Artificially elongated skulls discovered in Hungary have offered valuable evidence of life during the Roman Empire’s collapse. People in different cultures and countries put themselves through a whole lot of physical changes — cosmetic or otherwise — in an attempt to conform to their society’s standard of beauty. The practice of foot binding in China comes to mind, or the American obsession with plastic surgery to “improve” appearance.

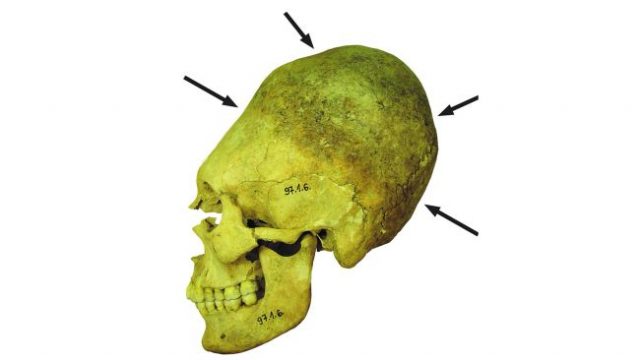

But skull binding? Though the practice may sound odd and even cruel, it was in fact quite common as far back as the Paleolithic era in areas of central Asia. It then became popular in central Europe around the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. , and remained popular until about the middle of the 5th century A.D. Recently, experts’ examination of elongated skulls found in a Hungarian cemetery over the last several years has led to new insights into how communities were formed after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Some of the skulls are approximately 1,000 years old, and are part of sets of remains found in one burial site, but represent three separate communities that shared customs. Skull binding is one of those customs, a tradition that began in childhood, scientists said. New technology, known as isotope analysis, allowed these experts to understand the links between what were previously thought to be people of separate origins, and how they formed communities. Results from the study were published in the April 29th edition of the online scholarly journal, Plos One.

The first group of remains were found in graves of the common Roman tradition; the second were of a group of people who came from outside that community, while the third bore similarities of both. One obvious link between all three sets of remains were skulls bound and lengthened. There is no evidence that the practice was harmful, but rather a custom related to standards of attractiveness of the time.

The new technology also allowed experts to examine more closely and learn about the dietary habits and lifestyle choices of these people in the 5th century. Realizing never before known facts about the three groups meant that researchers learned they moved, rather than simply living and dying in one place, as previously thought.

Furthermore, the isotope analysis technology was able to give them a better understanding than using only traditional archaeological methods. Different people, with different backgrounds and origins, not only came together in one location, but apparently lived together peacefully and chose to share a cemetery. They would not have been buried in the same place if they did not share many cultural traditions and customs — like skull binding.

It’s also known as head binding, a form of body modification that, until relatively recent times, was surprisingly commonplace right around the world. Scientists say it does no harm to the brain itself, as the volume of brain matter within the skull remains unchanged. It is simply the skull, the vessel that holds the brain, that is altered.

An infant’s head was bound not long after birth because that was when it was at its most malleable, and therefore took less time to elongate, but in no way did it wound or impact the brain, or harm the growing intellect of the baby. At the cemetery in Hungary, which scientists say was abandoned in 470 A.D. experts examined more than 50 sets of remains. The cemetery was once in a Roman province called Pannonia Valeria, and it contained almost 95 burial sites.

Skull binding is indicative of a custom we may find at the very least weird today, but in a sense it is no different than other body modification styles, like piercings and tattoos. Since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it was clearly thought of as a way to enhance attractiveness once, all those centuries ago.

Related Article: Actual head cone found on buried Egyptian woman solves ancient Mystery

Perhaps what is more important is the teachings of the study, which confirmed that, although people came from different places, they were able to adjust happily to one another and live in a shared space. And they were so comfortable together they even shared the final space — a graveyard.