Victorian children had dolls to play with just like children do today, and — kids being kids — these dolls were cuddled like infants, taken on outings, and joined in tea parties, games or whatever world of make-believe their owners conjured up.

Accessories for dolls were varied as they are now, but one was typically Victorian: It was a tiny black mourning dress and a tiny coffin. Children would play at laying out the doll as they might one day do for their own loved ones.

Even without the long black funeral gown, a doll was likely to receive last rites. The English author Mary Carbery, who was born in 1849, recalled her siblings and cousins burying her favourite doll, Otto, in the garden during a “game of funeral.”

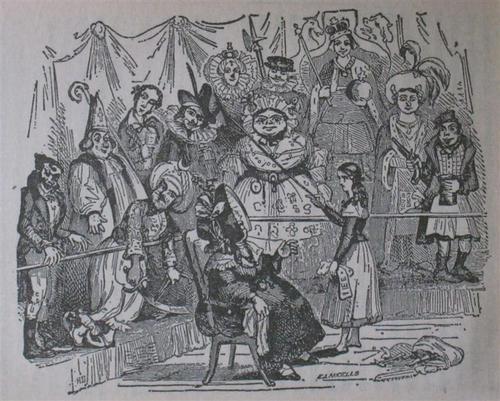

“Playing funeral” was common across the mid- to late-1800s. In Charles Dickens’s 1840 novel The Old Curiosity Shop, his protagonist, Nell, stumbles across a group of children in a graveyard “playing funeral” with a very realistic doll — their baby brother or sister.

“Some young children sported among the tombs, and hid from each other, with laughing faces. They had an infant with them, and had laid it down asleep upon a child’s grave, in a little bed of leaves.”

The possibility of a premature end hung heavily over children’s rhymes, singing games and bedtime stories like a shroud.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) is crammed full of poisons and the threat of fatality, Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies (1863) begins with its hero drowning, and JM Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904) was inspired by the demise of the author’s brother, David, who died aged 14-years-old after a skating accident.

The English writer and poet Christina Rossetti published Sing-Song: A Nursery Rhyme Book in 1893, and if you’re wondering why you never heard these at pre-school, it’s because the subject matter can get a little macabre:

“A baby’s cradle with no baby in it,

A baby’s grave where autumn leaves drop sere;

The sweet soul gathered home to Paradise,

The body waiting here.”

And another:

“Baby lies so fast asleep

That we cannot wake her:

Will the angels clad in white

Fly from heaven to take her?”

Religion played a role of course. Children’s prayers, psalms and hymns all kept the possibility of death — and the Christian faith needed to embrace it — firmly at the forefront of their minds.

A particularly heavy handed example was the hymn ‘One day, dear children, you must die’, which appeared in the book Hymns for Infant Children (1862):

“One day, dear children you must die

Though you are young and healthy now

Within the grave your limbs must lie

And cold and stuff your bodies grow”

The industrialization of the mid-19th century had led to the rapid growth of towns and cities as country folk moved for work, forcing them to live together in areas of high pollution and poor sanitation.

These were perfect environments for all manner of illnesses to thrive, such as smallpox, measles, whooping cough, diphtheria, tuberculosis and dysentery, followed by periodic epidemics of cholera, scarlet fever, typhoid or influenza.

These are all preventable or treatable today, but for the bulk of the 1800s medicine simply wasn’t up to the task, and children were especially vulnerable.

The infant mortality rate in England and Wales in the 1890s was approximately 15 percent — 150 out of every 1,000 children were expected to pass away before adulthood.

In some urban neighborhoods it was much higher — around 30 percent in the Borough of Islington in North London, suggesting that the comparative health of rural or middle class youth versus their slum-dwelling city counterparts was pulling the average down.

As an all-too-real fact of their young lives, Victorian parents had to prepare their children because the odds were they would likely soon lose a brother or sister, school friend, or even themselves.

Read another story from us: Mary Really did Have a Little Lamb – The True Story of the Nursery Rhyme

Grief was real and the pain of losing a loved one was felt as keenly then as today, but in letting their offspring explore mortality through their toys, games and stories, Victorian mothers and fathers were doing the best they could to ensure their children lived without fear.