The practice of fudaraku tokai (meaning “the crossing of the sea to Fudaraku”) had all the trappings of a funeral: an elderly monk, usually sealed up in his ship like a coffin — the walls and roof hammered shut with nails — atop a small single-sailed boat with no rudder and oars to steer with.

Watching him go, his friends and family wept as he disappeared over the horizon. The monk was alive and he was a volunteer, but he hadn’t chosen to die — he had chosen to be reborn.

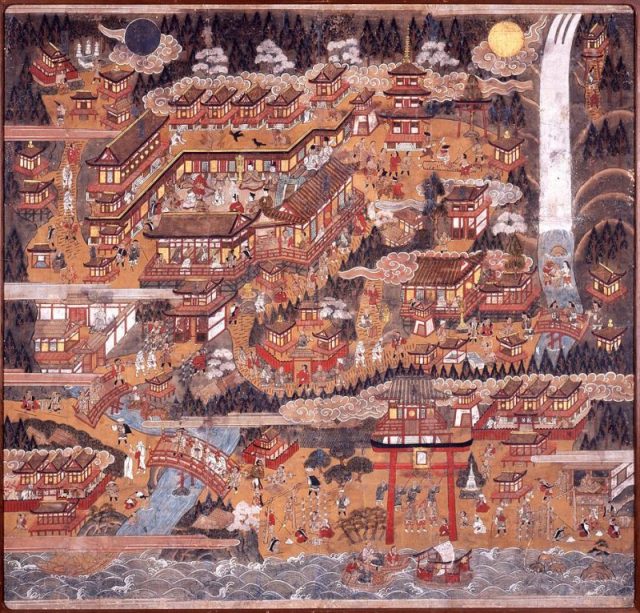

Between the 10th and 16th centuries, aged monks sailed out in small single-sailed boats in the hope of arriving at the island of Fudaraku, the southern paradise of Kannon (known as Avalokitesvara in Sanskrit), the bodhisattva of compassion. In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is someone who has attained enlightenment but has delayed his or her entry to nirvana in order to share their teachings with others.

Those who undertook the journey were usually close to the end. Upon reaching Kannon’s realm, which is called Potalaka in Sanskrit, the monk would be reborn into this new world as an immortal.

They spent their journey in prayer, and perhaps in terror as the reality of their situation hit them, with only 30-days of food and a single lantern to bring them comfort.

Once the food ran out, they pulled a plug in the hull and as the fatal torrent of water poured in, the monk and his vessel sunk beneath the waves towards the afterlife.

Although rooted in Buddhism, fudaraku tokai is a product of the collision of cultures and religions in the region, weaving elements of Taoism and native Japanese folklore to create a tradition unique to Japan.

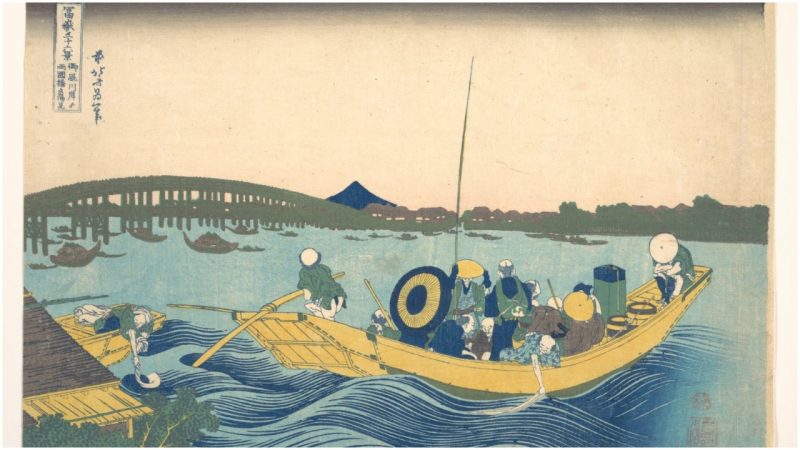

As a nation of islands on the edge of East Asia, it’s inevitable for Japanese Buddhists that the journey to another world is a journey across the water — as opposed to a journey upwards into the heavens, or downwards beneath the earth as is common in the rest of Buddhism.

Fudaraku tokai was closely linked to Fudarakusan Temple, or Fudarakusan-ji, at the town of Nachi (now part of the larger urban area of Nachikatsuura) on the southeastern coast of Honshū, Japan’s largest island.

It was the heartland of the Kannon cult and of the 36 recorded acts of fudaraku tokai, 26 of them took place at Nachi. It was customary for the temple’s abbot to undertake the voyage when he reached the age of 61.

A 12th century diary written by the nobleman Fujiwara no Yorinaga details a conversation with an eyewitness to the act of fudaraku tokai, who reveals the level of prayer and preparation involved in this voyage to the southern paradise:

“There was a lone monk who wished to travel to Mount Fudaraku in his present body. He carved a statue of the Thousand-Armed Kannon, held the helm of a small boat, and for three years prayed that he might be able to travel to Mount Fudaraku. Having completed this, for seven days he performed practices designed to bring about wind and the great northern winds blew. With pleasure, he boarded his boat and faced south.”

The monks took with them offerings from the local community, and in doing so cleansed their souls and guaranteed their health and happiness. Donations funded the constructions of the boats and the carvings of elaborate shrines to decorate them. A common inscription explained their motives: “Peace in this world, birth in a good realm in the afterlife.”

There was a dark side to all of this, though. There’s an account of Konkōbō, the 16th century abbot of Fudarakusan Temple, who had a sinking feeling about his chances of finding this mythical island paradise.

As he was supposed to volunteer for it, the temple were initially unsure how to proceed when the abbot refused to submit to fudaraku tokai. Eventually, to restore the status quo and solve the problem, his assistants cut out the middleman and drowned their elderly leader.

From the 15th century onwards, Japan was increasing visited by European merchants and explorers, and from the 16th century Jesuit missionaries began to cross the island to try and spread the gospel of Christ.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4c9rEL4Nr2s

While their success at converting Japan’s people from Buddhism and Shintoism to Christianity was limited, they did change the religious landscape in in one significant way.

Read another story from us: The Hidden Underground Bodies of the Easter Island Head Statues

With the arrival of these outsiders from distant lands, the idea of Japan as the absolute edge of the world with a mysterious island otherworld lurking somewhere to the south became increasingly hard to swallow. By the end of the 17th century, fudaraku tokai had died out.