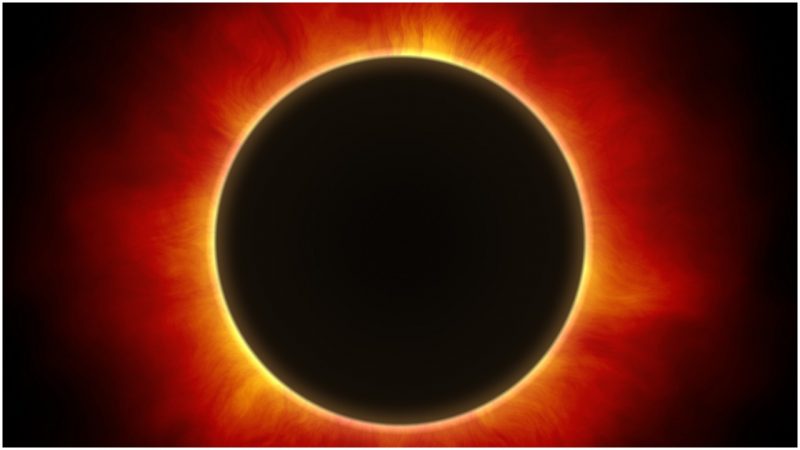

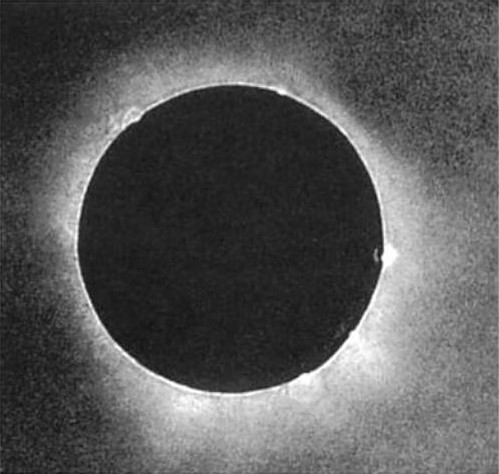

In the late afternoon of May 28, 585 BC, a solar eclipse occurred in the Near East, right at the moment when two rival states were engaged in battle. Interpreting this heavenly disturbance as a sign, the two sides put down their weapons and stopped fighting immediately. This was the eclipse that stopped a war.

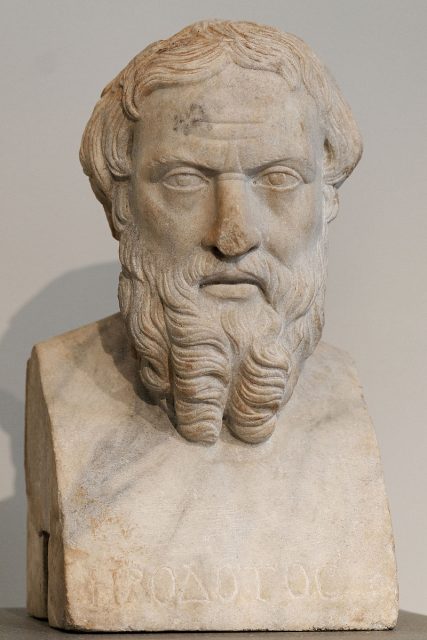

At least, this is the story reported by the Greek historian Herodotus. However, modern historians have puzzled over the event for decades. Astronomical and scientific data have been compared with ancient accounts to determine the veracity of the account.

References to calculable astronomical events can provide vital clues to historians seeking to uncover details about Iron Age societies that have left little trace in written or epigraphic sources.

However, the story of the so-called Battle of the Eclipse is not so straightforward as Herodotus’ account might suggest. According to Herodotus, in the early 6th century BC, two rival states were in conflict over land in Anatolia, in present-day Turkey.

The Lydians were an important kingdom that ruled over Western Anatolia, but their expansionist aims drew them eastwards, into the territory of the Medes, who held an empire covering most of Western Iran. Both states wished to expand their territory, and they clashed in central Anatolia.

By 585 BC, the dispute had been raging for five long years, with neither side making substantial gains. This protracted stalemate was injurious to both sides. The loss of men and resources was taking its toll. Nevertheless, at the end of May, the two armies met once again for a final cataclysmic battle to determine the victor.

Herodotus reports that, as the battle warmed up, “day was all of a sudden changed into night.” As they observed the eclipse, the fighters put down their weapons. The two armies began to negotiate, eager to have the conflict resolved as quickly as possible.

Inexplicable occurrences in the sky were often interpreted as signs from the gods, and both the Lydians and Medes understood the eclipse as a sign of the gods’ displeasure at their incessant fighting.

Indeed, a full solar eclipse would have had a significant effect on any observers. Eclipses are often accompanied by changes in wind speed and direction, and the growing dark can confuse birds, disturbing their circadian rhythms and causing them to circle, frantically searching for a place to roost.

Add to this the darkening of the sky, and it’s easy to see why the Lydians and Medes would have thought the eclipse to be a threatening omen.

According to Herodotus, the two sides quickly came to terms, agreeing the boundary between the two kingdoms would be the river Halys (thought to be the modern-day river Kizilirmak).

Astyages, the son of the Median ruler Cyaxares, and Aryenis, the daughter of the Lydian king Alyattes, were betrothed in order to secure the agreement and guard against any further hostilities. The eclipse had brought a peaceful end to the six-year conflict.

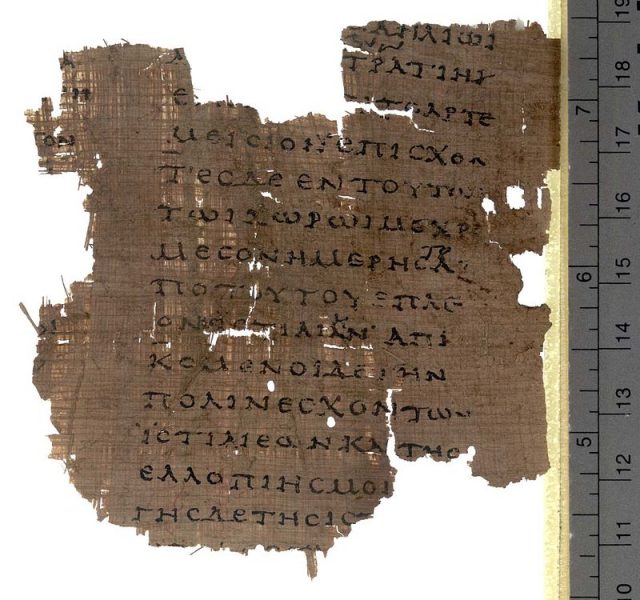

However, modern historians have discovered many inconsistencies in Herodotus’ account. Astronomical data places the eclipse at May 28, 585 BC, but other ancient sources such as Eusebius, Solinus and the Oxyrhynchus Papyrus report that Cyaxares had died by this point, and the decisive battle took place under the rule of his successor Astyages.

There is no other archaeological or historical record of the battle, and some historians believe that the cessation of hostilities between the two sides took place a long time after the supposed date of the Battle of the Eclipse.

Historian Kevin Leloux suggests that the two events actually took place years apart, but that they were conflated in the minds of Greek commentators such as Herodotus, who was not an eyewitness to the events. He was born 100 years later, in 485 BC.

Whether his report is right or wrong, however, his framing of the battle and the eclipse reveals important details about the perspectives of 5th century Greeks on the historic war between the Lydians and Medes.

Although we may never know the truth about the legendary Battle of the Eclipse, Herodotus’ storytelling has resonated over thousands of years.

Read another story from us: New Evidence Proves that Humans did Indeed Hunt Mammoths

It certainly would be nice to think that such astronomical events could bring about the end of major conflicts, however entrenched they might be.