In today’s modern, industrialized world, there’s a certain number of things we take for granted without really considering the fact that they weren’t always around.

Taphophobia is the fear of being buried alive. This fear joked about in T.V. sitcoms and over-the-hill birthday cards has always existed. And with good reason.

Scientific development has traveled light-years since the 20th century. Before more modern times, taphophobia was a valid fear. Doctors, scientists, and specialists of the highest esteem spent centuries trying to curtail this fear.

The folk tale of The Lady With the Ring has versions told throughout history and across the world. In British folklore, it tells the tale of the Lady Mount Edgecombe who fell ill and was buried, presumed dead.

A grave robber took advantage of this unfortunate affair by trying to dig her up shortly after the burial in order to steal an invaluable ring she was buried with. Lady Mount Edgcombe awoke, however, and walked home, surely scaring the grave robber to death (although there’d be no way to check).

For some reason, the Victorian Era saw a rise in an obsession with taphophobia and inventors clamoring to find a foolproof way to confirm actual death before burial. Here are a few bizarre methods they came up with, as well as some veritable precursors to modern technology.

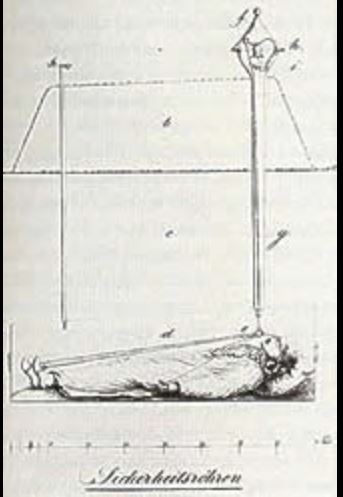

Safety Coffins

Safety Coffins are a popular historical fun fact shared for decades: the idea being that if someone mistakenly pronounced dead wakes up to find themselves buried, they simply pull on a cord linked to an above-ground bell that alerts cemetery workers that a mistake has been made.

More gruesome than the thought of waking up to find oneself in such a situation is the fact that an actual dead body swells during decomposition, meaning it could accidentally trigger the bell and a false alarm. No wonder people believed in ghosts.

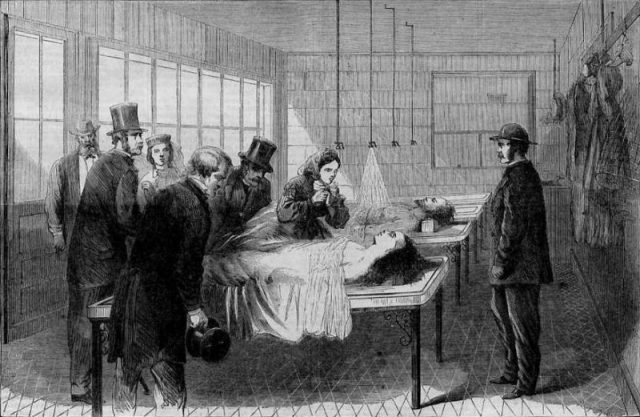

Waiting Mortuaries

Waiting Mortuaries were built and inadvertently became a morbid spectacle for our ancestors. At the end of the 19th century in France and Germany, corpses were laid out to wait and see if they started to decompose before being buried.

They were surveilled full time by morgue attendants and some were built with windows looking out onto the public who could stop and stare. The bodies were administered antiseptics to prevent infections, just in case they were still living.

It’s also thought that these Waiting Mortuaries began the tradition of sending flowers to funerals, as flowers were used to decorate the bodies to cover up the smell of the dead bodies in a time before Oust.

From here, the tactics get more invasive and, sometimes, questionable.

The finger

A body part thought to be a clue to real or falsely declared death was the finger. Some believed that holding the tip of a body’s finger to a strong ear would reveal even the faintest heartbeats.

According to the Dictionnaire biographique international des écrivains published in 1902, Dr. Collongues was a celebrated medical inventor responsible for the dynamoscope — a device which measured vibrations from living beings — and the necroscope — a device which assured a certain declaration of death based on the lungs, the heart, and the brain.

Though neither invention carried on to modern times, Collongues was on the path to the right idea and heartbeats were beginning to be linked to new inventions.

The Tongue

Others believed the tongue was the key. One suggested that an undead body could be stimulated by applying certain reactive substances on the tongue, such as a bitter lemon, sour vinegar, or alcohol.

Doctor J.V. Laborde in France was noted for studying the tongue’s relationship to death and allegedly claimed that he revived a woman thought to be dead by attaching forceps to her tongue and pulling at it for hours until she woke up. Surprisingly, designs for a tongue pulling machine didn’t come to fruition.

Moving up the intensity scale, one proposed method of certifying death was based on the new concept of the circulatory system. The idea of causing pain to a body to prove death was tried in several ways: holding the body’s finger over a burning candle, pouring boiling water on the body, or amputation of smaller body parts like fingers and toes.

Some scientists at the time believed that corpses wouldn’t blister under fire. One even insisted that raking thorny leaves over a body would produce a rash only if the person was truly dead. All evidence that science than had no certain knowledge of the inner workings of the human body.

Invisible ink played a role in the mortuary sciences as well. Not a new technology, this secret method of communication existed since ancient Greece. Victorian forensic scientists came up with the method of leaving notes declaring, “I am really dead” under noses.

If the person was really dead, the corpse would release sulfur dioxide through the nostrils which would trigger the invisible ink. Unfortunately rotting teeth in an era of poor dentistry could give a similar effect.

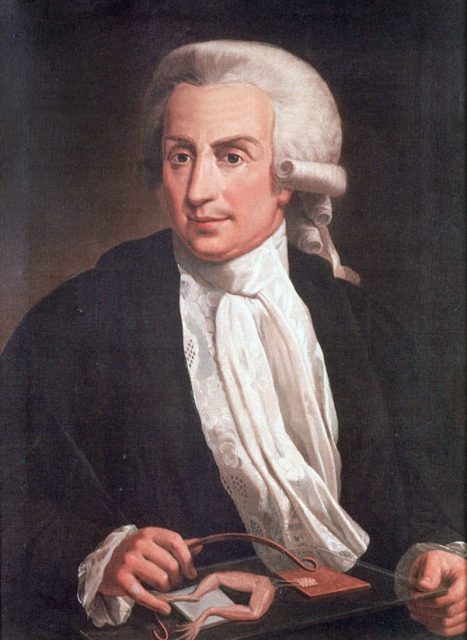

The closest “Victorian” method to our present-day confirmed methods was Galvanism. Luigi Galvani pioneered the field of bioelectromagnetics as early as 1780 when he applied electricity to animal corpses. Along with his wife, Galvani played the role of the Italian Dr. Frankenstein, researching the relationship of electricity with muscles and nerves. A precursor to the defibrillator.

It’s true, Galvani existed before the Victorian Era, but perhaps later scientists should have paid a bit more attention to his work. Instead, a couple of decades passed with questionable and regularly unreliable methods of certain death confirmations.

Scientists’ false claims of success to protect their own hubris and ghost stories during God-fearing times kept taphophobia alive over the centuries when doctors were working on methods to confirm the death.

Lucky today that we know what a coma is, know how to measure heartbeats, and won’t wake up to less finger and toes.