed at protecting orphans, widows, and other vulnerable people from not just outright harm, but also from exploitation.

Another of the things that’s noteworthy about the Code is that it is the first known record putting forth the principle of “an eye for eye” which we later see in the Bible. Even there, though, the Code shows complexity and sophistication.

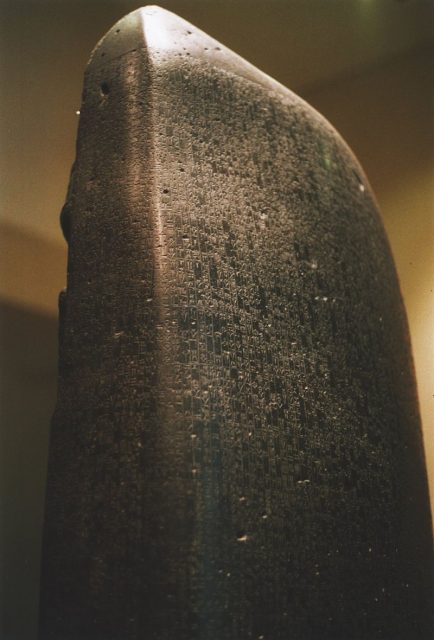

The punishments that are outlined for various crimes are slightly different, depending on where the criminal comes from in society. The noble and rich are given one set of penalties, the lower classes of freemen another, and a different set for slaves. According to History.com, the Code was carved into a ten-foot tall, black, finger-shaped stone called a stele, which was a four-ton slab of diorite.

At the top of the stele is a huge relief showing Hammurabi standing and receiving the law from the seated figure of Shamash, who was the Babylonian god of justice.

The bottom seven and a half feet of the stele is covered with row upon row of chiseled cuneiform writing containing the actual code. The Code itself is less a statement of principle than a statement of precedent, outlining the penalties and retributions for specific crimes.

All 282 of the edicts are structured in an if-then form. One example is “If a son strike his father, his hands shall be hewn off.” Another is “If a man strike a free-born woman so that she lose her unborn child, he shall pay her ten shekels for her loss.”

The stele was taken centuries ago, but was rediscovered in 1901 by a French mining engineer named Jacques de Morgan. He was leading an archaeological expedition to dig in the Elamite capital, Susa, which was about 250 miles from the center of Hammurabi’s empire.

While they were there they found the stele, broken into three pieces, where it had been brought as the spoils of war, probably by King Shutruk-Nahhunte in the mid-12th century BC.

After its discovery it was sent to the Louvre in Paris, where it was translated and widely advertised as the earliest example of a legal code, one that was similar to, but significantly predated, the laws from the Hebrew Old Testament.

Since its discovery there have been other legal codes discovered in Mesopotamia which are hundreds of years older, but Hammurabi’s Code remains a seminal work of law and social justice.