Cons take place every day all over the world. Today, it seems easier than ever for a rip-off artist to send a phishing email or a text, pretending to be someone else or some company, in hopes that the recipient is gullible enough to respond and share some useful details.

In the 1920s, however, one scam artist played two cons so big that they became legendary. Building on the small scams he had run in his youth, this man baited his victims into purchasing the Eiffel Tower – not once, but twice. This is the true story of Victor Lustig, the man who sold the Eiffel Tower.

A life of crime

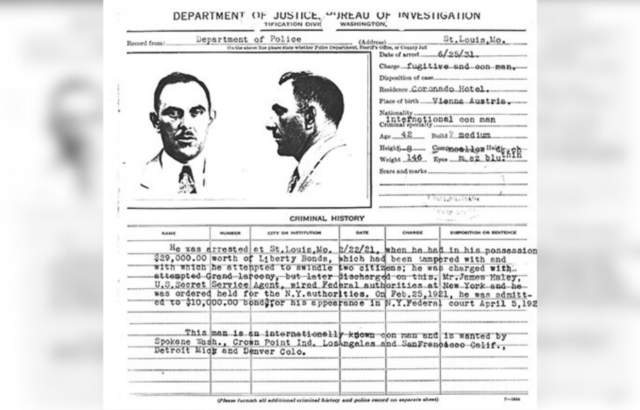

Victor Lustig was born in Austria-Hungary in 1890. He went to school in Paris, which is where he embarked on his life of crime. After he left school as a smooth-talking, witty, and attractive (despite the scar on his cheek from a woman’s jealous boyfriend) young man, fluent in several languages, he had all the makings of a professional confidence trickster.

Some of his initial cons took place aboard luxury liners sailing between French and American ports. While aboard the ships, Lustig would gain the trust of the wealthiest passengers. When they inevitably asked where he made his fortune, he would confide in them that he printed bills with a ‘money box’ he kept in his cabin.

Naturally, these passengers would want to see this incredible device. Lustig would invite them into his cabin and show them the machine, which printed $100 bills. The only issue with the machine was it took six hours for a single bill to be printed. Lustig would invite his guests back six hours later, showing them the bill coming out of the machine, and again six hours later as another crisp $100 bill was being printed.

Seeing the production of two $100 bills that looked legitimate in every way inevitably had the passengers asking how much to buy one. Lustig would, after a bit of negotiation, sell the boxes for anywhere between $10,000 and $30,000, with one allegedly fetching $47,000. The unfortunate passengers who bought a machine would soon realize that it only produced two actual bills, which were placed into it by Lustig himself. But by that time, he had disappeared with their money.

Selling the Eiffel Tower

If someone asked you if you’d like to purchase the Eiffel Tower, you’d either think that it was a scam or that they were crazy. You may try to rationalize it by thinking they meant an Eiffel Tower souvenir. You most certainly wouldn’t actually think you could buy the real one. In 1925, however, this was more believable than it is today.

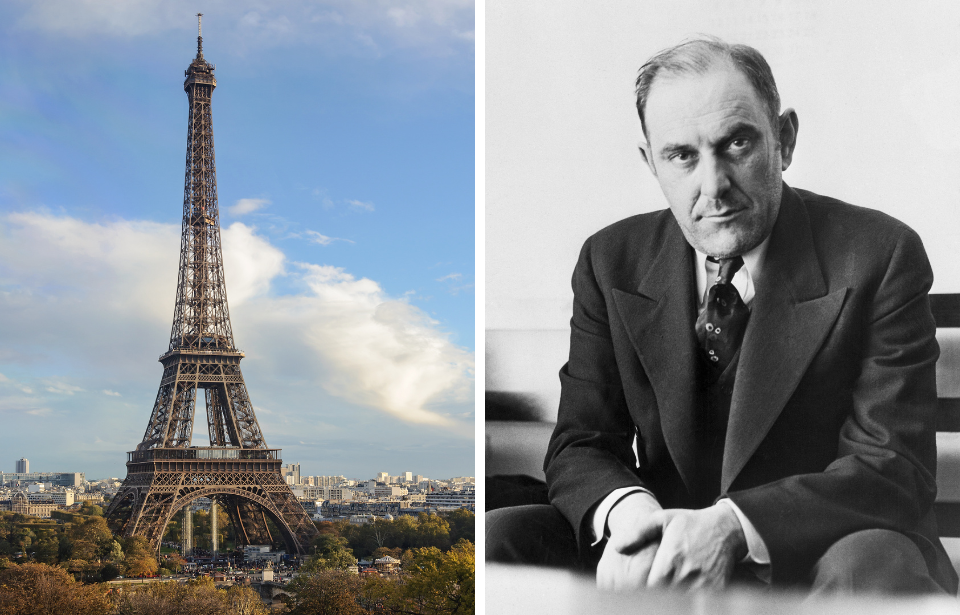

The Eiffel Tower, named for its designer, Gustave Eiffel, was built on the Champ de Mars in Paris. Constructed between 1887 and 1889, it was the pièce de résistance of the 1889 World’s Fair. It has since become a symbol of France. But, in 1925, it was reported that the government had been spending far too much money to maintain the tower, which had fallen into disrepair. Lustig then thought of his grandest con.

A newspaper article stated that some people were calling for the Eiffel Tower’s removal instead of keeping it. Lustig then made fake government papers and invited scrap metal companies to attend a meeting at a beautiful hotel. Once there, he said that he was the Deputy Director-General of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs.

Lustig told the businessmen that the Eiffel Tower cost far too much and ultimately didn’t fit in with Paris’ other landmarks, such as the Arc de Triomphe. During this meeting, he focused on André Poisson, a young businessman whom Lustig had identified as eager to climb up the ranks of the business world and perhaps a little insecure where he currently was.

Lustig invited Poisson to a private meeting. There, he convinced him that he was a corrupt government minister and that if Poisson paid Lustig a bribe, then Poisson would be selected as the new owner of the Eiffel Tower. Believing that this would give him the position he wanted, Poisson agreed and paid Lustig a sum reported to be about 70,000 francs.

Hoping to ensure that the authorities wouldn’t catch him, Lustig left with the money and went to Austria. However, Poisson seems never to have told the police of the transaction, likely due to the shame and scandal it would have caused. Naturally, Lustig decided about a year later to return to Paris.

Upon his return, Lustig began the scam again. Initially, it seemed to be working; however, one of the six new scrap dealers he had invited to a meeting had a strange feeling about the deal and told the police. Just in the nick of time, Lustig boarded a luxury liner en route to the United States as the authorities began to look at him as a suspect.

The crime didn’t stop there

Lustig’s close call with the law didn’t dissuade him from continuing his criminal endeavors. Upon returning to the United States, he dove headfirst into a life of crime, fueled not only by monetary gain but also by the thrill of outsmarting others. He even tried to con the notorious gangster Al Capone in 1925.

He arranged a meeting with Capone, then 26 years old, at a Chicago hotel. During their encounter, he persuaded Capone to invest $50,000 in a get-rich-quick scheme, promising to double the amount within 60 days or less. It’s said that he returned the entire amount to Capone 60 days later, saying that his big deal had fallen through. Capone, impressed with this “honesty” and believing Lustig’s story that he was broke, gave the conman $5,000 to invest. Lustig pocketed the cash as he skipped town.

He also started a large-scale counterfeiting operation that lasted almost five years, although it eventually caught the attention of federal agents.

Lustig was arrested in New York on May 10, 1935, and charged with running a counterfeiting operation. His mistress had learned he was cheating on her and turned him in to the authorities. He was sentenced to 20 years at Alcatraz Island prison.

More from us: Sources Say ‘Catch Me If You Can’ Fraudster Frank Abagnale Jr. Lied About His Life

Victor Lustig died in a prison hospital on March 11, 1947, after contracting pneumonia.