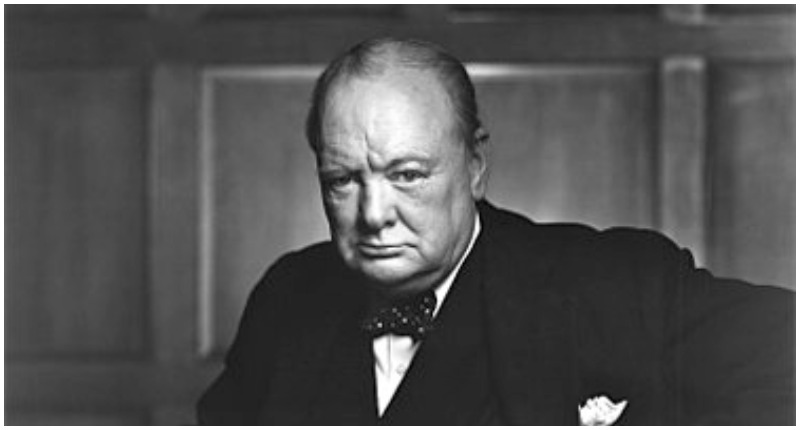

Winston Churchill is, without a doubt, Britain’s most famous Prime Minister. He is the politician who led Britain to victory against Nazi Germany, and is remembered for his impassioned, eloquent speeches and his bold, decisive leadership at a time of national crisis. It’s no wonder that he was voted as the greatest Briton of all time in a BBC poll of 2002.

However, in recent years, historians have begun to reassess Churchill’s legacy, deconstructing the myths that have sprung up around the man since the middle of the 20th century. While it is clear that Churchill performed an incredible service as Britain’s wartime leader, other episodes from his life as a politician tell a somewhat darker story.

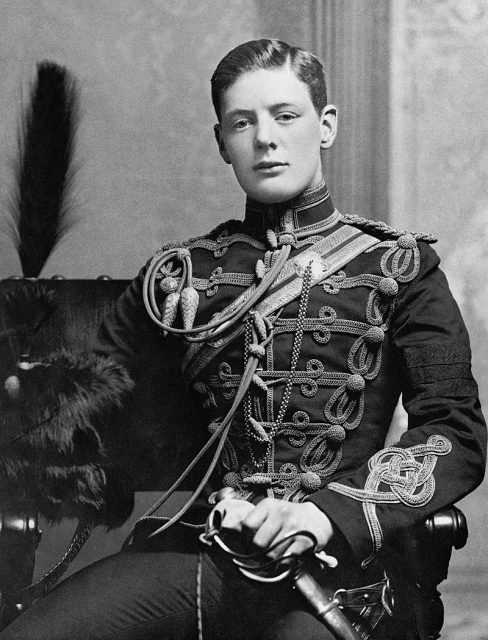

Winston Churchill was born in 1874, to an aristocratic family that had long dominated the British elite. This was a period of British imperial expansion, and the Victorian age was defined by its paternalistic attitude to the subject peoples of colonized territories.

Churchill’s early career saw him sent to various war zones as part of the British Army, including Cuba, India and Sudan. According to historian Richard Toye, this early induction into imperial administration affirmed Churchill’s view that the role of the British Empire was that of a civilizing agent: to bring civilization to the barbarous tribes and peoples of the world.

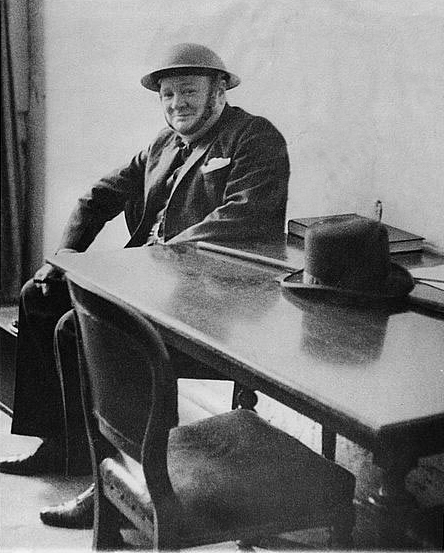

During the Boer war, Churchill was working as a journalist and sent to cover the conflict in South Africa. The Boer war represents a dark stain on the British record in Africa; the British policy of incarcerating indigenous Africans and the families of Boer guerrilla fighters led to the deaths of tens of thousands of innocent men, women and children in disease-riddled concentration camps.

However, on visiting the camps, Churchill remained unmoved by this cesspit of human suffering, suggesting that they were an appropriate strategy in the fight against the Boers.

According to The Independent, as his parliamentary career developed in the early 20th century, Churchill became known for his extreme views on imperial governance. His attitude to the subject peoples of the Empire was strangely paradoxical. On the one hand, he described them as benign children, who needed to be brought under the civilizing wing of British imperial rule.

However, when they rebelled, he looked upon them with an almost inhuman dispassion, approving the use of extreme violence to keep indigenous populations in line.

He advocated the use of poison gas against the Kurds, and imagined violent and gruesome methods by which Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the non-violent Indian independence movement, might meet his end.

Churchill’s dislike of India and the Indian people is well documented. Among other remarks, he is known to have said, “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion”.

When famine broke out in West Bengal in 1943, Churchill refused to send food supplies, despite the fact that the famine itself had been directly caused by British colonial policies. According to The Independent, as the casualty toll rose to a horrific three million, Churchill is said to have remarked that this was an effective way to cull the population.

It is very difficult to square these statements with the Churchill who avidly defended the democratic rights and freedoms of the British in the face of Nazi authoritarianism. His actions during the Second World War and his dramatic speeches, passionately calling for freedom from tyranny, are rightly considered a source of considerable national pride in Britain today.

Yet, it is also important to recognize that for Churchill, these rights and freedoms were not universal. In fact, he seemed to believe that tyranny and authoritarianism should be tolerated when it came from the British, who in his view were legitimate, civilizing conquerors.

Defenders of Churchill have suggested that these views were commonplace in the early 20th century, and that the majority of British parliamentarians would have held comparable views.

However, Toye suggests that this argument does not hold up to scrutiny. Even by the standards of the time, Churchill was considered an extremist by many of his peers; a believer in a brutal imperialist ideology that was fast losing popular support.

Churchill’s image is so intimately tied up with British national identity and the idea of anti-authoritarian struggle that it is particularly difficult to reconcile his cruel and punitive ideology with his perceived heroism and eloquence.

However, in recent years historians have built a more nuanced and balanced picture of this complicated man, breaking down the patriotic myths that have glorified his legacy, and providing a more complete picture of his life, politics and legacy. Perhaps it is possible for him to exist as both hero and villain in the British national story.

In the end, Churchill’s rousing wartime rhetoric, espousing the principles of liberty and freedom, had an effect that he himself might not have foreseen (or indeed welcomed).

Read another story from us: Hitler Plotted to Assassinate Churchill with…Exploding Chocolate

The subject peoples of the British Empire, many of whom had bled for Britain during the First and Second World Wars, appropriated his rhetoric of freedom from authoritarianism in their own drive for liberation from the British imperialist yoke.

The world that he created with his wartime speeches and leadership was fundamentally incompatible with the imperial ideology of his youth.