The little Tennessee town, Oak Ridge with its 29,330 inhabitants holds a rather dark and “atomic history.” The city that is also known as the Secret City, the Ridge, The Atomic City and the City Behind the Fence emerged in 1942 as a production site for the Manhattan Project-the massive American, British, and Canadian operation that developed the atomic bomb.

In 1942, the United States federal government chose the area as a site for developing materials for the Manhattan Project. Maj. Gen.Leslie Groves, military head of the Manhattan Project, liked the area for several reasons. Its relatively low population made acquisition affordable, yet the area was accessible by both highway and rail, and utilities such as water and electricity were readily available due to the recent completion of Norris Dam. Finally, the project location was established within a 17-mile-long (27 km) valley. This feature was linear and partitioned by several ridges, providing natural protection against the spread of disasters at the four major industrial plants—so they wouldn’t blow up “like firecrackers on a string.”

When the Governor of Tennessee Prentice Cooper was officially handed by a junior officer (a lieutenant) the July 1943 presidential proclamation making Oak Ridge a military district not subject to state control, he tore it up and refused to see the MED District Engineer Lt-Col James C. Marshall. The new District Engineer Kenneth Nichols had to placate him. Cooper came to see the project (except for the production facilities under construction) on November 3, 1943; and he appreciated the bourbon-laced punch served (although Anderson County was “dry”). CEW and HEW accommodation in houses and dormitories was basic, with coal rather than oil or electric furnaces. But it was of a higher standard than Groves would have liked, and was better than at Los Alamos. Medical care was provided by Army doctors and hospitals, with civilians paying $2.50 per month ($5 for families) to the medical insurance fund.

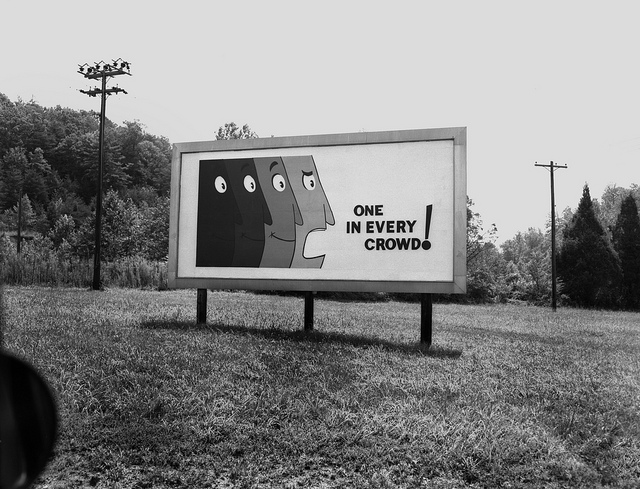

The location and low population also helped keep the town a secret, though the population of the settlement grew from about 3,000 in 1942 to about 75,000 by 1945. The K-25uranium-separating facility by itself covered 44 acres (18 ha) and was the largest building in the world at that time.The name “Oak Ridge” was chosen for the settlement in 1943 from among suggestions submitted by project employees. The name related to the settlement’s location along Black Oak Ridge, and officials thought the rural-sounding name “held outside curiosity to a minimum.”The name wasn’t formally adopted until 1949, and the site was referred to as the Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) until then. All workers wore badges. The town was surrounded by guard towers and a fence with seven gates.

By March 1943, the COE had removed the area’s earlier communities and established fences and checkpoints. Anderson County lost one-seventh of its land and $391,000 in annual property tax revenue. The manner by which the Oak Ridge area was acquired by the government created a tense, uneasy relationship between the Oak Ridge complex and the surrounding towns that lasted throughout the Manhattan Project. Although original residents of the area could be buried in existing cemeteries, every coffin was reportedly opened for inspection.

The Corps’ Manhattan Engineer District (MED) managed the acquisition and clearing. The K-25, S-50, and Y-12 plants were each built in Oak Ridge to separate the fissile isotope uranium-235 from natural uranium, which consists almost entirely of the isotope uranium-238. During construction of the magnets, which were required for the process that would separate the uranium at the Y-12 site, a shortage of copper forced the MED to borrow 14,700 tons of silver bullion from the United States Treasury to be used for electrical conductors for the electromagnet coils as a substitute. The X-10 site, now the location of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, was established as a pilot plant for production of plutonium using the Graphite Reactor.

Because of the large number of workers recruited to the area for the Manhattan Project, the Army planned a town for project workers at the eastern end of the valley. The time required for the project’s completion caused the Army to opt for a relatively permanent establishment rather than a camp of enormous size.

The architecture firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) was contracted to provide a layout for the town and house designs. SOM Partner John O. Merrill moved to Tennessee to take charge of designing the secret buildings at Oak Ridge. He directed the creation of a town, which soon had 300 miles (480 km) of roads, 55 miles (89 km) of railroad track, ten schools, seven theaters, 17 restaurants and cafeterias, and 13 supermarkets. A library with 9,400 books, a symphony orchestra, sporting facilities, church services for 17 denominations, and a Fuller Brush Company salesman served the new city and its 75,000 residents.No airport was built, however, for security reasons.Prefabricated modular homes, apartments, and dormitories, many made from cemesto (bonded cement and asbestos) panels, were quickly erected. Streets were laid out in the manner of a “planned community”.

The original streets included several main east-to-west roads, namely the Oak Ridge Turnpike, Tennessee Avenue, Pennsylvania Avenue, Hillside Road, Robertsville Road, and Outer Drive. North-to-south oriented streets connecting these main roads were designated “Avenues”, and streets branching off from the avenues were designated “Roads”, “Places”, “Lanes”, or “Circles”. “Roads” connected two streets, while “Lanes” and “Places” were dead ends. The names of the main avenues generally progressed alphabetically from east to west (e.g., Alabama Avenue in the east, Vermont Avenue in the west), and the names of the smaller streets began with the same letter as the main avenue from which they started (e.g., streets connected to Florida Avenue began with “F”). This made it considerably easier for the city’s new residents to find each other.

Housing for families was constructed according to a series of templates, identified by letters. Thus an “A” house was the smallest lettered design, with two small bedrooms and one bathroom. A “B” house featured two bedrooms, one bathroom and a larger living space. A “C” house featured three bedrooms and one bathroom. A “D” house featured three bedrooms with one and one-half bathrooms and a larger living space. An “E” was a two-story four-unit structure, and an “F” was the largest type home. The smallest homes were called “flat tops”; originally intended to be only temporary structures, they proliferated atop the ridges in the west end of town.

More spacious homes were awarded by the government based upon family size and the status of the worker.If a couple became divorced, they would usually be “demoted” in terms of their housing allocation, and a worker who became unemployed would usually lose his or her home altogether.

Construction personnel swelled the wartime population of Oak Ridge to as much as 70,000. That dramatic population increase, and the secret nature of the project, meant chronic shortages of housing and supplies during the war years. The town was administered by Turner Construction Company through a subsidiary named the Roane-Anderson Company. For most residents, however, their “landlord” was known as “MSI” (Management Services, Inc.).

The news of the use of the first atomic bomb against Japan on August 6, 1945, revealed to the people at Oak Ridge what they had been working on.

All photos by doe-oakridge.