The history of imperialism and empire-building has left a dark legacy on the world that many are still coming to terms with. While certain dictators and their ambitions — most notably Hitler — are well-known, other figures fade into the background.

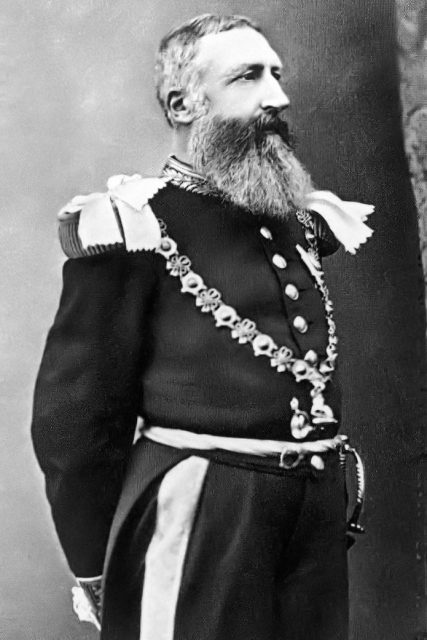

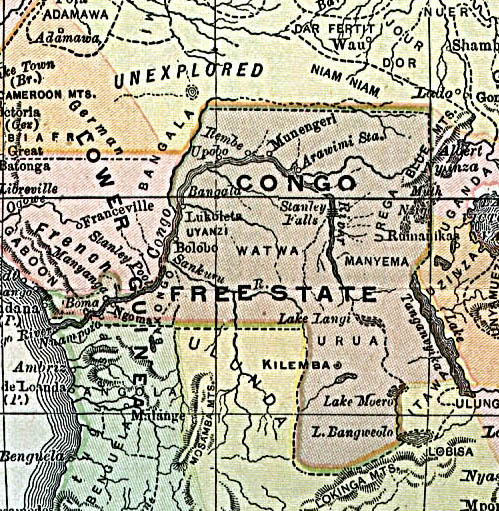

One of those figures arguably is Leopold II of Belgium, who between 1885 and 1908 created the notorious Congo Free State in Central Africa.

As described in a Guardian piece from 1999, “Leopold certainly emerges as an unattractive figure, described… by (Benjamin) Disraeli as having ‘such a nose as a young prince has in a fairy tale, who has been banned by a malignant fairy.’”

Some regard him as a callous invader who would stop at nothing to realize his business interests. Others believe him to be a more misunderstood individual. Reckless yes, but blind to some of the atrocities carried out in his name.

Why did Leopold take control of this area in the first place? The New Yorker wrote in 2015 that he claimed to want civilization for this faraway continent.

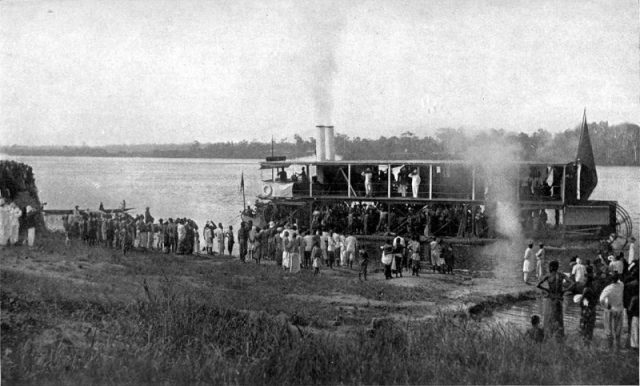

He “wanted his country to join the league of European empires, but the Belgian state refused to finance its part in western Europe’s expensive scramble for Africa. So they outsourced the task to Leopold, who used personal diplomacy to convince the European powers to grant him control of a large portion of the Congo basin.”

The forces of commerce and the power of money soon turned this journey into something much darker. Dense jungle was seen as a valuable source of rubber. The Congolese were forced to risk life and limb, slashing vines and exposing themselves to the raw material, which welded itself to their skin.

“Leopold’s playground was an astonishing 76 times the size of Belgium,” The New Yorker observed. “The Congo Free State evolved from a vanity possession into a slave plantation.”

This relentless quest for profit had many agents, who would violently push the population toward their goals. The Guardian says, “many of Leopold’s officials… terrorised the local inhabitants, forcing them to work under the threat of having their hands and feet — or those of their children — cut off. Women were raped, men were executed and villages were burned in pursuit of profit for the king.”

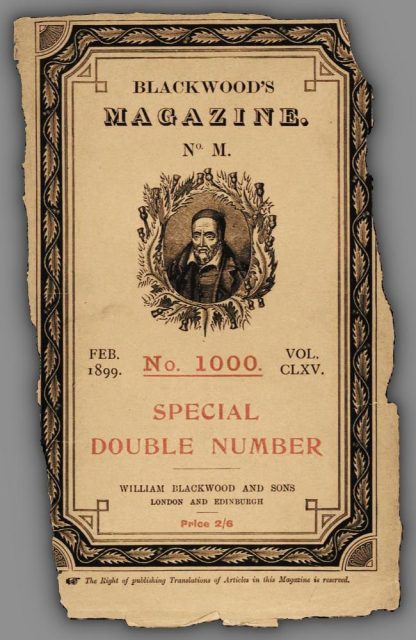

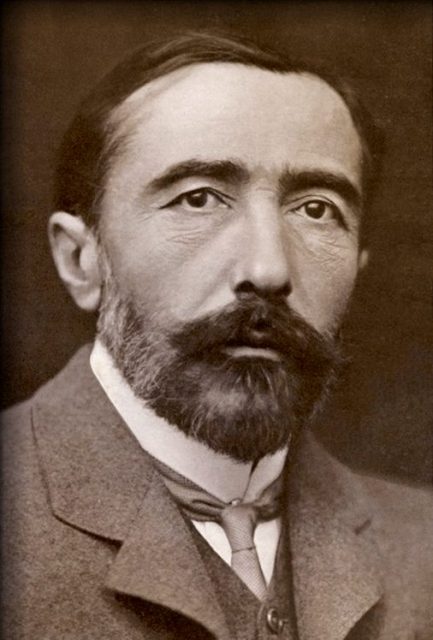

A particularly grisly detail was a trade in severed hands, which were delivered in lieu of a missed quota. The nightmare of that time and its bleak psychology was immortalized by Joseph Conrad in his 1899 novella Heart of Darkness, the basis for war movie odyssey Apocalypse Now (1979).

“With its grisly, bloody imagery, one might imagine that Conrad exaggerated the awfulness of the regime,” the New Yorker wrote. “In fact the cold details of missionary journals make even more horrifying reading.”

Eventually the wider world became aware of what was going on in the Congo Free State. The outcry led to it being taken out of Leopold’s control in the early 20th century.

The bloodshed didn’t quite end there. History Today noted in 2012 that “Even after the Congo Free State was abolished and an official Belgian colony was established, in 1906, the atrocities continued, including the death of more than seven thousand forced laborers who were pressed into expanding a railroad in the nineteen-twenties.”

It was a real life horror on an epic scale, with millions said to have perished. However some historians and other commentators have stopped short of calling Leopold’s ruthless reign a “holocaust.”

The Guardian quotes Barbara Emerson, who wrote a book on Leopold. She argues “Leopold did not start genocide. He was greedy for money and chose not to interest himself when things got out of control. Part of Belgian society is still very defensive. People with Congo connections say we were not so awful as that, we reformed the Congo and had a decent administration there.”

Nevertheless, the things carried out on his watch stained his reputation forever. The New Yorker states, “Estimates for the number of people killed range between two and 15 million, easily putting Leopold in the top ten of history’s mass murderers. When he died in 1909 the king’s funeral cortege was booed.”

Comparisons are inevitably drawn between what happened then and more famous outrages. Leopold’s time connects “the imperialism of the 19th century and the totalitarianism of the 20th… the sheer scale of the terror, the role of bureaucracy and the near-genocidal numbers of dead draw comparisons with Hitler’s Lebensraum and Stalin’s war on the Kulaks.”

Whether Leopold can be viewed as a dictator or a cold-hearted businessman, the chaos he instigated has echoed through the ages. The truth behind his rule is certainly uncomfortable for some, yet the industrial levels of human misery cannot help but be acknowledged.

History Today sounded a note of caution when summing up the role of Leopold in the Congo. While evil was present in the jungles of his Free State, the conquest and exploitation was by no means unique to Belgium.

Read another story from us: The Madness of King George and the Unsightly Blue Stuff it Produced

“While it’s clear that much of the Belgian public is still ambivalent about the country’s history in Africa,” it says, “it should be noted that the citizens of many other former colonial powers also have complicated relationships with their own histories.”

The scars of so-called civilization are visible hundreds of years on, and will likely never fade.