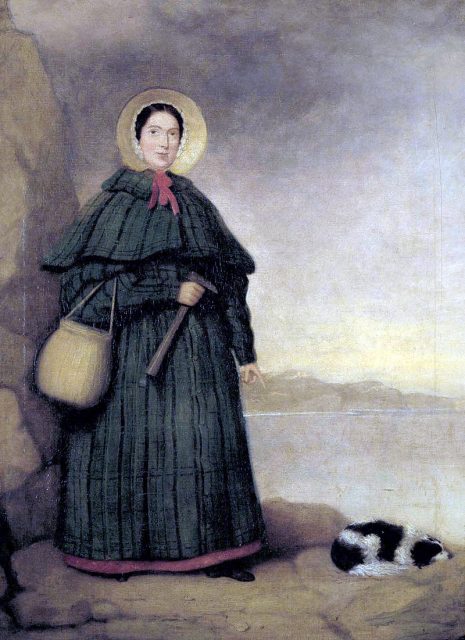

The name of Mary Anning has been virtually erased from the history of science, despite the fact that this industrious woman made a fundamentally important contribution to the developing field of paleontology in the 19th century. She was responsible for uncovering some of the most significant finds of the era, yet she received little recognition in her own lifetime. However, renewed interest in her life and work is ensuring that the reputation of this oft-overlooked fossil hunter is being restored.

A new film, Ammonite, starring Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan, is due to be released in 2020, and will focus on the later years of Mary’s life. Although the story is fictionalized, it is hoped that it will call attention to Anning’s forgotten contribution to science and paleontology.

Mary Anning was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, on England’s Jurassic Coast, famous for its rich concentration of fossils. According to the Natural History Museum, she was born into humble circumstances, to a family of Congregationalists — religious dissenters who had turned away from the Church of England. Her family lived in difficult circumstances and only one of her eight siblings, Joseph, survived to adulthood.

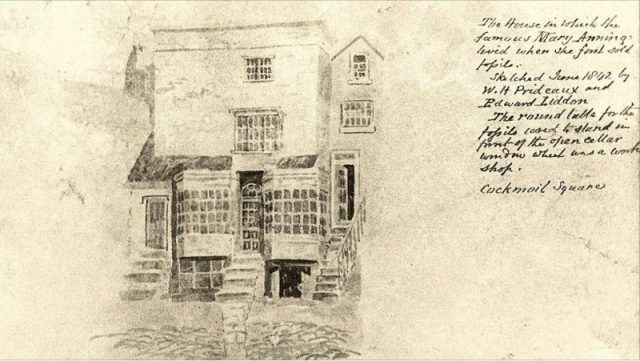

Anning’s father was a cabinet-maker and an amateur fossil collector. The abundance of fossils along the Jurassic Coast, the result of a geological formation known as the Blue Lias, offered a lucrative opportunity for sharp-eyed residents seeking to supplement their income.

Interest in fossils, stones and other “curios” was increasing among the middle class visitors who came to pass their holidays in Lyme Regis, and Anning’s father knew he could sell the family’s finds in his shop.

Unusually for a girl of her class and age, Anning was literate, having received an education through the Congregationalist church to which her parents belonged.

However, she had little formal education in science and geology, and had to acquire her specialist knowledge herself. According to the Natural History Museum, she applied herself to her passion and soon became an expert in seeking out, extracting and identifying fossils.

Anning’s skills became even more important when her father died suddenly in 1810, when Anning was just 12-years-old. In order to help the family survive, she continued to find and sell fossils. Her work would lead her to some of the most remarkable discoveries of the era, which transformed our understanding of the prehistoric world.

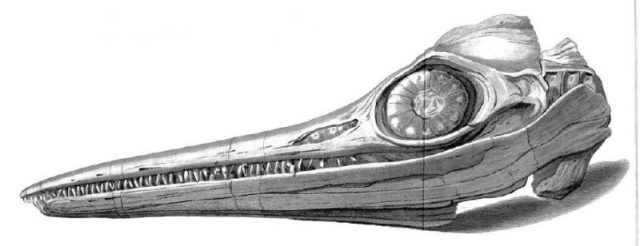

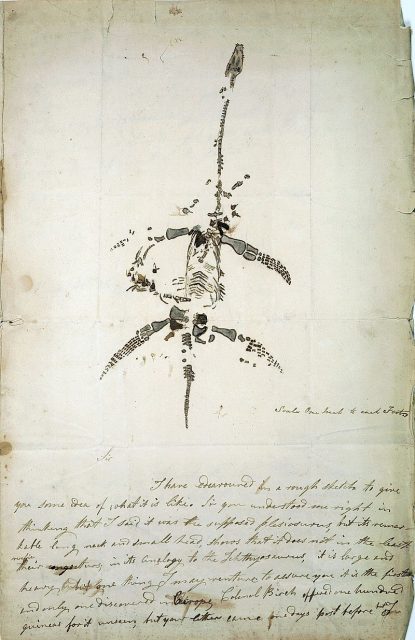

In 1811 she uncovered the 17-feet-long (5.2-meter) skeleton of an ichthyosaurus. The find, the first of its kind, caused an intense amount of speculation concerning the origins and nature of the creature that had once apparently roamed the English coast. In 1823, she uncovered the complete skeleton of a plesiosaurus, a discovery that once again caused a commotion in the scientific community.

According to the Natural History Museum, many leading scientists, including the renowned paleontologist Georges Cuvier, assumed the fossil to be a fake. It was finally authenticated and Cuvier was forced to admit his mistake. In addition, in 1828, she uncovered the first Pterosaur found outside Germany, now known to be the remains of a dimorphodon, an enormous winged creature believed to be one of the largest ever flying animals.

Anning continued to unearth incredible fossils and skeletons. She extracted, cleaned and identified them, and then sold them on to scientists or collectors with an interest in paleontology, who would then display them in museums and public collections.

However, she was seldom credited in the work of these scientists, who neglected to attribute the finds to her. As a result, it is only recently that historians have begun to understand the extent of her contribution to the burgeoning field of paleontology. The lack of recognition given to her work meant that Anning lived a life in relative poverty, constantly struggling to make ends meet.

She died in 1847 at the age of just 47, as a result of breast cancer. For many years, her name did not feature among the great pioneers of science, geology and paleontology.

Read another story from us: Female Mummy Hunters and the Remarkable Impact They Made

However, as we continue to learn more about her life and work, the legacy of this remarkable, tenacious woman is being restored to its rightful place in history.