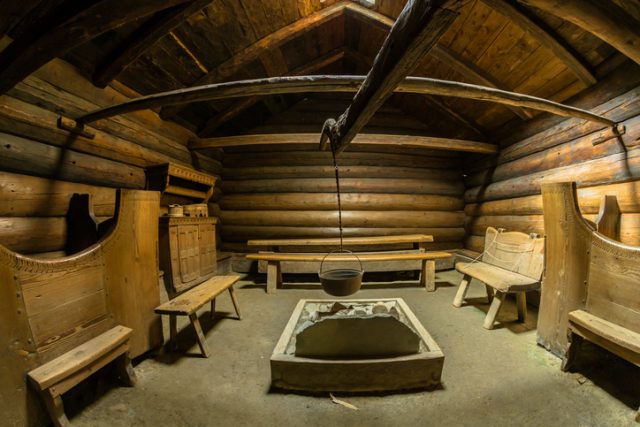

The Old Norse home wasn’t a retreat from the outside world, it was a microcosm of the outside world. The same complex beliefs which governed the society of Viking Age Scandinavia continued even when the Norseman had shaken the snow from his boots, rested his sword by the fireplace and shrugged the fur cloak from his shoulder.

The main reason for this is that Viking Age homes were communal. They weren’t just the center of the community, they were communities in themselves with the patriarch at the heart of the family unit, surrounded by his closest relatives, his loyal retainers and warriors, and then finally his thralls, little more than slaves who had no legal rights and could be abused and exploited at will.

Life was governed by status, and status was found at the head of the table and closest to the fire. But the home was a spiritual place too and the relationship between its architecture and its occupants often continued posthumously.

In the Icelandic Laxdæla Saga, compiled from 9th to 11th-century folk tales and oral histories in the 13th century, as he lays dying the violent Hrapp, known as “Fight Hrapp”, demands to be buried in the doorway to the fire hall. He asks that he be interred upright so he could keep watch over the home.

The story of Hrapp may sound like a pure fairy tale, but archaeological investigations of Iron Age and Viking Age homes in Scandinavia have uncovered human bones within the house, including the remains of infants under the hearth, the floor of the fireplace, and postholes, as if they kept watch over the liminal spaces in the home — the places between the household and the outside world.

Related Video: 10 Fascinating Viking Facts

In Hrapp’s case, his role wasn’t entirely benign. He not only kept watch over his family home, but rose from the dead and, according to the saga, did away with most of the family’s servants. The haunting only abated when his remains were dug up and he was reburied far away.

Liminal spaces, such as doorways, weren’t just portals between different spaces of the physical world, but between the physical and the spiritual world too. The dead, then, could function as spiritual guardians, or, if their motives were less than pure-hearted like the notorious “Fight Hrapp”, use them to walk between the realm of the living and the realm of the dead.

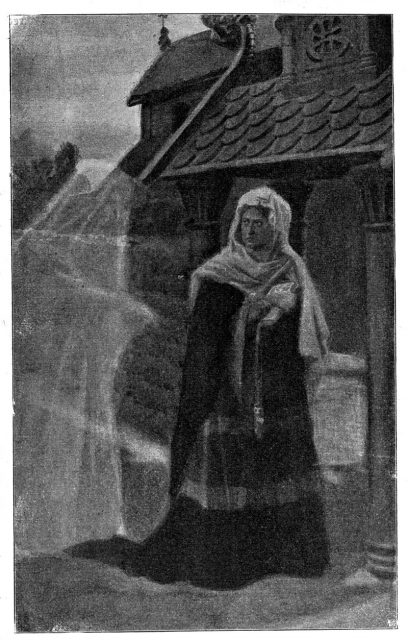

There are historical records of women being lifted up so they could gaze “over” the doorframe at the world beyond, whether seeing into the future or communing with the dead. The role of doors as portals to the afterlife existed independently of the home, and free-standing doorways were erected at Viking Age burial grounds to allow seers to commune with their ancestors.

The later Icelandic Grettis Saga, compiled sometime before the year 1400, tells of our hero, Grettir being forced to confront the cursed shepherd Glamr, who becomes a draugr — an animated corpse with superhuman strength and the unmistakable stench of decay.

Glamr is described as knocking the doorframe down as he flees the house. This is not only a sign of his immense strength but of his breaking through between the worlds of the living and the dead. As with Hrapp’s ghost, the only solution to Glamr’s reign of terror was to incinerate his remains and scatter the ashes as far from human habitation as possible.

A similar trope of the draugr in the doorway appears elsewhere in Norse folklore. In the Icelandic Flóamanna Saga, set over the 9th to 11th centuries and compiled at the end of the 12th or beginning of the 13th, a draugr knocks on the door to gain entrance, similar to one of the popular myths associated with vampires, that they have to be invited before they can cross the threshold. Anyone who answered the door to a draugr not only unleashed the beast into their home but was said to go mad and rise as a draugr themselves — suggesting that the portal to the afterlife was very much a two-way street.

Objects — such as iron pots, knives or rings — were also found buried under the hearth or postholes, leading historians to suspect that they too played a magical role, either protecting the home or linking it to its new owners.

Read another story from us: Viking Ship Discovered in Norway

The Norse world was spread from Greenland to the Black Sea, and the Viking Age lasted 273 years from approximately 793 to 1066 AD, so traditions varied. However there’s evidence that items were deposited throughout this period to mark occasions in the home’s “life” — such as construction and rebuilding, births, marriages, and deaths, or the house finally being vacated.

Rather than being a sanctuary or a haven, the Norse home could be just as dangerous as the outside world and its occupants had to be prepared for all dangers, even if they came from beyond the grave.