King Tutankhamun is arguably the most famous Egyptian pharaoh of all time. In 1922, Howard Carter and his team of archaeologists found the greatest discovery of all time. Little did they know in the beginning that Carter and his team would find the intact tomb from the 18th Dynasty of a pharaoh known as King Tut.

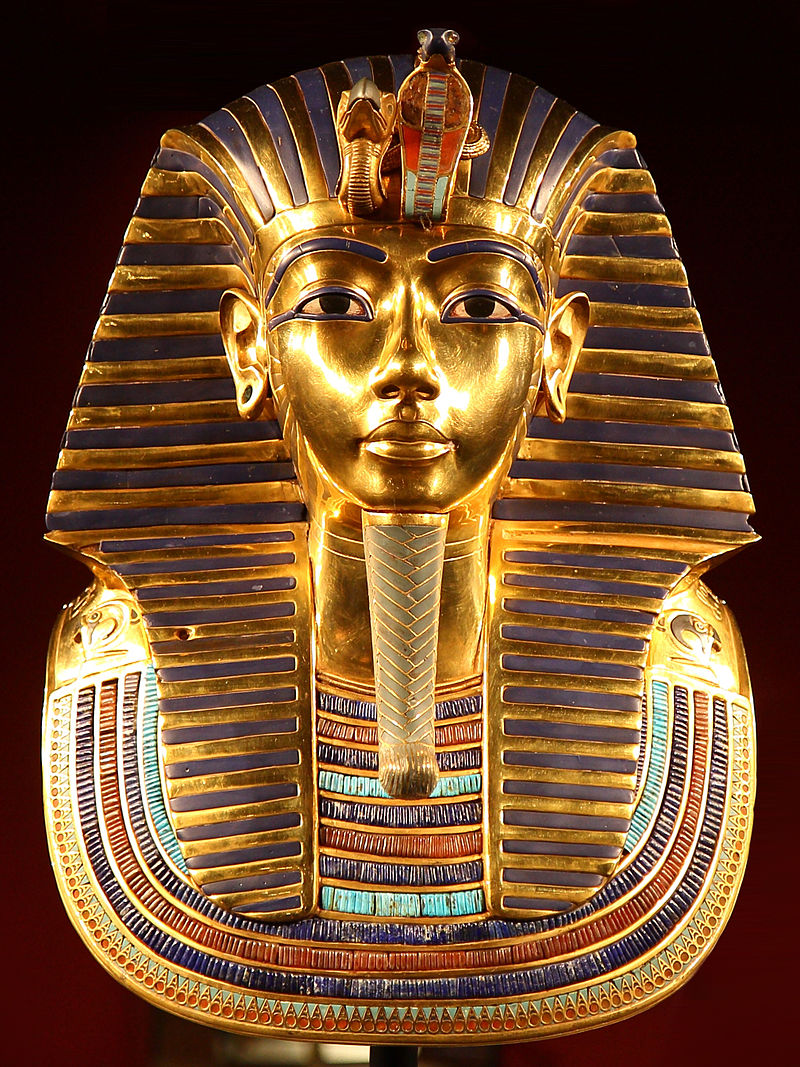

Also known as the Boy King, Tut became one of the most important figures of the ancient world and is still known as one of the most iconic people in history. A legend was that he was buried with his golden mask.

During the time when pharaohs ruled, the Valley of Kings was the burial place for all great rulers. It is now known to archaeologists as the New Kingdom, which is dated from 1550 to 1069 BC. Many discoveries have been made in the Valley of Kings and have helped dozens of archaeologists and historians learn about the time when pharaohs ruled.

Nearly 3,000 years after the last person was buried in the Valley, the site became famous in the 19th and 20th centuries. A map was made by Napoleon’s expedition there in the early 1800s, when he recorded the positions of 16 tombs. By World War I, the number had risen to 61 tombs discovered.

In 1914, an American lawyer named Theodore Davis was responsible for many more discoveries in the area. However, later that year, he dubbed the area to be “exhausted” of new discoveries. Carter did not believe Davis at all; he still believed there were tombs left undiscovered in the area. One of those tombs was King Tut’s.

Under the patronage of the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, Carter began excavations in the Valley in 1917. Carter dug for several unsuccessful seasons, testing Carnarvon’s patience season by season, until he made the greatest discovery of all time.

According to scholarly documents, Tut’s name did not appear on any king-lists. All historians knew was that Tut reigned into a ninth year. It was believed, and turned out to be correct, that he was the king of the Amarna period. Following the reign of his father, Akhenaten, Tut abandoned the traditional Egyptian polytheism and introduced the god Aten. He was also noted for reintroducing the worship of the god Amun. At some point he abandoned his original name Tutankhaten to become Tutankhamun.

By looking at a scattering of decorated blocks, historians were able to tell that Tut had been a builder, but his lifestyle and work remain a mystery. His tomb proved to be one of the most highly and beautifully decorated tombs found, but it did not lead the historians to find much new about the Boy King.

One thing that could be told of the king was how old he was when he died. Scientists and researchers looked at Tut’s mummified remains on four separate occasions. The first time was on November 11, 1925 as the body was examined by Carter and his team of forensic experts. One of those experts was Douglas Derry, who was an anatomist at the Government School of Medicine in Cairo.

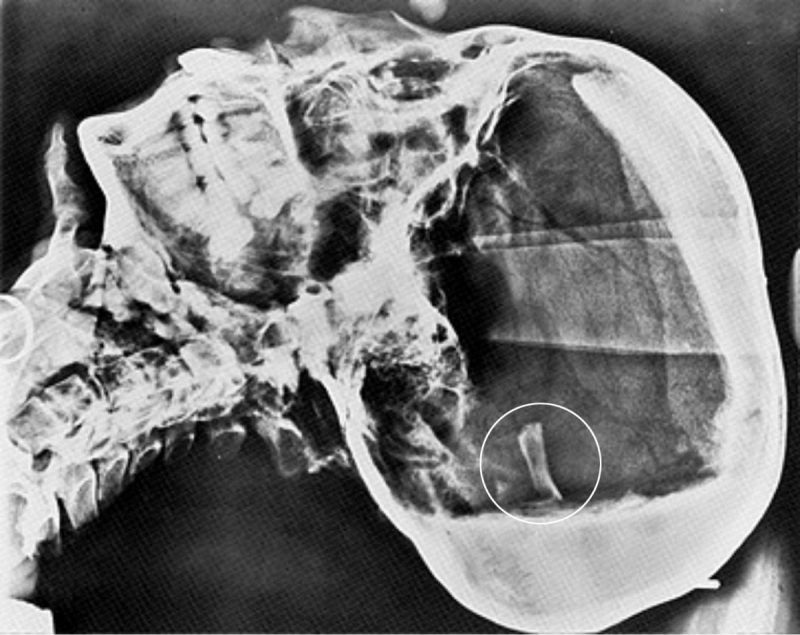

In 1968, a group from Liverpool University led by Ronald Harrison x-rayed the remains. This allowed the Egyptologists to carry out a more detailed study than previously. In 1978, Dr. James Harris had looked closer at Tut’s skull and teeth with new x-rays. Then in 2005, Dr. Zahi Hawass performed a CT scan of the remains, which provided the most detailed images of the body yet. All studies conducted conclude that Tut died between the ages of 17 and 19. However, that is all the researchers found out.

Different specialists have speculated on how Tut died and what conditions afflicted him during his life. Some believe that since inbreeding was common in royals it could have been general physical weakness that killed him. Other issues could have been pectus carinatum, also known as pigeon chest, or even Tutankhamun syndrome, which had symptoms like breast development, a sagging abdomen, and flat feet.

Other items found in the tomb like walking sticks led archaeologists to believe these could have been something Tut needed in order to move around. This possibility also came from the depictions of Akhenaten that show him as a deformed and grotesque figure, though nobody knows if Tut suffered from the same issues.

Out of the many speculations comes the one that King Tut could have met foul play. Many people have suggested it but haven’t really taken the time to prove the theory. During 1968, Harrison had looked at a small piece of bone that was detached from the skull. Harrison believed that Tut had suffered a blow to the head, which caused the king’s death. While some believe it could have been a terrible accident, others believe that the king could have been murdered. After the 2005 CT scan was done, many other researchers came to believe the skull bone fell off postmortem and had nothing to do with Tut’s death.

Dr. Hawass’s CT scan showed that Tut had suffered a fracture to his left femur. What makes the discovery most interesting is that a good amount of embalming fluid had entered the break, suggesting that the break was definitely there before death. This discovery suggests that there was no time for the wound to heal before Tut died, meaning that the break occurred the last few days before the king died. But the break alone was not the sole cause of death. Hawass suggested that the wound could have become infected, which would have contributed to his death.

To add to all of the mystery that surrounds the king, his body showed strange features around his torso. Several ribs and a section of his left pelvis were completely missing. The embalming incision was also in the wrong area. The soft tissue inside the chest cavity was removed and replaced with rolls of linen and the arms were crossed in an unusually low position. The heart was also missing, which was a major indication that something went wrong – the heart was meant to be left in the body because it was crucial for survival in the afterlife.

While some of these issues with the body could have been the result of the manner of Tut’s death, some researchers have taken in the possibility of Carter and his team having something to do with it. While excavating the tomb, the team could have bumped the body around a bit and caused some of those parts to break or go missing.

Carter’s journal entries that have been made public suggest that he and his team had major issues with freeing the tombs while excavating. There were two smaller coffins next to Tut’s larger one. Tut’s body was a tight fit around the smallest coffin and was stuck to the embalming oil which was poured over his body. Carter had tried everything to loosen up the oils but nothing worked, so Derry had to perform the autopsy with the mask still on the body.

Like many pharaoh burials, Tut was adorned with dozens of jewels, which made it difficult to remove the body from the oils. When the king was reinterred after Carter’s team was finished with it, the skull-cap and beaded necklace were left on the body. When Harrison came along in 1968, both items were missing. Harrison’s x-rays showed that there was damage to the thorax, and missing ribs which Derry hadn’t observed. This suggested that not only did the robbers remove the jewels, they also removed bones.

There could have been a number of reasons for that. They could have been removed before the burial. Some of the ribs were broken and some were cut smoothly and packed with linen underneath them. The way the cuts were made suggest that this was done before the body was packed. The bone was still healthy when it was cut, evidence of the injury having happened before death.

One Egyptologist believes Tut’s torso was damaged in a massive accident, which forced the embalmers to remove the ribs, heart, and other abnormal soft tissue in the mummification process.

There was damage solely to Tut’s left-hand side from the torso to the clavicle to the pelvis, as if a tall, blunt object did great damage. Many believe these injuries could have only been caused by a chariot accident.