Despite the fact that Antarctica was discovered, or at least spotted, in 1820, the first time man set foot on the continent proper wasn’t until Alexander von Tunzelmann in 1895, according to the New Zealand government’s website, New Zealand History.

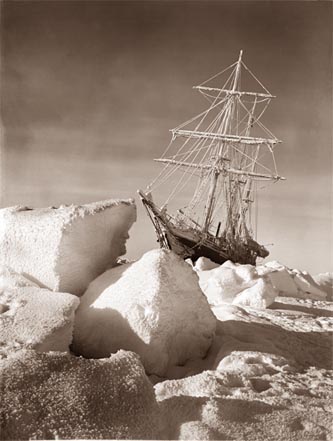

That same year, the Sixth International Geographical Congress met in London and adopted a resolution to the effect that the Antarctic was the greatest piece of geographical exploration that had yet to be taken on, and the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration began. From 1895 until about 1917, when Shackleton’s expedition on the Endurance went awry, there were a number of expeditions to that region, all aimed at exploration and scientific research.

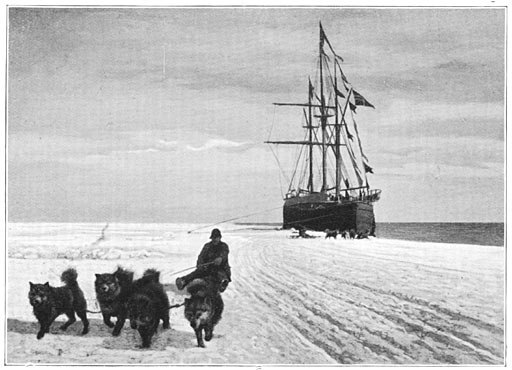

Along with the two-footed explorers and adventurers, there were also travelers of the four-footed variety who provided not only a means of transportation for men heading into the interior but also a source of companionship.

The name “husky” is often used to describe a number of breeds of northern-hemisphere snow dogs. The dogs originated in Labrador and Greenland and have thick, double-layered coats that make them especially well-suited to the sorts of extreme weather conditions found in environments like the Antarctic.

According to Cool Antarctica, the first Huskies to be used in the Antarctic were brought to the continent by the British Antarctic Expedition. Shortly after the expedition arrived at Cape Adare in February 1889, a four-day blizzard blew in and caused seven of the men to be stranded on shore. Those men survived the bitter conditions by erecting a large tent they had with them and bringing all 75 of their dogs into it with them to keep warm. It was a strong and vivid first encounter demonstrating how crucial the canines were to man’s survival on the continent.

In April, one of the team’s dogs got stranded on an ice floe and was blown out to sea. The team thought the dog was a goner, but it returned about two and half months later, and in good condition, showing how well-suited huskies are to the climate.

The dogs were used to pull sleds during treks around the continent; sledges were the only viable method of transportation before mechanical transports.

When motorized vehicle transport became an option, which happened much later in Antarctica than elsewhere in the world, dogs and sledges remained popular, as they were more reliable in the harsh weather. Also, they were better company.

According to the website of the Australian Antarctic Division, the Australians built Mawson Station in 1954 as part of the country’s Antarctic program. When the station was established, they brought in a number of huskies for transport and companionship purposes, and dogs remained a working part of base operations for the next 40 years.

Bases operated by other nations also continued to use sled dogs through the 1960s and into the ‘70s, as the animals were quick, agile, and not put off by the lack of established trails, let alone roads.

Slowly, snowmobiles began to become more common and the use of dog sleds started to diminish, although a number of bases kept some dogs anyway, as a backup to mechanized transport or for the sheer fun of it.

That continued until 1991, when the members of the Antarctic Treaty began implementing the Protocol on Environmental Protection. One of the items the protocol required was the banning of all non-indigenous species except humans. This was due to fears of disease outbreaks occurring which could easily have devastating effects across Antarctica.

The iconic Huskies had to go. The following year, the last half-dozen remaining sled dogs at Mawson station left Antarctica for good. It was an end of an era. The older dogs were retired to Australia, where they could live out the rest of their years in comfort, and the younger animals were taken to Minnesota to be trained as working dogs.

Even though the era of the Antarctic sled dog is long over, the furry explorers haven’t been forgotten. A bronze sculpture of a husky sled dog was erected in front of the British Antarctic Survey headquarters in Cambridge, England in 2009. The funds for the sculpture were raised by three of the men who lived and worked with the dogs in Antarctica.

Read another story from us: Europe’s Most Beautiful Christmas Markets

In Antarctica itself, many of Mawson’s Huskies were remembered when their names were given to 26 landmarks in Antarctica in 2017, including various reefs, rocks, and islands. Those memorials are a lasting legacy to remember the creatures that proved to be such an integral part of the continent’s exploration.