Thomas Edward Lawrence, otherwise known as Lawrence of Arabia, is an icon of British history. This Oxford-educated scholar and spy played a crucial role in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, an event that would determine the future of the region and pave the way for the conflicts of the 20th century.

Yet, according to biographer Scott Anderson, Lawrence’s legacy is still highly contested. For some, he is the romantic vision of a benign British orientalist, a friend to the Arabs and an unfortunate victim of political decisions that were beyond his control.

For others, however, he was a complicit agent in the imposition of British imperialist rule in the Middle East, who fundamentally betrayed the Arab cause that he had once so passionately espoused.

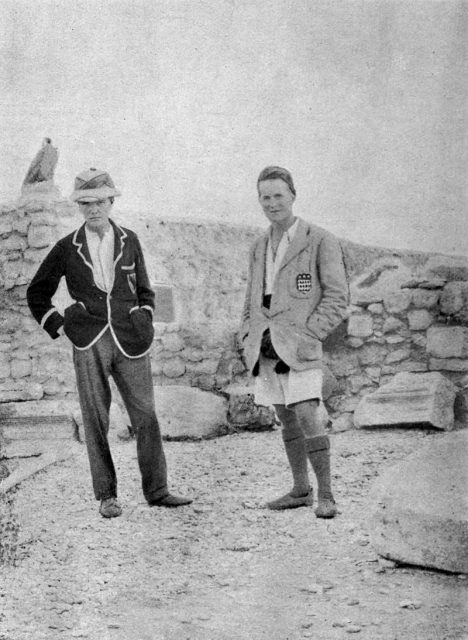

Lawrence was educated in History at Oxford and spent his early years after graduation assisting on archaeological digs in Syria. During this time he learned to speak Arabic, and developed a keen passion for Arab culture, history and politics. His time in Syria led him to support the burgeoning Arab independence movement within the Turkish-led Ottoman Empire.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Lawrence was sent to Egypt, in order to put his language skills to use in the intelligence bureau. However, according to Anderson, after two years behind a desk, he was anxious to return to the field.

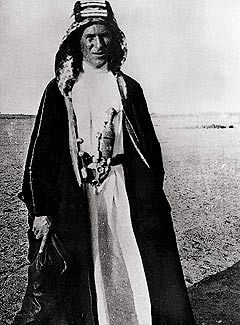

The Arab nationalist movement was agitating against Ottoman rule, and the British realized that this might offer the perfect opportunity to destabilize the Empire and further the Allied cause. In the Arabian Peninsula, the Hashemite king of the Hejaz, Hussein, had already made substantial gains against the Ottomans by taking control of the cities of Mecca and Jeddah. Lawrence was sent to the Hejaz to learn what he could about the prospects of Arab Revolt and to urge the Hashemites to lead a larger offensive against the Ottoman Turks.

According to Anderson, Lawrence attached himself to Faisal, one of Hussein’s sons. Faisal was an intelligent, charismatic leader and Lawrence believed that he could be the ideal person to unite the Arab tribes and coordinate a full-scale uprising against the Ottomans. In return, he promised British support, crucially, in the establishment of an independent Arab state in the case of Ottoman collapse.

Lawrence and Faisal successfully united the Arabs and made a series of extraordinary victories against the Ottomans, most notably, taking the port of Aqaba after a grueling two-month journey through the desert.

However, as he was swept further up into the Arab Revolt, Lawrence felt an increasing sense of unease and guilt. He knew that the dream of an Arab state was futile, because the British authorities had double-crossed the Hashemites. While dangling the prospect of Arab independence to encourage an Arab Revolt against the Ottomans, the British had made a secret pact with the French.

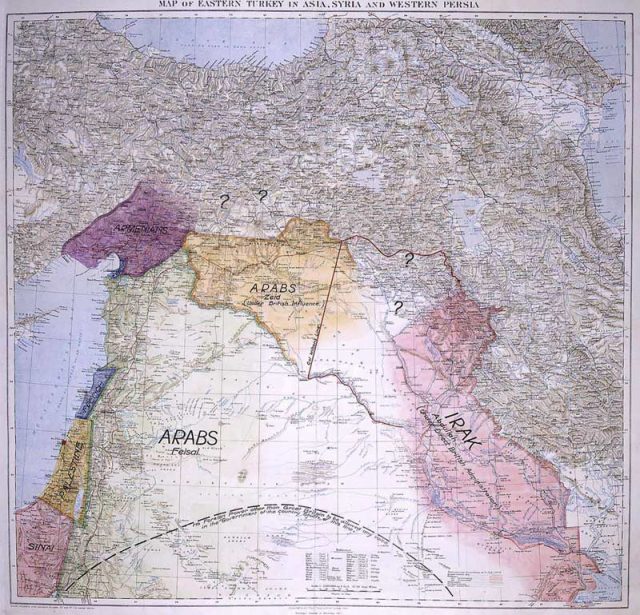

Under the terms of this pact, known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, there would be no independent Arab state once the Ottoman Empire finally disintegrated. Instead, the region would be divided into two spheres of influence, with Syria and Lebanon falling under French control, and Iraq, Palestine and the Transjordan falling to the British.

This was a profound betrayal of the Arab cause, and of the promises made by the British to Faisal and his father. According to Anderson, as Lawrence drew closer to Faisal and the Arab cause, he began to feel torn in two, divided between his duty as a British agent and the loyalty he felt he owed to Faisal.

In an act of grave sedition, Lawrence told Faisal about Sykes-Picot. Faisal decided to pre-empt the agreement by rousing the Syrian Arabs and marching through the desert to Damascus. If they could take the city before the French arrived, perhaps it would forestall the implementation of Sykes-Picot.

Although Faisal successfully reached Damascus, the dream of a unified Arab state that spanned the region never materialized. General Allenby arrived in Damascus and dismantled the Arab government that Faisal had installed. Damascus was given over to the French, and the terms of Sykes-Picot were honored. Although Lawrence continued to campaign for the Arab cause, in reality, he knew there was little hope.

Lawrence returned to Britain in 1921 and was stationed in military bases across England. However, he was a broken man, and never fully recovered from his traumatic experience in the Middle East. He became increasingly depressed and withdrawn, and died in a motorcycle accident in 1935, at the age of just 46.

Yet Lawrence’s legacy lives on and continues to divide historians and commentators. The idealistic visionary presented in David Lean’s 1962 biopic Lawrence of Arabia has, in the view of some, obscured the darker side of Lawrence’s actions in the Middle East, and absolved him of responsibility for the part he played in the ultimate failure of the Arab independence movement. However, others suggest that Lawrence himself was merely a pawn, and had no real capacity to shape British policy in the Middle East, despite his sympathies for the Arab cause.

A century on from the end of the First World War, the Arab Revolt, Sykes-Picot, and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire continue to be the source of debate in the contemporary Middle East. In many ways, the region is still dealing with the fallout of these pivotal events, and is still coming to terms with the conflicts and fissures created by the imposition of the British and French Mandates. Although a hundred years have passed, Lawrence’s divisive legacy still looms large over the region.