At the beginning of World War II, the Nazis sought to find ways to effectively disrupt the British economy. In September of 1939, the head of the central criminal investigation department of Nazi Germany, Arthur Nebe, proposed an extensive covert operation which would employ skilled counterfeiters to forge British pounds. A gargantuan amount of forged banknotes would be dropped over Britain, and, in Nebe’s opinion, this would cause an immediate economic collapse, the result of which would see the British pound lose its status as the world’s reserve currency.

Joseph Goebbels, the infamous Reich Minister of Propaganda, and Nebe’s superior, a high-ranking SS official named Reinhard Heydrich, thought that the plan might work, so they promptly presented it to Adolf Hitler himself. Although the Minister for Economic Affairs advised Hitler against the plan because it would breach international law, Hitler immediately approved the plan and Heydrich appointed SS Major Alfred Naujocks as the head of the counterfeiting operation, codenamed “Andreas.”

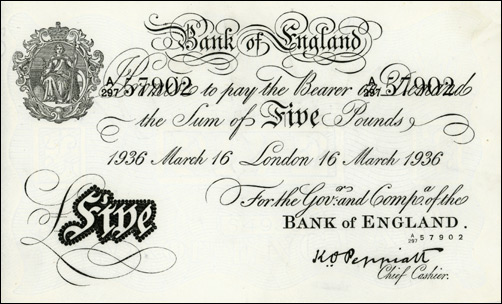

In January of 1940, Naujocks recruited a group of skilled counterfeiters and technical advisors and set up a forgery unit in Berlin. After seven months of intensive work, the unit managed to produce a virtually indistinguishable forgery copy of the five-pound banknote. They broke the code of the British serial numbering system and produced banknotes with valid serial numbers. They also replicated the rag paper used by the British and duplicated the chemical balance of British water in order to match the exact shades of the British paper and ink. The biggest challenge for the unit was to reproduce a vignette of Britannia in the top left corner of the five-pound note: Counterfeiters nicknamed it “Bloody Britannia” because it was extremely difficult to reproduce.

By early 1942, the unit had produced between £500,000 and £3,000,000 in flawless counterfeit banknotes.

Fortunately for the British economy, the Nazis never dropped any of the money over Britain. The unit was decommissioned in early 1942 after Naujocks fell out with Heydrich, and the money was never used. Also, British spies had uncovered classified details of Operation Andreas and alerted the Bank of England as well as the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Out of caution, the Bank of England stopped producing new five pound notes, released a special version of the one pound note which had a metal security thread running through the paper, and banned the import of any pound notes from anywhere in the world.

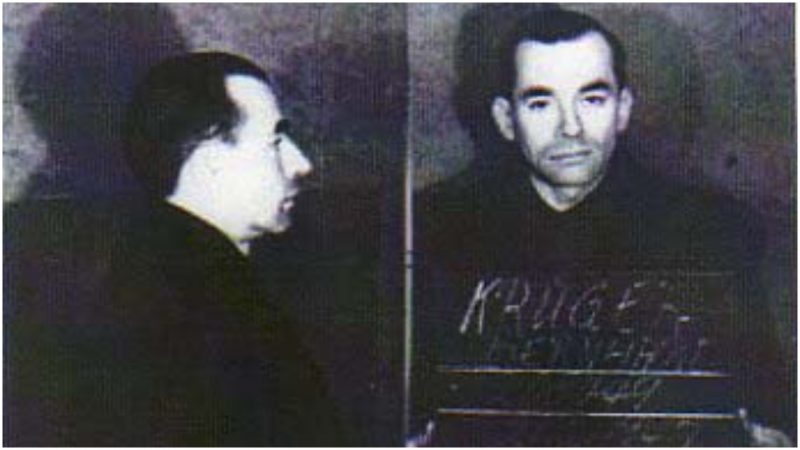

In July of 1942, the operation was revived by Heinrich Himmler, who appointed SS Major Bernhard Krüger as the new mastermind of counterfeiting. The operation had a new goal: The Nazis no longer wanted to drop the counterfeit money on England, but to use the money to finance the covert operations of the German intelligence divisions. Also, Krüger was ordered to employ Jewish prisoners incarcerated in Nazi concentration camps. He assembled a group of over 100 Jewish experts and set up his unit at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Krüger supplied the prisoners with equipment and provided them with cigarettes, newspapers, books, and a radio. Many of them were escaping near-certain death by being involved in the operation. From mid-1943 to mid-1944 the unit produced a staggering amount of 65,000 counterfeit banknotes per month. The money was used to finance the secret operations of German spies throughout the world, and around £100,000 counterfeit pounds were used to gather the information that helped to free the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in the Gran Sasso raid in September of 1943.

In 1944, the unit was ordered to forge the U.S. dollar. However, the artwork of dollar banknotes was much more complex than that of the pound. On top of that, the U.S. serial numbering system was far different than the one used by the British, and the prisoners had trouble deciphering it. Furthermore, the prisoners realized that the creation of a flawless forgery of the $100 bill would be dangerous for their lives because they would likely be executed afterward, so they slowed their progress as much as they could. Only around 20 complete $100 banknotes were produced by January of 1945.

In early March of 1945, with the advance of the Allied forces, the unit was transferred to the concentration camp of Mauthausen-Gusen in Austria. In order to destroy the evidence of the covert operation, the prisoners were ordered to destroy all remaining counterfeit banknotes.

Read another story from us: Swimming in searchlights: The cathedral of light of the Nazi rallies

The majority of the money, along with the equipment, was dropped into the nearby lakes Toplitz and Grundlsee. Although no serious harm had been done to the British economy, enough counterfeit pound notes had gone into general circulation that the Bank of England changed the design of the notes after the war.