The rare Queen Alexandra’s birdwing, or Ornithoptera alexandrae, can reach wingspans of nearly 12 inches across, but the largest butterfly species on Earth could be gone before the majority of people have the chance to glimpse it. These elusive beauties have a history just as fascinating as their biology.

Discovering the world’s largest butterfly

Queen Alexandra’s birdwing was first discovered in 1906 by naturalist Albert Stewart Meek, who was employed by British banker and zoologist Walter Rothschild and charged with finding new butterfly species in Papua New Guinea. Meek documented his adventures in a 1913 book, which included his bizarre methods of capturing specimens to bring home to study.

While the local Indigenous people of Papua New Guinea used nets made from spiderwebs and sticks to safely capture the fragile butterflies, Meek took an entirely different approach – shooting the large insects out of the sky with a gun loaded with special ammunition to cause as little damage as possible. Most of Meek’s specimens still preserved today are dotted with bullet holes.

One day Meek spotted a large butterfly in the forest and shot it down to bring home to Rothschild. Rothschild examined the specimen and prepared a scientific description as well as a name: Queen Alexandra’s birdwing, after the newly coronated Queen of England, Alexandra of Denmark, the wife of Edward VII who succeeded Queen Victoria.

The incredible but short life of the Queen Alexandra’s birdwing

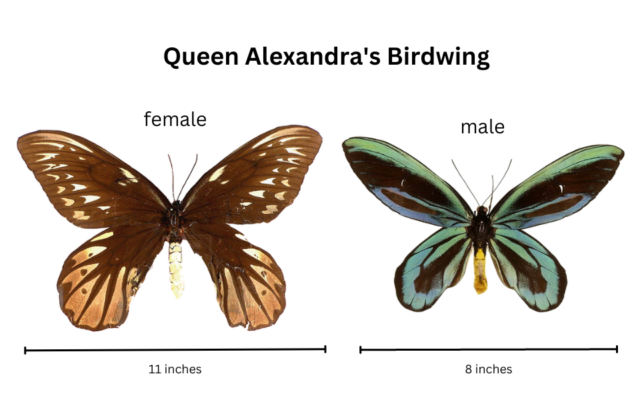

It’s no wonder that this butterfly is named after a queen and not a king. Female Queen Alexandra’s birdwings grow much larger than males, reaching wingspans of up to 11 inches and a body length of 3.1 inches. Males, on the other hand, are smaller but have more vibrant coloration and more angular wings. The male butterflies have bright yellow abdomens and a wingspan of up to eight inches.

The butterflies participate in a mating ritual where the male hovers over the female high up in the rainforest and drizzles them with pheromones which will induce copulation. If the female accepts the male’s invitation, mating can begin. Males are extremely territorial during this process, fending off potential rivals including other birdwing butterflies and even small birds.

A female can lay up to 240 eggs during her lifetime, which once laid will become larvae that hatch out of their shell and begin the first part of their lives as caterpillars.

The caterpillars feed on the leaves of the pipevine plants that they are typically laid on as eggs. These types of plants contain aristolochic acids which are poisonous to vertebrates like birds and other predators, helping to keep the caterpillars from getting eaten. Once the caterpillars reach maturity, they create a thick skin which becomes the pupa, or chrysalis. For the species to develop from egg to pupa, it takes six weeks of constant eating before they live inside the chrysalis for a month or even longer as they transform into butterflies.

The fully formed adult butterflies will emerge from their pupa in the morning while the air is still humid. This gives their wings plenty of time to expand before they dry out. Finally, the entire ordeal is complete, and the butterfly will go on to live another three or four months – just enough time for them to lay its own eggs and start the process all over again.

The butterfly is currently facing extinction

The Queen Alexandra’s birdwing is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as it is restricted to a small, 40 square-mile patch of coastal rainforest near Popondetta, Papua New Guinea. This butterfly has always been rare due to its traditionally small area of habitat, but the Queen Alexandra’s need for old-growth rainforests has intensified concern for the species’ survival.

In 1992, experts did a survey of the species only to count 150 Queen Alexandra’s birdwings in a 10-day period, revealing a shocking decline in their population. Those numbers dropped again in the mid-2000s, and by 2008 only 21 adult butterflies were found over a three-month-long study period.

But why exactly are their numbers so small? Currently, a large portion of the Queen Alexandra’s birdwing’s territory is under siege by deforestation from palm oil plantations. A volcanic eruption in the 1950s also wiped out a large area of the species’ former habitat.

The Queen Alexandra’s birdwing is highly prized on the butterfly black market

The Queen Alexandra’s butterfly is listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES, which bans all international commercial trade of the species.

Because of its rarity and size, this butterfly species is highly prized by collectors who purchase them for upwards of $10,000 US dollars on the black market. In 2007, a “global butterfly smuggler” named Hisayoshi Kojima was charged with 17 counts of selling endangered butterflies – including a pair of Queen Alexandra’s birdwings – to a special agent from the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

More from us: The Ancient Tully Monster Was So Unusual That Scientists Still Don’t Know How to Classify It

It could only be a matter of time before the world’s largest butterfly is gone forever, though we hope that continued conservation efforts will help to stabilize their population to preserve this incredible species for future generations to see.