In 1964, Donald R. Currey, a graduate student from the University of North Carolina, did something that would cause argument and discussion the world over.

Dendrochronologists (people who study rings of trees to determine the tree’s age), had been trying to find the oldest tree in the world from the 1950s onwards. So far, the Methuselah tree from the White Mountains in California had been thought to be the oldest of the non-clonal trees. That is until Prometheus was found; this was a type of bristlecone pine in the Great Basin National Park in Nevada.

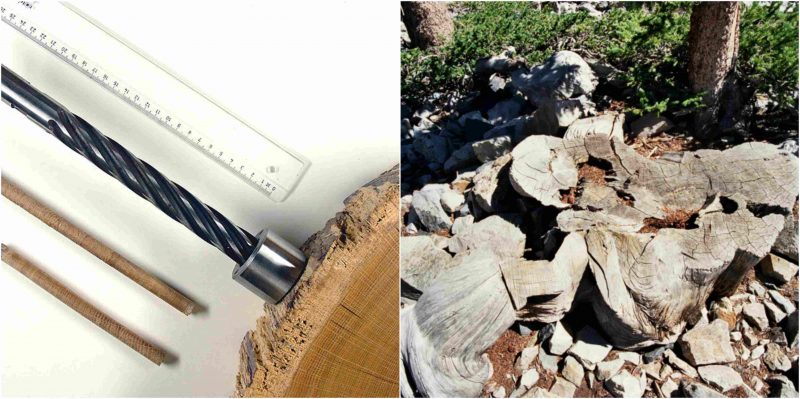

It is unclear whether Currey, who was researching the ‘Little Ice Age’ with the knowledge of the US Forest Service, was told to cut the tree down or if he did it on his own accord. When sectioned into pieces and then studied, the tree was found to be 4862 years old, and possibly even older than that. The pine is popularly known as Prometheus, but is recorded as WPN-114; it means that this was the 114th tree Currey had sampled in White Pine County. He didn’t cut down 114 trees; he cored them all except this tree. Coring is believed to not harm a tree – a special borer is used to create a pencil-thin tube of wood that can be studied. It is thought that Currey was unable to collect such a sample, so he had the tree cut down, thus destroying a valuable living specimen.

In his article in the journal Ecology, Curry says he sectioned the tree for two reasons – first, to study the rings, and second, to see if the oldest bristlecones were from the White Mountains in California only or if they could be found elsewhere. The loss of this great tree helped along the movement to protect such old trees; 22 years after the felling of Prometheus, the area became a national park.

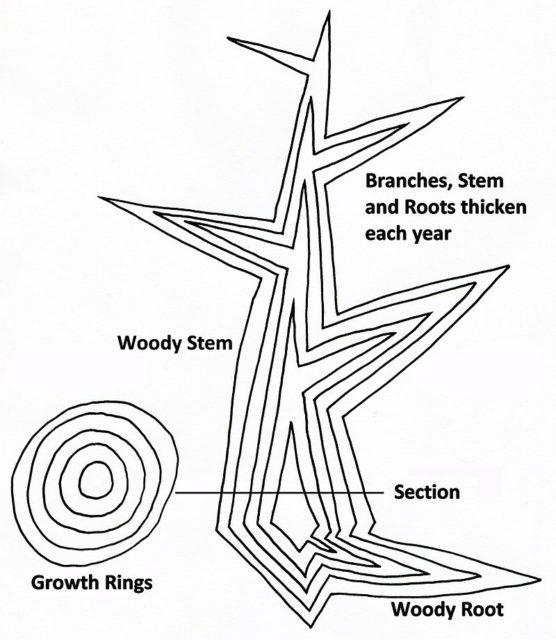

So why are tree rings and finding the oldest trees so important? Scientists use the age of the trees to help them track past climates, such as in the ‘Little Ice Age’, to answer their curiosity about how long-living organisms can live, and to help date archaeological ruins. Each ring, counted by taking a sample piece of the tree’s diameter, represents approximately a year of growth. Tree ring widths are variable; trees grow in predictable patterns as they respond to the changing seasons.

Scientists can tell if the year had a drought by comparing its rings, however, some trees have missing rings, and others can have multiple rings in a year, so the selection of trees for the study has become quite precise. Trees are often sampled in a cluster so that they can be compared to each other and a clearer idea of the climate can be seen. Computers now aid this science significantly.

Non-clonal trees are ones that have not cloned themselves from their underground root systems. The Quaking Aspen in Utah is a clonal tree that, while it looks like 47,000 individual trees, it is in reality just one that has sent up many shoots from its extensive root system.

Hazelnuts, poplars, and the blueberry are also clonal plants. Such trees as bristlecone and oak trees are non-clonal, having grown from individual seeds into a unique organism.