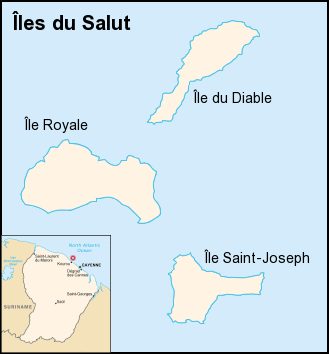

Devil’s Island prison is a place that lives in infamy. About nine miles from Kourou, a small coastal town in French Guiana on the northeastern coast of South America, is a group of three islands called the Îles du Salut, known by English speakers as the Salvation Islands.

The islands are mostly overgrown jungle which is slowly covering the remnants of an infamous French penal colony — where over 60,000 men were incarcerated and less than 2,000 survived. The penal colony of Cayenne, more commonly known as Devil’s Island after the smallest and most notorious of these prison islands, was established in 1852 and operated until 1953.

Devil’s Island itself, the Île du Diable, was first used as a leper colony, and later for the incarceration of political prisoners. Due to treacherous rocks and strong cross-currents around the island, safe access was only possible via a cable car which crossed the 60-foot-wide channel between Île du Diable and the main island, Île Royale. This is where the general prison population was housed and allowed to roam with relative freedom. Solitary confinement was meted out on the southernmost island, Île Saint-Joseph.

Although escape was always on the minds of the prisoners, it was virtually impossible because of the sharks that circled the island — waiting for the bodies of prisoners who died in captivity, that were thrown into the ocean. There is a cemetery on the island, but few inmates are buried there.

Inmates were stuffed into overcrowded cells, most no larger than a typical bathroom in someone’s home. Isolation in a totally dark room with no one to talk to for months at a time was the punishment of choice. Some convicts were put into deep, 12 by 12-foot holes with bars on the top and were subject to all types of weather. Men went mad because of the beatings, both by guards and other prisoners, the solitary confinements, and the lack of food and water.

Convicts were shackled day and night and fell prey to rats, army ants, and vampire bats. Prisoners were forced to harvest wood from underwater and suffered backbreaking toil building a road, named Route Zero, that was never to be used.

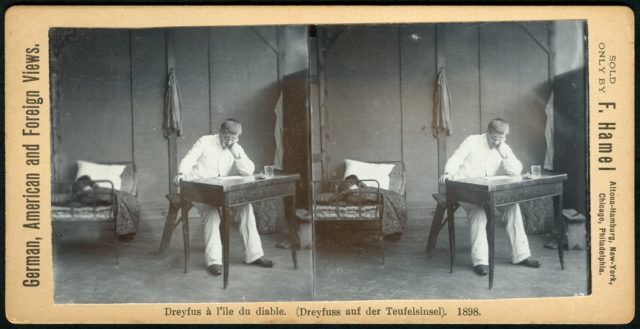

High-profile prisoners incarcerated at Devil’s Island included Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a French military officer who spent almost five years on the island. He was accused of spying for the Germans in 1894 and sentenced to life imprisonment.

The trumped up charges were later found to be nothing more than forgeries, and the entire fiasco of the Dreyfus Affair was mostly got put down to antisemitism, as Dreyfus was Jewish. After several trials that were complete travesties, Dreyfus was acquitted in 1906, according to History.com.

Convict Rene Belbenoit, who spent six years on the island, escaped by helping out a film company. He earned about $100 and used it to bring a Chinese merchant boat to the island. When it left, Belbenoit hid in the boat.

He was dropped off on the mainland and spent months recovering with a native tribe. He made his way on foot through South America, up through Central America and Mexico, and finally into the United States. Belbenoit published his book, Dry Guillotine, in 1938, causing the French to take a long, hard look at what was happening within the penal colony.

French safe cracker, alleged pimp, and petty thief, Henri “Papillon” Charriere is perhaps the most well-known prisoner to have been held on Devil’s Island. He was tried and convicted of murder in 1913, spending 13 years in the notorious prison.

Charriere always maintained his innocence and claimed to have been framed. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, Charriere made two “successful” escapes from the island. The first, in 1916, was in a boat in which he traveled about 1,800 miles to Maracaibo where he was taken in by an Indian tribe.

Not long after he left the tribe, he was recaptured and sent back to prison. He made seven more attempts, and the final — truly successful — escape in 1944 saw him sail away on a raft built of coconuts.

He made his way to Venezuela and stayed there for many years, eventually opening a restaurant. In 1968, he wrote an autobiography, Papillon, which dealt with his time at Devil’s Island.

The book was an instant best-seller and was later made into a movie, starring Dustin Hoffman and Steve McQueen, in 1973. The success of the book was instrumental in allowing Charriere back into France in 1970.

Georges Ménager’s Les Quatre Vérités de Papillon (The Four Truths of Papillon), in 1970, and Gérard de Villiers’ Papillon épinglé (Butterfly Pinned), also 1970, claim that Charriere made up many of the events in his book and stole the experiences of others. A blog post on Barnes & Noble also debunks many of the claims made in Charriere’s book.

Devil’s Island prison no longer houses criminals, having closed down in 1953, and the group of islands has become a tourist attraction. Visitors are not permitted on Devil’s Island and can only explore Royal Island, where a few cells and the administration buildings were kept.