The Statue of Liberty, believe it or not, is not the biggest nor the most impressive architectural contribution France has made to America. For much of Washington DC was in fact designed by a Frenchman.

Born in France in 1754, Pierre Charles L’Enfant grew up following in the footsteps of his famed painter father who was in the service of King Louis XV.

L’Enfant left his studies at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris, however, to go to America and fight on the rebellious colonials’ side in the Revolutionary War.

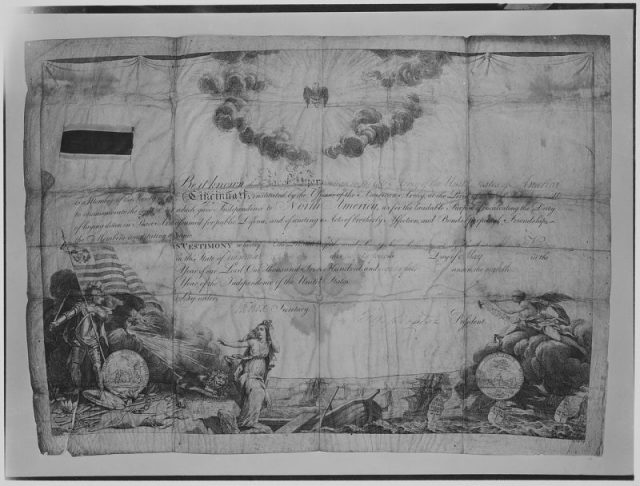

In 1777 he enlisted in the Continental Army under General Lafayette as a military engineer. He went on to serve under General Washington himself, forming a close relationship aided by his production of several portraits of the future first president.

After the war, L’Enfant set up a civil engineering firm in New York. He redesigned City Hall for the First Congress of the United States, providing the first example of the renowned Federal Style architecture for the country.

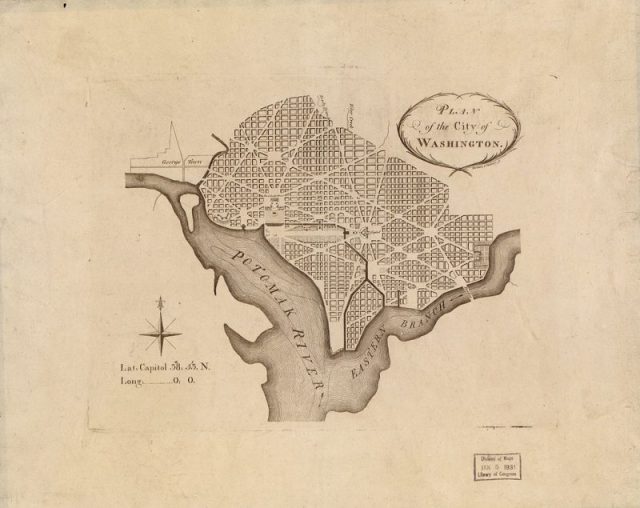

Introduced in 1789, the Constitution of the United States provided for the development of a new city that would act as the federal district of the nation. Later named after the first president himself, Washington D.C. was allotted up to 10 square miles. L’Enfant nominated himself to plan the city and George Washington accepted, officially appointing him to the task in 1791.

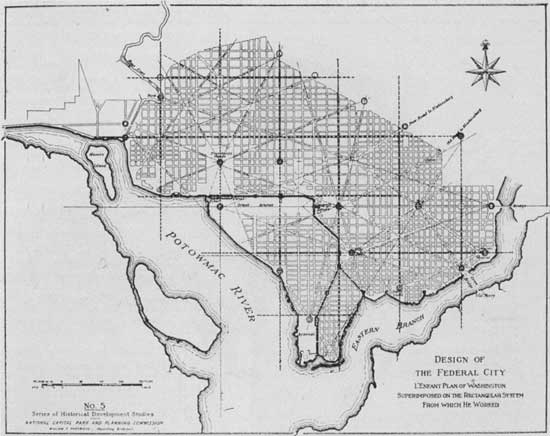

L’Enfant had grandiose ideas, taking inspiration from the architecture of his native France, wanting to reflect such palaces as the one at Versailles. In between the Potomac River and its Eastern Branch (today the Anacostia River), he developed a plan for the city that would compliment the contours of the land. L’Enfant’s biographer, Scott Berg, claims that, “The entire city was built around the idea that every citizen was equally important,” explaining why Congress was placed on the highest point overlooking the Potomac, traditionally an ideal location for the executive palace. In his Plan of the City […] L’Enfant described this location as “a pedestal awaiting a monument.”

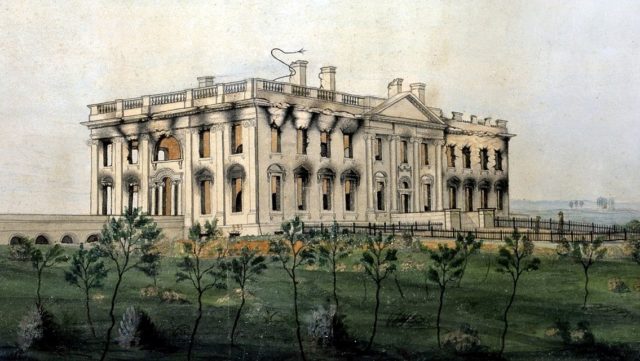

The President’s House, or Executive Palace (today the White House), was meant to be five times its actual size. Many of L’Enfant’s plans didn’t come to fruition at the time, however, including his development of the federal city. Urged by Thomas Jefferson, L’Enfant ended up resigning his post.

Throughout the project, the temperamental French architect clashed regularly with city commissioners worried about the budget, local wealthy landowners whose residencies were demolished for the development of the city, and real estate firms looking to buy land which would impede L’Enfant’s vision.

The Frenchman gained a reputation for an inability to work well with others. He also left the project to develop Paterson, New Jersey as well as the construction of Fort Washington, being replaced by less stubborn visionaries. This pattern would continue throughout the rest of his life.

Washington D.C. remained incomplete 110 years after L’Enfant’s resignation. In 1901 the McMillan Commission was formed by the Senate to complete the city, whose development continued based on the original and disputed plans of L’Enfant.

The Commission saw to the completion of L’Enfants dream of the National Mall: an open-air space designed to be accessible, emphasizing the country’s democratic and egalitarian values. They were unable to, however, realize his plan for a waterfall on Capitol Hill.

Peter L’Enfant, having anglicized his name in honor of his adoptive country, died in poverty in 1825. Originally buried at Green Hill Farm in Maryland, his remains were exhumed in 1909 and relocated to the Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia. His final resting place overlooks the Potomac River and the United States capital that he designed.

Today, the chairman of the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), John Cogbill, asserts that the NCPC accommodates L’Enfants original plan into all their work in Washington D.C. These plans are today guarded by the United States Library of Congress.