The high point of the RMS Olympic‘s career was on May 12, 1918, when it intentionally rammed and sank the German submarine U-103, which attempted to torpedo the Olympic.

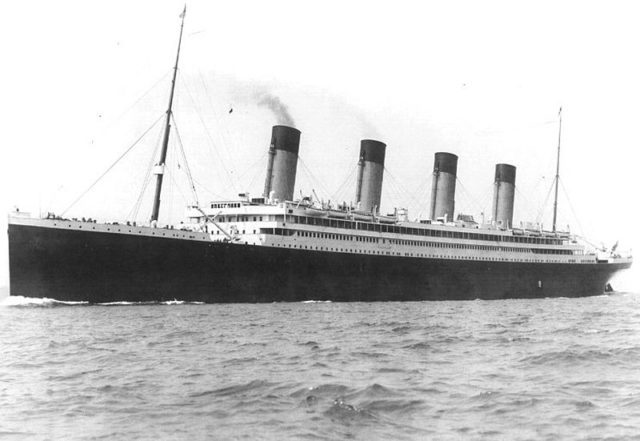

The USS Davis rescued the Olympic’s survivors. In the beginning, the Olympic was a commercial ship under Captain Herbert James Haddock. WWI had started in 1914.

Since it was wartime, the ship was painted gray, the portholes were blocked off, and the lights on the deck were turned off to make the ship less likely to be noticed.

The schedule was quickly altered to not terminate at Southhampton as usual but to go ahead to Liverpool. Later, it was changed to Glasgow.

The ship’s first wartime voyages had the Olympic packed with Americans who were anxious to get home after having been trapped in Europe since the start of the war.

Even though there were some passengers on the eastbound voyages, the bookings dropped off significantly by mid-October due to serious threats from German U-boats.

White Star Line made the decision to take Olympic out of commercial service.

Olympic left for New York on October 21st, 1914 traveling to Glasgow for her final commercial voyage of the war, but she only had 153 passengers.

Olympic took on the 250 Audacious crew members. HMS Fury attached a tow cable between Audacious and Olympic so they could all head west toward Lough Swilly.

The cable parted not too long after the steering gear on the Audacious failed.

A second attempt was made to tow the ship, but the cable got tangled in the propellers of the HMS Liverpool, and they were severed.

They tried for a third time, but the cable gave way.

At 5:00 pm, the quarterdeck of the Audacious was flooded, so the decision was made to evacuate the rest of the crew onto the Liverpool and Olympic. At 8:55 pm, an explosion on the Audacious sank the ship.

Not wanting to deal a blow to the British public, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander of the Home Fleet, wanted to suppress the news of the Audacious’ sinking. He ordered the Olympic to held in military custody at Lough Swilly.

No communications were allowed, and passengers could not leave the ship.

The only people allowed to exit the Olympic were Chief Surgeon John Beaumont and the crew from the Audacious.

Charles M. Schwab, the steel tycoon, sent word to Jellicoe that he was on his way to London for urgent business with the Admiralty.

Jellicoe decided to release Schwab if he agreed to keep quiet about the Audacious’ sinking.

The Olympic was allowed travel to Belfast on November 2nd so the passengers could disembark.

Once the Olympic made it to Britain, White Star Line was going to leave the Olympic in Belfast until the war was over.

In May 1915, the Olympic was requisitioned by the Admiralty to be used for moving troops.

The Aquitania and Mauretania, which were Cunard liners, were also acquisitioned.

Before this, the Admiralty had been reluctant to use larger ocean liner to transport troops because they were more vulnerable to enemy attacks. There was little choice because of ship shortages.

The Britannic, which was a sister ship to the Titanic and Olympic, it was requisitioned as a hospital ship even though she wasn’t completed. She hit a mine and sank the following year.

The peacetime fittings were stripped from the Olympic, and she was armed with 4.7 inch and 12 pounder guns. Olympic was made into a troopship with the ability to transport as many as 6,000 troops.

On September 24, 1915, the newly designated Hired Military Transport 2810, under Bertram Fox Hayes’ command. Left Liverpool carrying 6,000 troops headed to Moudros, Greece for the Gallipoli Campaign. On October 1, 1915, she saw lifeboats from Provincia, the French ship, which had sunk that morning off the coast of Cape Matapan, after a U-boat attacked it. She picked up only 34 survivors.

Hayes was criticized by the British Admiralty for taking that action and saving the 34 soldiers, saying he put the ship in danger since there were still active enemy U-boats in those waters.

Since the ship’s best defense against U-boats is its speed, and since the large ship had stopped in the water, it would have made an easy target.

Hayes was awarded a Gold Medal of Honor by the French Vice-Admiral Louis Dartige du Fournet for saving the 34 soldiers.

The Olympic made several voyages to the Mediterranean up until early 1916, when the Gallipoli Campaign ended.

When that ended, they thought about using the Olympic to transport troops by the cape of Good Hope to India.

After considering that further, it was decided that she wasn’t capable of such a role because her coal bunkers had been designed for transatlantic runs didn’t have the capacity that was needed to pursue such a long journey at a reasonable speed.

The Olympic was chartered by the Canadian government from 1916 to 1917 to transport troops to Britain from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

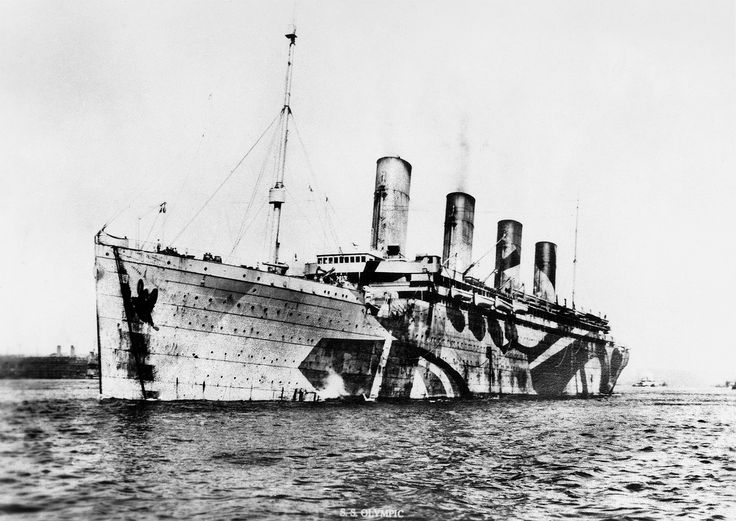

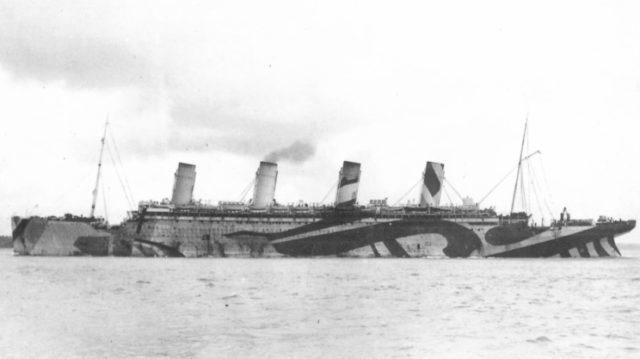

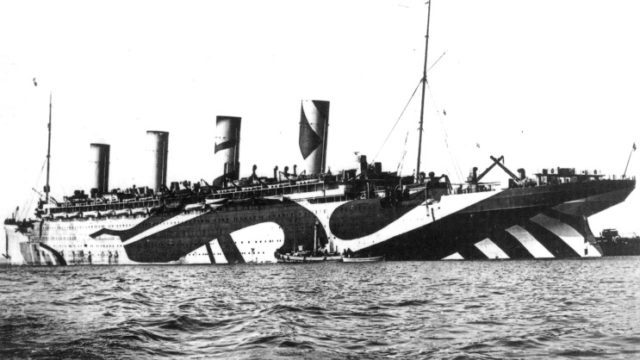

In 1917, she gained 6-inch guns and was painted with a camouflage scheme to make it harder for those trying to determine where she was headed or her speed.

The camouflage was dazzling with white, light blue, brown and dark blue.

Olympic made quite a few trips to Halifax harbor transporting Canadian troops overseas safely and back home after the war. The people of Halifax saw the Olympic as a favorite symbol.

The noted Group of Seven artist, Arthur Lismer, painted several artists of the Olympic in Halifax.

In 1917, after the U.S. declared war on Germany, the Olympic transported thousands of U.S. troops to Britain to aid in the war.

On May 12th, 1918, in the wee hours of the morning, under the command of Captain Hayes, the Olympic was in route to France with U.S. troops when a U-boat was sighted just 1,600 feet ahead.

Her gunners immediately opened fire, and she turned, ramming the sub, which immediately crash dived to 98 feet and turned a parallel course.

The Olympic struck the sub almost immediately near the conning tower with her port propeller slicing though the sub’s pressure hull.

The crew of the U-103 sub blew her ballast tanks, scuttled her then abandoned the sub right there.

The Olympic did not stop to pick up any survivors, but went straight to Cherbourg.

The USS Davis was the ship to sight the distress flares, and they stopped and picked up the 31 survivors from U-103.

The Olympic went to Southhampton with at least two dented hull plates and her prow twisted on one side, but it wasn’t breached.

Later it was learned, that the U-103 was going to torpedo the Olympic when it was sighed, but the crew could not flood the two torpedo tubes.

Captain Hayes was awarded the DSO for his service.

Several of the American soldiers on board paid for a plaque to be put in one of the lounges aboard the Olympic to commemorate the event.

The plaque read: “This tablet presented by the 59th Regiment United States Infantry commemorates the sinking of the German submarine U-103 by the Olympic on May 12th, 1918 in latitude 49 degrees 16 minutes north longitude 4 degrees 51 minutes west on the voyage from New York to Southampton with American troops.

During the war, the Olympic is reported to have carried up to 201,000 troops and other personnel, burning 347,000 tons of coal and travelling about 184,000 miles.

Her impressive World War I service earned her the nickname Old Reliable. Her captain was knighted in 1919 for “valuable services in connection with the transport of troops.”