A new article has reported that a cave found outside Jerusalem may have been used for cult practices, including trying to communicate with the dead. The strategic placement of specific artifacts within the cave suggests this, in addition to the number of human skulls found alongside them.

The caves have been researched in the past

The Te’omim cave system is not a recent discovery. In fact, it was first found and explored in 1873 by explorers Claude Reignier Conder and Herbert Kitchener. Although they were the ones who identified the cave system, they did not explore its depths.

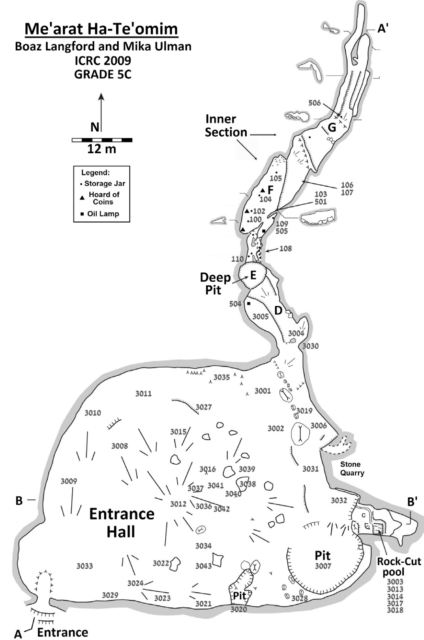

It wasn’t until the 1920s, when René Neuville and a team of archaeologists began exploration, that a more thorough understanding of the cave system was established. It consists of a large main chamber that leads to a pit on the northern end. Within, they found wooden, stone, and ceramic artifacts that have been dated to several time periods, including the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, the Iron Ages, and the Roman and Byzantine periods.

While the cave system was used by a number of different groups over the centuries, its most recent history seems to have changed the function of the natural space. A new study suggests that it became a “place of devotion” for the purpose of necromancy, or communication with the dead.

Oil lamps have a significant meaning in necromancy

One of the main signals for researchers was the discovery of more than 120 preserved oil lamps systematically placed all around the cave system. Between 2010 and 2016, these lamps were discovered in various cracks and crevices throughout the area, alluding to their potential function.

“The fact that these lamps had been thrust into and buried deep in these hidden, hard-to-reach crevices suggests that illuminating the dark cave was not their sole purpose,” the authors report in the study. Instead, they believe the lamps were used “as part of a cultic activity.”

“The use of oil lamps for divination … was extremely widespread in the classical periods,” the study said. “The prophetic force behind the lamp was believed to be a spirit or spirits, or in some cases even gods or demons.” Messages would come through the flames of the lamps. “Divination by means of oil lamps was done by watching and interpreting the shapes created by the flame.”

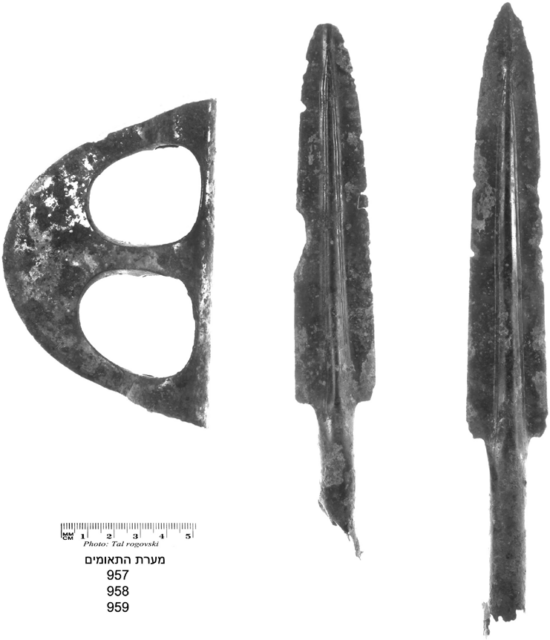

Metal weapons were needed for protection against evil spirits

Interestingly, several weapons made of bronze were found within the cave system. The study explains that these were kept close to those who entered the cave for divination. “They served primarily to protect the believer from evil spirits and to ensure that offerings to the specific spirit being conjured up were not seized by other spirits.”

It was believed that spirits were afraid of metal, particularly iron and bronze. As such, keeping a metal weapon close by, such as a sword or dagger, would keep you somewhat protected from evil spirits.

Also found in the cave system were multiple human skulls. The study states, “Due to the archaeological context of the finds and their location inside the cave, we assume that the craniums were placed together with the oil lamps as part of a ritual of magic.”

While it is of course difficult to pinpoint the exact purpose of the human skulls, it is a safe estimate that they were used in a similar fashion to skulls found throughout the former Roman Empire which were employed for “necromancy ceremonies and communication with the dead.”

The caves may have been used as portals to the underworld

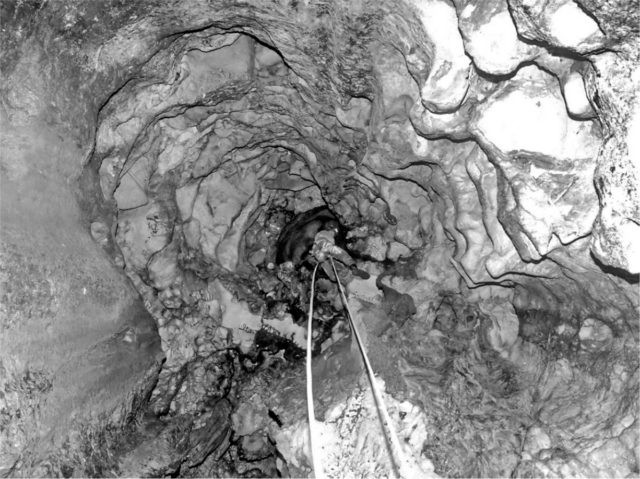

The study suggests that the cave system was associated with tales of Persephone, providing a portal to and from the underworld. The shaft located in its depths provided a gateway “through which the dead could rise.”

In order to perform their necromancy ceremonies, witches needed an “oracle of the dead,” which was typically a shrine located in caves near a source of water. It was the water that served as the portal to the underworld.

“Their purpose was to predict the future and conjure up the spirits of the dead. Because more than 100 ceramic oil lamps but only three human skulls have been found so far in the Te’omim Cave, we hypothesize that the primary cultic ceremony focused on depositing oil lamps for (underworld) forces, perhaps as part of rituals conducted in the cave to raise the dead and predict the future.”

More from us: 2,000-Year-Old Ancient Roman Hoard Discovered by Metal Detectorists in the UK

“In light of all this, we can propose with due caution that necromancy ceremonies took place in the Te’omim Cave in the Late Roman period, and that the cave may have served as a local oracle (nekyomanteion) for this purpose,” the study concluded.